Gwenna, heir to Ésparias, is summoned by the Empress of Casil to compete for the hand of her son. Offered power and influence far beyond what her own small land can give her, Gwenna’s strategy seems clear – except she loves someone else.

Nineteen years earlier, the Empress outplayed Cillian in diplomacy and intrigue. Alone, his only living daughter has little chance to counter the Empress’s experience and skill. Aging and torn by grief and worry, Cillian insists on accompanying Gwenna to Casil.

Risking a charge of treason, faced with a choice he does not want to make, Cillian must convince Gwenna her future is more important than his – while Gwenna plans her moves to keep her father safe. Both are playing a dangerous game. Which one will concede – or sacrifice?

Universal Book link (Amazon): https://relinks.me/B096MY4LRC

Books in My Books

Lena took the chair across from me, glancing at the books lining one wall. “If you buy any more, you’ll need more shelves.” I had already asked Roel to build them while we were away. I told her so. She smiled, a little distantly. “Will I even see you in Casil?” she asked. “Between Eudekia and the libraries?”

*****

I write about a fictional early-medieval world, and once in a while someone questions ‘books’. ‘Surely not,’ they say. ‘Wouldn’t they be scrolls?’

They are both right and wrong. By the early-medieval period, bound volumes were more common than scrolls in Europe. The predecessor of our modern book was a codex.

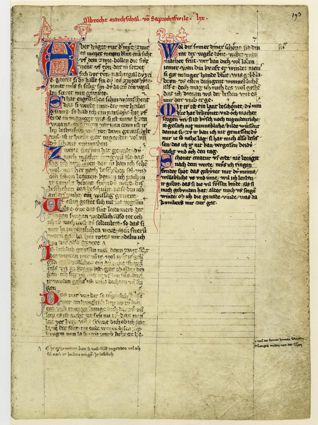

A codex consisted of sheets of papyrus or parchment or vellum (there is a fine distinction between those last two) bound between covers of wood. Codex actually means ‘block of wood’ in Latin. It is considered to be a Roman invention, possibly an expansion of the pugillares membranei, a small notebook of folded parchment. The Roman poet Martial, in the first written reference to these (Epigr. 14.184–192; 84–85 CE) suggests the pugillares membranei had advantages over the scroll. Romans exchanged gifts of literature at Saturnalia, and he pointed out that the ‘notebook’ was an excellent choice, easier to hold and take on journeys. (Much like what was said first of paperbacks, and then of e-readers, in the modern era!)

The Christian Latin poet Commodian (c 250 CE) is credited with the first use of the codex to mean ‘book’. (Carmen apologeticum 11.) There is an entire body of work from Roman lawyers and jurists as to what constituted libri (books) – bound or not, complete or not, blank or not; far too complex to go into in this article, but discussed here.

Codices, evolving from bound tablets of thin wood, may well have found early adoption in commerce and legal treatises – anywhere where comparisons, references, and frequent checking is required – on bound sheets than on a long roll. (Consider the comparison again to the modern e-reader, thinking of its flowable text as a long roll. Flipping back through a bound book is for most people much easier than trying to reread an earlier passage in an e-reader, unless one has had the forethought to bookmark it.)

In fact, it has been suggested that high-status Romans retained a preference for scrolls, looking down at codices as the books of merchants.

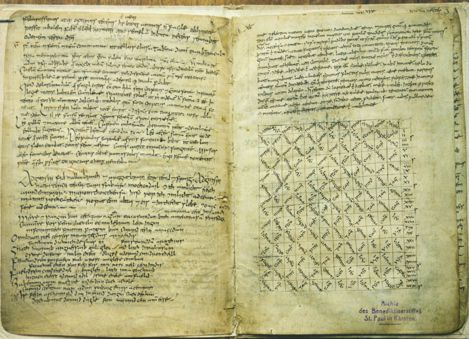

The evolution from scroll to codex took several centuries, and we can see some of the transition what we today would call formatting: scrolls used multiple columns of text, and early codices copied that format. We still see two columns today in many bibles. Christian writings are thought by many scholars to have been the impetus for the spread of codices, for several reasons: easier to transport; allowing for the same comparative study that legal codices did, and, perhaps, a desire to separate Christian writings from non-Christian.

Not all researchers agree that Christianity influenced the spread of the codex, pointing to early papyrus codices from Egypt that predate the Roman ones and do not always contain Christian writings, but those of Greek writers, specifically Demosthenes, Euripides and Plato. It is not unreasonable – in fact, it is known – that the concept of leaves of something which carried writing, bound in hard covers, arose in multiple areas with or without cultural contact. Similar binding of written sheets occurred in Mesoamerica prior to European contact. China began binding pamphlets in the 9th C, but that may have been influenced by Indian Buddhist practice in creating codices, which, in turn, may have been influenced by Rome.

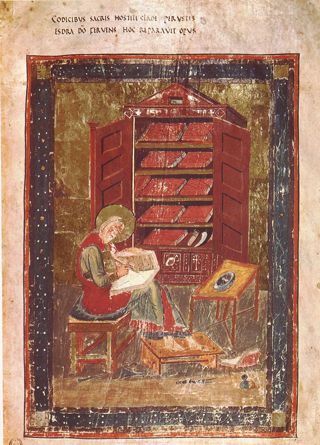

So by the middle of the first millennium CE, codices have mostly replaced scrolls across Europe and the Mediterranean lands. In the quote from Empire’s Heir, Lena says to her husband, ‘you’ll need more shelves’. This isn’t an anachronism either: Roman legal arguments over what constituted a book refers to bookshelves (which were not considered part of a library left to a beneficiary), and in this illustration from the Codex Amiatinus (c. 700), we see the storage of codices on shelves.

Books are important in my series, from the first book to the new release. They represent the transmission of history and knowledge, and play into one of the subthemes of the series, which is that language has both immense power, and yet still limitations.

References:

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/publishing/Books-in-the-early-Christian-era

Dartmouth Ancient Books Lab: https://sites.dartmouth.edu/ancientbooks/

Encyclopedia.com https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/roll-and-codex

Robert, Colin H, and T.C. Skeat, The Birth of The Codex. Oxford University Press 1987. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/rak//courses/735/book/codex-rev1.html#6

Willis, William H. A New Fragment of Plato’s Parmenides on Parchment. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 12 (1971) https://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/viewFile/9741/4487

Meet Marian Thorpe

Taught to read at the age of three, words have been central to Marian’s life for as long as she can remember. A novelist, poet, and essayist, Marian has several degrees, none of which are related to writing. After two careers as a research scientist and an educator, she retired from salaried work and returned to writing things that weren’t research papers or reports.

Her first published work was poetry, in small journals; her first novel was released in 2015. Empire’s Daughter is the first in the Empire’s Legacy series: second-world historical fiction, devoid of magic or other-worldly creatures and based to some extent on northern Europe after the decline of Rome. In addition to her novels, Marian has read poetry, short stories, and non-fiction work at writers’ festivals and other juried venues.

Marian’s other two passions in life are birding and landscape history, both of which are reflected in her books. Birding has taken her and her husband to all seven continents. Prior to the pandemic, she and her husband spent several months each year in the UK, for both research and birding, and she is desperately hoping to return.

Connect with Marian

Twitter: https://twitter.com/marianlthorpe

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/marianlthorpe

Instagram: @marianlthorpewriter

Website: https://www.marianlthorpe.com