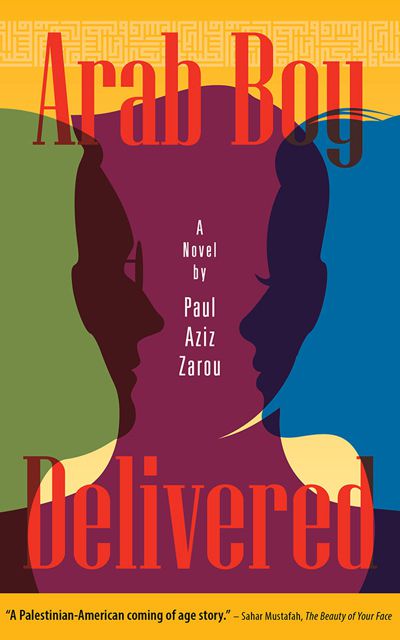

Michael Haddad, the teenage son of Palestinian immigrants, comes of age during the tumultuous sixties in his family’s neighborhood grocery store in New York City.

In 1967 Michael maneuvers through the working-class neighborhood delivering groceries and enters the homes and lives of his customers. He’s confronted by the violence of racist bullies and falls for the radical college coed who teaches him about sex, love, and protest. Michael grieves with the mother whose only son died in the Vietnam War and is embraced by the first black couple who move into the neighborhood. They all shape him, and through the conflict of hate, acts of kindness, and his sexual awakening, Michael struggles to figure out who this dutiful son of an immigrant family is.

Michael’s life is buffeted by the killing of Martin Luther King, Jr, and the death, two months later, of Bobby Kennedy. His girlfriend opens his eyes to the ongoing struggle to test national ideals against the growing diversity of America. But when Michael experiences a sudden personal tragedy, he must learn to get past his fears, come to terms with his heritage, and set himself free.

Chapter One

It was a brick, still layered with the pitted crust of mortar and chipped on one corner. Thrown with reckless anger, the brick hit dead center, collaps-ing the grocery’s large picture window. The shattering glass startled Michael awake some time after 2:00 am. He had been in the middle of a dream, which allowed him to imagine—if for only a couple of fleeting seconds—that he was still back in the comfort of his old bedroom in Brooklyn. Michael’s torso tensed and he jerked upright. A sour knot formed in the pit of his stomach at the disquieting realization that the crash that had woken him was the storefront window—the window directly beneath his bedroom. Michael heard muffled hoots and shouts, followed by the sound of skidding tires as a car sped away.

During an oppressive mid-June heat wave, and a week after the Six-Day War, Michael’s father had taken ownership of the grocery in Queens Village and moved his family from their Brooklyn neighborhood, where their native Arabic was spoken and everyone was in some way related to each other—if not by blood, then by heritage and community. Palestine, the country that Michael’s parents had emigrated from several years before his birth, was now occupied. And in his upstairs apartment bedroom, Michael was just starting to get comfortable in his new surroundings—just beginning to learn how to sleep again.

Michael’s father, thick black hair disheveled, jumped out of bed and into his pants and flew down the stairs. Michael trailed after him, but as he took his first step out of their apartment door, his mother—who had hesitated at first—grabbed his arm for balance. As they carefully navigated the narrow staircase, her firm grip tugged on Michael, slowing him, holding him back, as if she didn’t want to let him go.

Michael’s mother had never spoken about her reluctance to embrace what her husband considered his stake in their future. But Michael, an only child, intuitively knew his mother’s emotional undercurrents. He often understood his mother’s position on things not by what she said, which was very little on most topics, but by the subtle shades of quiet she slipped into. By measuring the depth and weight of her introspection, he would know when to be concerned.

When his father had announced his purchase of the store, Michael felt her unspoken reluctance by her immediate retreat. But he couldn’t discern whether it stemmed from general caution or regret over their savings being sunk into a new business. Perhaps she had received an unsolicited warning from her aunt who read prognostications from the intricate swirls at the bottom of her Arabic coffee cup—which Michael believed his mother wouldn’t heed anyway. But as time progressed, whatever it was that was causing her reticence seemed to dis- solve, and she moved forward with a renewed acceptance. After all, how could she argue with a husband whose goal was to better their lives?

Michael had forgotten her initial reaction until this moment. As they neared the bottom of the stairs, he turned to look up at her. Her eyes widened and she gave him a slight nod, her best effort at reassuring him. But her small hand nervously clutched his arm, speaking to the contrary. She remained stoic so as not to betray how she really felt. But at fifteen, her son knew better.

The Schaefer light, which hung in the window by two thin wires, was still swinging, unbroken by the impact. The shattered window, jagged edges glis- tening under the swaying of the fluorescent light, reinforced Michael’s sense of exposure. He stood frozen, staring at the black gaping hole, until his father called out, “Come help.”

While Michael busied himself sweeping up shards of glass from behind the counter, he spotted a large piece wedged under the worn butcher block that held the cash register. He knelt down awkwardly, and as he stretched an unsteady hand out to reach for it, he caught the sharp edge and sliced his index finger open. Blood oozed to the surface in a thick line that defined the length of the gash. As he stood up and moved his hand to examine the damage, a bright red drop spilled onto the floor and was swallowed up by the porous wood. Michael stuck his finger in his mouth the warm blood tasted sweet as he gently wrapped his tongue around the cut. And as he took that moment to nurse his finger, his nerves let go and he suddenly felt tired, faint. This feeling lasted as long as it took for his mother to splash alcohol over the cut and examine it for slivers of glass.

The 1967 Plymouth police cruiser eased up to the curb across from Haddad’s Grocery as if stopping for a routine dinner break. Sergeant Neal McClusky stepped out of the patrol car, followed by a young rookie officer, Phillip Bosco, who lagged several steps behind. McClusky walked right in, but Phillip stayed outside and surveyed the broken window and then, with the beam of his flashlight leading the way, walked the perimeter of the building. When Phillip returned, he hung back and studied the family as intently as he had the broken window.

“Do you have any idea who’d do something like this?” Sergeant McClusky asked.

In his mid-thirties, Sergeant McClusky was fit and had tight, pasty skin that appeared translucent over his sharp features, features that reflected his earnest professional demeanor.

“No,” Mr Haddad said.

McClusky shook his head. “It’s unusual. Not something that happens here.

It’s a good neighborhood.” “What does that mean?”

McClusky, caught a little off guard by the pointed response, stammered a bit and then said, “Uh . . . it’s probably just some kids horsing around.”

Mr Haddad didn’t appreciate the vandalism to his store being dismissed as “horsing around,” but just shook his head.

“We’ll keep an eye out,” McClusky assured him.

As if suddenly remembering something that he should not have forgotten, Mr. Haddad asked, “Can I get you coffee? From upstairs?” He gestured toward the deli case. “Or a sandwich?”

They politely, and somewhat awkwardly, declined both offers. “It’s no trouble.”

Phillip stepped up to the counter. “Can I get a pack of Winstons?” he asked, digging into his uniform pocket to fish out the 39 cents.

Mr Haddad handed him the cigarettes and then waved him off. “It’s okay.” “You sure?” Phillip asked with exaggerated earnestness, trying to assuage an immediate pang of regret. Maybe he shouldn’t have asked for the cigarettes.

He’d become accustomed to businesses readily handing over a pack of cigarettes or a sandwich or coffee and refusing payment, but he lived in this neighborhood. It was his home. And these were new owners. Despite being in uniform, on official business, walking into this store reminded him of the countless times he’d been there to pick up groceries for his mother. Somehow it didn’t feel right to accept Mr Haddad’s gesture, or at least as comfortable as it had with the others.

“Yes. Please, take the cigarettes,” Mr. Haddad insisted, nodding reassuringly. Phillip, still uncertain, held his hand out for a bit longer, cupping the change. Then he slowly stuck his hand back into his pocket and felt the change slip through his fingers and settle at the bottom, next to his extra handcuff key.

“Thanks.”

McClusky was jotting down some notes on a small pad, and without look- ing up he asked, “Haddad, would you spell your first name for me?”

“Aziz, A-Z-I-Z.”

“Got it.” McClusky flipped his pad closed and assured Aziz once again that they’d keep an eye out.

Michael watched as the two officers drove away with more haste than they’d arrived with. Then Michael and his father found a couple of sheets of plywood in the basement and boarded up the window.

Back in his small bedroom, Michael sat down hard on his bed, feeling an uncharacteristic weariness in his young body. He surveyed his small room through the haze of yellow light cast by an old gooseneck lamp on his night- stand. It crossed his mind that maybe he should get up and brush his teeth, but he decided that since he hadn’t eaten anything while they were downstairs cleaning up—the few drops of blood from his finger didn’t count—and since he had brushed before he went to bed the first time, he didn’t need to. Sleep wasn’t possible, so Michael reached under his bed and slid out a small card- board box he still hadn’t finished unpacking. He sifted through the various books and keepsakes until he found his worn copy of Casino Royale. Michael wished to escape into the world of clear-cut bad guys and a cool good guy who always wins—and beautiful women, of course. But despite his infatuation with James Bond, the words written on the page were out of focus. After rereading the same page three times, he gave up, shut off the light, and just lay there staring at the murky shadows splashed on his gray ceiling until fatigue carried him past the throbbing in his finger and the gnawing in his stomach and he drifted into a fitful sleep.

Aziz Haddad’s face was outlined by the dim amber glow of his burning cigarette

as he sat in his car, watching over the store for hours into the night. Despite his vigilance, it had happened again. And again. And Michael had received his share of splinters from the plywood they’d used in the late morning hours to secure the broken windows.

Michael’s anxiety tempered a little each time they had to clean up glass, and he wasn’t sure why this was. Did each subsequent violation make it easier? Maybe he’d grown used to the routine or maybe, at least for the moment, pick- ing up some broken glass was the worst of it.

After the third incident, whoever was breaking their windows finally grew bored and stopped. But for Michael what remained was an underlying fore- boding, which would fade with time but never completely leave. Michael had accepted that their lives had changed, but he couldn’t foresee the extent to which their lives would become entangled in their new store and the surround- ing neighborhood. Michael wanted to believe as his father did, that it was all for the better. But whenever he thought about that night, he could still feel his mother’s anxious grip squeezing his arm.

Amazon.com: https://www.amazon.com/Arab-Delivered-Paul-Aziz-Zarou/dp/1951082397

Meet Paul Aziz Zarou

Paul Aziz Zarou: Writer and Business Professional. An Arab-American born and raised in New York by Christian Palestinian immigrants, Paul moved to Los Angeles early in his working life. He raised his family in LA and now lives here with his wife. Pau’s love of literature, history, and politics is what motivates him to tell stories. As a writer of novels and screenplays, Paul enjoys exploring both the social and political landscapes of the past and the timeless complexities of family dynamics.

Connect with Paul

Website: www.paulzarou.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pzarou

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/paulzarou/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/pzarou

Sounds like an interesting story and an excellent writing style. I might just have to check it out! Thanks for sharing!