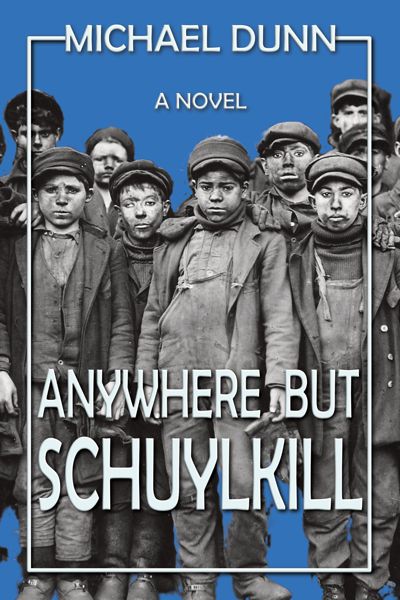

In 1877, twenty Irish coal miners hanged for a terrorist conspiracy that never occurred. Anywhere But Schuylkill is the story of one who escaped, Mike Doyle, a teenager trying to keep his family alive during the worst depression the nation has ever faced. Banks and railroads are going under. Children are dying of hunger. The Reading Railroad has slashed wages and hired Pinkerton spies to infiltrate the miners’ union. And there is a sectarian war between rival gangs. But none of this compares with the threat at home.

The Molly Maguires

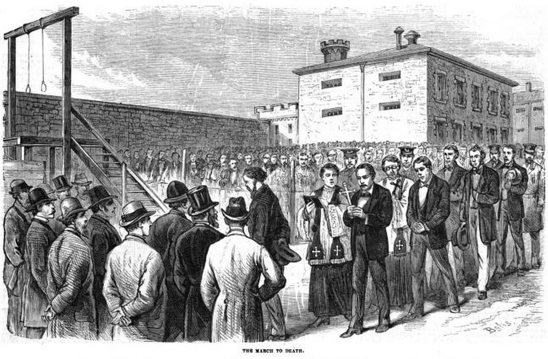

On June 21, 1877, ten Irish miners were hanged in a single day in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Known as Black Thursday, or Day of the Rope, it was the second largest mass execution in U.S. history (the largest being the execution of 38 Dakota warriors by the U.S. government in 1862). The Irishmen were convicted of murder, accused of being terrorists from a secret organization called the Molly Maguires. Ten more were executed over the next two years. Another twenty suspected Molly Maguires were imprisoned. Most were union activists. Some even held public office, as sheriffs and school board members.

However, there is no evidence that an organization called the Molly Maguires ever existed in the U.S. The only serious evidence against the men was presented by a spy, James McParland, working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency, who provided the plans and weapons the men purportedly used in their crimes. The entire legal process was a travesty: a private corporation (the Reading Railroad) set up the investigation through a private police force (the Pinkerton Detective Agency) and prosecuted them with their own company attorneys. No jurors were Irish, though several were recent German immigrants who had trouble understanding the proceedings. And nearly everything people “know” today about the Molly Maguires comes from Allan Pinkerton’s own work of fiction, The Molly Maguires and the Detectives (1877), which he marketed as nonfiction. His heavily biased book was the primary source for dozens of academic works, and for several pieces of fiction, including Arthur Conan Doyle’s final Sherlock Holmes novel, Valley of Fear (1915), and the 1970 Sean Connery film, Molly Maguires.

So, where did the myth of the Molly Maguires come from?

According to legend, there was a widow living in Ireland in the 1840s named Molly Maguire, who hated the landlords who were abusing the poor tenant farmers. She supposedly carried a pistol strapped to each thigh and she, or her followers, would beat or murder the tyrannical landlords, their agents, and bailiffs, whenever they tried to evict a tenant. No one knows if she ever really existed, but other tenant farmer activists were said to cry out, “Take that from a son of Molly Maguire!” when protesting against unscrupulous landlords.

Prior to this, there had been a long tradition in Ireland of people resisting oppressive policies, like the enclosure of their communal lands by wealthy landlords, exorbitant tithes collected by the church, high rent and evictions by absentee landlords, and sectarian violence by their neighbors. Over the centuries, those in power gave these activists names like Whiteboys, Levellers, Ribbonmen, and, by the early 1800s, Molly Maguires. It was believed that these groups organized themselves into regional lodges, and had a variety of secret greetings and oaths to ensure loyalty and solidarity among members.

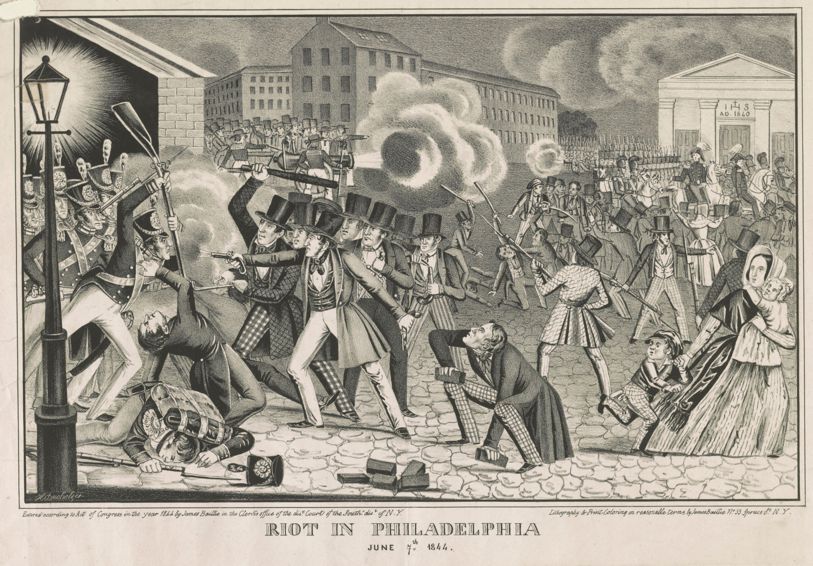

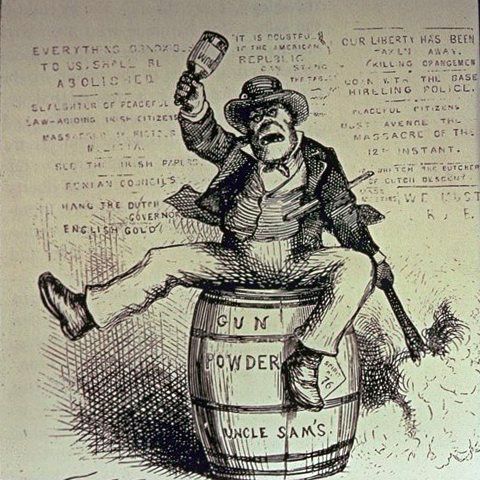

In 1845, millions of Irish fled the famine, the majority coming to the U.S. Nearly half of all U.S. immigrants in the 1840s were Irish. The racism against them was phenomenal. There were the No Irish Need Apply signs outside businesses looking for workers. There were pogroms in Irish communities carried out by anti-Irish nativist gangs, like New York’s Bowery Boys, and Baltimore’s Plug Uglies, gangs that were often affiliated with political parties like the No Nothings and the Republicans. There were also Irish gangs, often created for self-defense, at least initially, that were sometimes affiliated with the Democratic Party. At least twenty people died in anti-Irish riots in Philadelphia in 1844.

In the 1860s-1870s, there was considerable violence in Pennsylvania’s coal country, much of it blamed on the Molly Maguires. In Schuylkill County, alone, there were fifty unsolved murders just in the period of 1863 to 1867. But many of the victims were Irish, suggesting that at least some of the violence was sectarian and carried out by non-Irish ethnic groups. And many of the victims were union activists, suggesting that some of the violence was coming from the mine owners’ hired thugs. There was also a Welsh gang, known as the Modocs, who were affiliated with the local Republican Party and who served as their enforcers during elections. Considerable violence, as well as some murders, have been blamed on them. The Modocs frequently clashed with Irish residents, especially those affiliated with the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), a legal and state-recognized fraternal organization that had ties with the local Democratic Party. (The etymology of the Modoc name is obscure. Some believe they named themselves after the California/Oregon indigenous tribe. Others believe it comes from the legend of Madoc, a Welsh prince who supposedly came to America in 1170 and married an Indian princess.)

Sectarian violence was stoked by the mine owners, who would pit the different ethnic groups against each other. Indeed, the very structure of their workforce was designed to encourage ethnic mistrust and sow division. At the top of the hierarchy, and the pay scale, were superintendents and foremen, usually native-born, or English immigrants. They had the power to fire and blacklist workers, and some of the region’s violence was in retaliation for this. Next came the contract miners, generally Welsh and German immigrants. The lowest paid workers, who were mostly Irish, were the laborers. The owners could sometimes break strikes by offering the contract miners a small raise, thus enraging the laborers, who felt like they had been sold out. The owners also liked to hire Welsh miners, particularly Modocs, to moonlight as Coal and Iron Police (C&I), to harass and bully Irish labor organizers. (The C&I were created by the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1865 and operated without state oversight.)

The first known use of the term Molly Maguires in the U.S. was an October 3, 1857 article by Benjamin Bannan, in his Miners Journal newspaper, accusing them of election fraud. Bannan was a Republican, and an anti-Catholic nativist, who feared the growing political influence of the Irish newcomers to Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, who tended to vote Democratic. For years he had been blaming the Irish for the election of pro-slavery Democrats. He regularly used his paper to warn of the “Catholic threat,” and attack the Irish for their “drunkenness, laziness, and ignorance.” And from 1857 onward, his paper led the battle cry against the Molly Maguires. Bannan was also rabidly anti-union, and wrote hysterically about all forms of worker protest. In 1835, for example, he described a boat workers strike, in which workers threw rotten eggs at strikebreakers, as a “reign of terror.” He repeatedly accused the miners’ union, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA), of being controlled by Molly Maguires. Yet, the first Schuylkill County murders he blamed on the Mollies occurred during anti-draft protests of 1862 and 1863, whereas the WBA wasn’t even created until 1868. And much of the violence in that period was directed at mine superintendents and foremen, suggesting that it was rooted in grievances over pay and working conditions. But blaming a secret society of crazed, slavery-loving Irishmen was a convenient way to deflect public criticism of the mine owners, with whom Bannan was aligned.

The most violent period in Schuylkill County, however, occurred after 1873, when Franklin Gowen, president of the Reading Railroad (which owned the majority of the collieries), hired the Pinkertons to destroy the WBA. He claimed that Molly Maguires controlled the union, using the AOH as a front. The Pinkertons initially found no evidence of Maguirism in the union or the AOH. So, their agent, James McParland, infiltrated the AOH and encouraged its members to murder Modocs, as well as mine superintendents and foremen. This led to a sectarian tit-for-tat battle that worsened during the Big Strike (1873), and the Long Strike (1875), when the colliery owners used the C&I and the Modocs to attack Irish union activists. The most notorious of these attacks was the 1875 murder of Ed Coyle, a gifted WBA organizer and AOH member.

In 1875, Allan Pinkerton called for vigilante actions against Irish miners he accused of being Molly Maguires. Benjamin Bannan, of the Miners Journal, and Thomas Foster, of the Shenandoah Herald, used their papers to call for vigilante violence against the Mollies. On December 10, 1875, thirty masked men, heavily armed, broke into the Wiggans Patch (Mahanoy City) home of Ellen O’Donnell, shooting and beating residents. They killed 18-year-old Ellen McAllister, who was pregnant, as well as Charles O’Donnell. The Pinkertons denied any connection, but McParland, who was outraged that an innocent woman was killed, said the raid wouldn’t have been possible if someone hadn’t leaked his intelligence to the vigilantes. As for the O’Donnells, he said, “I am satisfied they got their just deserving.” One man, Frank Wenrich, a first lieutenant with the Pennsylvania National Guard and a former mayor of Mahanoy City, was arrested as the leader of the vigilantes, but he was released.

By the end of 1875, the Long Strike had been crushed and the WBA defeated. And in January, 1876, the Molly Maguire trials began. The first trial was for the murder of a Welsh mine foreman named John P. Jones. One of the suspects, Jimmy Powder Keg Kerrigan, turned state’s witness, pinning the murder entirely on his two co-defendants, Michael Doyle and Edward Kelly, both union leaders. However, Kerrigan’s wife testified that her husband committed the murder. She also refused to bring clean clothes to him in jail because he had blamed innocent men for his crime. There was speculation that Kerrigan was getting special treatment because his sister in-law was engaged to marry McParland. In the end, Kerrigan walked away, free, and the others were executed.

Several other murder convictions were obtained based solely, or predominantly, on the testimony of McParland. Several other convictions were obtained entirely on his claim that the defendants had secretly confessed to him. In one case, an eye witness testified that he clearly saw the murderer of Thomas Sanger and William Uren, and that the defendant, Thomas Munley, was not him. Yet Munley was still convicted on the basis of McParland’s claim of a secret confession and, ultimately, executed. Another Molly who was charged with murder, Kelly the Bum, supposedly said, “I’d squeal on Jesus Christ to get out of here.” In exchange for his testimony, his murder charge was dropped. Tavern owner Muff Lawler, also charged with the Sanger-Uren murders, turned state’s witness, as well, and got his charges dropped.

Muff is portrayed in my recent novel, Anywhere But Schuylkill. He was a union leader who served on the WBA bargaining committee during the Big Strike. He also attended the Anti-Monopoly meeting in Harrisburg, in 1873, and may have been involved in the early organizing of the Greenback Party. He later opened a tavern and raised game cocks. His nickname comes from his favorite breed, the muff. From what I could gather, he was charismatic and probably mentored many younger union members. He also had a large family, with several very young children, and this likely influenced his decision to betray his comrades.

The following is the first stanza from the song-poem, Muff the Squealer, composed by Poet Mulhall:

When Muff Lawler was in jail right bad did he feel,

He thought divil the rooster would he ever heel,

“Bejabers,” says Lawler, “I think I will squeal.”

“Yes, do,” says the judge to Muff Lawler.

Martin “Poet” Mulhall was 16 years old in 1876, when the first ten Irish miners were hanged for being “Molly Maguires.” He was a miner himself, who had only two years of official schooling, but had taught himself to sing and compose music. He was so moved by the tragedy of the Molly executions that he composed a song for each of the martyrs. After that, he travelled from mine town to mine town, hopping freights, singing his songs and selling broadsheets of the music to support himself. In my upcoming novel, Red Hot Summer in the Big Smoke, he is the boyfriend of my main character, Tara Doyle, who is the kid sister of Mike Doyle, the protagonist of Anywhere But Schuylkill, and one of the Mollies who got away.

Universal Buy Link: https://books2read.com/u/496Ag0

Historium Press: https://www.thehistoricalfictioncompany.com/it/michael-dunn

Meet Michael Dunn

Michael Dunn writes Working-Class Fiction from the Not So Gilded Age. Anywhere But Schuylkill is the first in his Great Upheaval trilogy. A lifelong union activist, he has always been drawn to stories of the past, particularly those of regular working people, struggling to make a better life for themselves and their families.

Stories most people do not know, or have forgotten, because history is written by the victors, the robber barons and plutocrats, not the workers and immigrants. Yet their stories are among the most compelling in America. They resonate today because they are the stories of our own ancestors, because their passions and desires, struggles and tragedies, were so similar to our own.

When Michael Dunn is not writing historical fiction, he teaches high school, and writes about labor history and culture.

Connect with Michael

Website: https://michaeldunnauthor.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MikeDunnAuthor

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Michael.Dunn.Fiction

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/michaeldunnauthor/

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Michael-Dunn/author/B0CJXGQYZ8

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/45063197.Michael_Dunn