Sixteen-year-old Jasmine Barrington hates everything about living in Kenya and longs to return to the island of Penang in British colonial Malaya where she was born. Expulsion from her Nairobi convent school offers a welcome escape – the chance to stay with her parents’ friends, Mary and Reggie Hyde-Underwood on their Penang rubber estate.

But this is 1948 and communist insurgents are embarking on a reign of terror in what becomes the Malayan Emergency. Jasmine goes through testing experiences – confronting heartache, a shocking past secret and danger. Throughout it all, the one constant in her life is her passion for painting.

From the international best-selling and award-winning author of The Pearl of Penang, this is a dramatic coming of age story, set against the backdrop of a tropical paradise torn apart by civil war.

THE FORGOTTEN CIVIL WAR

The historical inspiration for A Painter in Penang came from my growing awareness of what happened in Malaysia (then known as Malaya) after World War 2. I had written about the country before the war in The Pearl of Penang and during it in Prisoner from Penang so decided to set this book a few years after the war ended. I had little or no knowledge of the conflict known as The Malayan Emergency as it ended when I was a small child. It came as a surprise to me to discover it lasted twelve years between 1948 and 1960 – with a further insurgency between 1967 and 1989 despite Malaysian independence from Britain being in place since 1957.

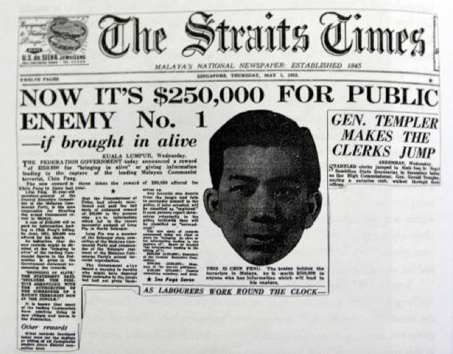

The leader of the communist insurgents was a man named Chin Peng, a Chinese Malay. Awarded the Order of the British Empire by the British for his bravery in fighting the Japanese, he turned from friend to enemy after the war, convinced that Malaya should become a communist state under the influence of Communist China. Chin Peng died in exile in Thailand in 2013 aged 88. He spoke in 1994 on a BBC documentary and made this admission, in hindsight:

“The mistake is that though we live in Malaya, we didn’t understand the real situation in Malaya.”

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, a number of mainly Chinese Malays, including the young Chin Peng, took to the depths of the jungle which runs the entire length of the Malay peninsula from the Thai border to the island of Singapore. There they formed the Malayan People’s Anti- Japanese Army, or MPAJA. They were supplied with airdropped arms by the British, and a small team of British Special Ops soldiers and volunteers, Force 136, joined them in the jungle to conduct guerrilla-style operations behind the Japanese lines. When the war ended and the Japanese surrendered, the MPAJA soldiers were told to hand over the large cache of arms they had been supplied with, and each would be paid £300 to help them resume life as private citizens. Chin Peng was given his OBE in a ceremony in London. Little did anyone know then, that this man would soon unleash a twelve-year reign of terror on British Malaya that would outlast independence and make him Britain’s Most Wanted.

After the war, the former MPAJA members rightly expected that they would be given rights of citizenship, including voting rights, in the first step towards Malaya’s independence from Britain. Things didn’t work out that way though. Malaya, although a British holding, had always had a mixed political system with federal states being ruled by fabulously wealthy sultans – such as those of Johore and Selangor. These were the titular heads, although each had a British appointed administrator who influenced the executive decisions – the British maintained a tight grip. Yet for the Malay people, the sultans were a visible symbol of their rightful ownership of the country. The sultans were fiercely protective of the indigenous culture and heritage and resented the Chinese Malays – who were now close to half the population. A deal was done between the sultans and the British, denying equal rights to the Chinese population. As you can imagine, this did not go down well with the likes of Chin Peng, who believed the cause of the Japanese defeat was down to them and their bravery. As the vast bulk of the weapons dropped into the jungle were still there – buried in secret caches – it was only a matter of time before the former MPAJA morphed into a new group of communist insurgents: the Malayan Peoples Liberation Army. Denied the ballot box, they took to encouraging strikes and walkouts in an attempt to cripple the recovering British rubber and tin industries. When that failed, they turned to civil war. The first step in a long and bloody struggle was the killing of three British rubber planters on the morning of 16th June 1948.

The deaths of the three British men, shot in cold blood with Tommy guns, shocked the entire country – as well as people in the UK. British rubber planters were seen by the communists as the tangible symbols of British colonial rule and killing them was a clear-cut indication of intent on Chin Peng’s part.

The Malayan Emergency, while initiated by a relatively small army of around six thousand communist insurgents, soon embroiled the entire country. While Chin Peng’s gripe was with the British, it didn’t stop the communists from murdering their fellow Chinese, and Malays, including women and children, often in the most brutal circumstances – in order to force their cooperation in supplying food and cash to the rebels. There were also atrocities on the British side, including the notorious Batang Kali massacre when twenty-four unarmed villagers were killed – still a source of controversy today. The bulk of the Malayan population were caught in the middle, often forced to support the communists or risk their lives.

The communist terrorists’ greatest ally was the jungle that ran the length of the peninsula. It was all too easy for them to melt back into its impenetrable depths, safely out of reach of the British, Commonwealth and Malayan military and police forces. As the conflict escalated, thousands of young British men, straight out of school, were conscripted into national service (compulsory between 1948 and 1960) and sent out to Malaya to help bring an end to the conflict. Many had never left Britain before and had to quickly adapt to intense heat and humidity and a hostile jungle – the domain of wild animals, insects and snakes, swamps, deep rivers and the ubiquitous blood-sucking leeches which got everywhere – particularly into boots and underpants.

But this was not a war of bombings and battlefields. It could only be won through hearts and minds and hence propaganda played a huge role – as did the resettlement of numerous villages away from the hinterland of the jungle to areas where the communists found it more difficult to reach and influence the people. For their part, the communists relied on the min yuen – local people coerced or volunteering to support their cause by supplying food. Cleverly, the British introduced a system of identity cards for the whole population, knowing the terrorists would never come forward to claim theirs and hence anyone without ID being immediately suspected of being a terrorist. Chin Peng was immediately wise to that and sent his men out to hijack buses and trains and collect up ID cards and destroy them.

The Emergency lasted until July 1960, claiming around ten thousand lives on all sides including civilians and, in a road ambush, the British High Commissioner. In many ways it was a precursor to the Vietnam War – sadly many lessons that could have been learnt from it were ignored by the US military. Today, as a conflict, it is all but forgotten. The reason it was declared an Emergency and not a civil war was to protect the interests of the rubber planters and others – insurance was invalidated by war. So too, it protected those members of the military who might otherwise have been indicted for war crimes – for example the scandal that horrified Britain when a photograph of a soldier holding the decapitated heads of two Malayan suspected communists, one a woman, was printed in the newspapers.

A Painter in Penang attempts to show how many innocent people got sucked into the conflict. I chose a sixteen-year-old British girl as my main character – the eponymous painter. Jasmine Barrington was born in Malaya and now returns, escaping her miserable time at school in Africa. The Emergency is seen through her (often naive) eyes, those of her hosts the owners of a rubber plantation, her friend Howard, a young planter close to the action on the peninsula, a British soldier, and indigenous Malayans, notably Bintang, whom Jasmine befriends. I don’t want to give away any spoilers but her stay in Penang is a dramatic coming of age for Jasmine and she ends the book more worldly wise than she started.

Similarly, the Emergency was the coming of age for the country that is now Malaysia – breaking free from colonialism, dealing with ethnic conflict and beginning a new future as a country in control of its own destiny.

Buy Link: Amazon

Meet Clare Flynn

Clare Flynn is the author of twelve historical novels and a collection of short stories. A former International Marketing Director and strategic management consultant, she is now a full-time writer.

Having lived and worked in London, Paris, Brussels, Milan and Sydney, home is now on the coast, in Sussex, England, where she can watch the sea from her windows. An avid traveller, her books are often set in exotic locations.

Clare is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a member of The Society of Authors, Novelists Inc (NINC), ALLi, the Historical Novel Society and the Romantic Novelists Association, where she serves on the committee as the Member Services Officer. When not writing, she loves to read, quilt, paint and play the piano. She continues to travel as widely and as far as possible all over the world.

Connect with Clare

Website: https://clareflynn.co.uk

Blog: https://clareflynn.co.uk/alternate-blog-style-page.html

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/authorclareflynn

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/clarefly

Twitter: https://twitter.com/clarefly

Such an interesting post.

Thank you so much for hosting today’s blog tour stop.

Thanks, Mary Anne. It was a pleasure to write it and thanks to Mercedes Rochelle for hosting me!