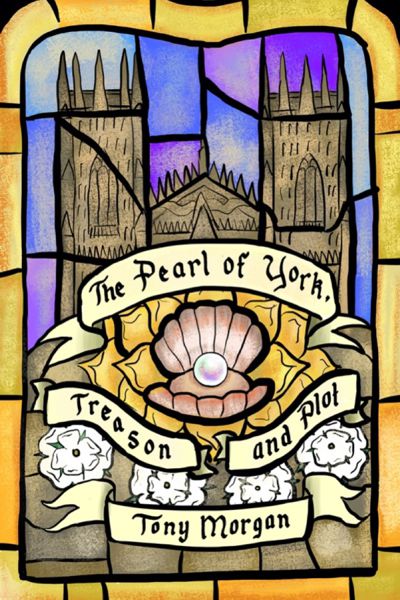

When Margaret Clitherow is arrested on the dark streets of Tudor York, her friends, led by a youthful Guy Fawkes, face a race against time to save her from the gallows. As events unfold, their lives, and our history, change forever.

This is the premise behind The Pearl of York, Treason and Plot, a new historical novel by Tony Morgan. With a number of early scenes set at Guy Fawkes’s school, St Peter’s in York, I thought it might be interesting to share some of my research, including what I discovered about schools like St Peter’s in particular.

Founded in 627 AD, St Peter’s grammar school was reputed to be the fourth oldest school in the world. The establishment was attended by a number of famous pupils, but undoubtedly the most infamous amongst them was the Gunpowder Plotter Guy Fawkes. Although detailed records no longer exist, it’s believed he attended the school between the late 1570’s and mid 1580’s.

I wanted to find out what life might have been like for Guy in a Tudor school, for example what were the hours and what subjects did he study. At first, I found these questions a little difficult to answer, but with some perseverance and a few pointers from a senior academic from the University of York, I discovered articles and books and even a PhD thesis on the topic. Eventually, I gained sufficient insight to build a fairly accurate picture.

St Peter’s was one of two grammar schools in York in the 1580’s. The other, Archbishop Holgate’s, was opened more recently, following the Reformation. St Peter’s itself has been closed for a while. When it was re-established, it wasn’t at the current location in the street of Bootham, but near to the horse fair, at the junction of Gillygate and Lord Mayor’s Walk. For those who know York, it was roughly where the Union Terrace car park is today. Perhaps one day, they’ll do an archaeological dig there, just as they did in Leicester. Who knows what they may find beneath!

It’s very likely there would have been some rivalry between the staff and boys at the two schools. I say ‘boys’ because, in common with other grammar schools of the time, St Peter’s didn’t educate girls. Thankfully, my novel includes a number of strong female characters, including the headmaster’s young cousin, Maria Pulleyn. Despite all his expensive schooling, Maria makes it plain to Guy she can read and write as well as he. If that was the case, she must have been taught elsewhere, as we find out in this excerpt from the book, as Maria passes a note for Guy to read…

Maria told me she’d left the school. Headmaster Pulleyn had placed her in the temporary care of Mistress Vavasour until secure passage could be found to transport her back to her family’s cottage in Scotton, some twenty miles to the west. It felt more like a thousand.

She placed a note in my hand and made me promise not to read it until I returned home to Stonegate.

‘You can write?’ I whispered. There was surprise in my voice.

‘Aye, I can read and write in English, and in Latin, and I’ll wager despite all your expensive schooling, I can do so just as well as you. Does this concern you?’

For a moment there was fire in her eyes. I’d not seen this before.

’No,’ I replied honestly. ‘I’m simply intrigued.’

‘I received my education at home in Scotton when the men were out at work. I was taught in the parlour by a local woman, jut as your mother was.

’What do you know of my mother?’ Again, she surprised me.

‘Plenty. Edith Jackson was a Scotton girl, wasn’t she?’

I’d never thought about this before. I’d assumed Father had taught Mother about words and numbers. The education of women folk was beyond my sphere of knowledge. I was glad all the same. When Maria was my wife, I wanted her to feel as if she was almost my equal.

I smiled and nodded at her. The candlelight from the altar created a glow around the scarf which covered her hair. How I longed to take it off. But I said nothing. I just stood there, holding her hands, looking into her eyes.

The school days began early, often at 6 am. In the book, St Peter’s opens at 7 am prompt, with harsh punishment for late arrivals, as Guy finds out to his cost. The day also finished late. From my research, the actual hours varied with the seasons.

The pupils at St Peter’s included day scholars, such as Guy Fawkes, and boarders from further afield. Fees were levied, but records from York Corporation also show payments were made from the city coffers were to educate a number of local boys for free.

Schools like St Peter’s typically had two members of teaching staff, a senior head teacher and another, who usually instructed the younger boys. Although it’s possible the boys were taught in the same room, I created two classrooms, one for the older ones and one for the youngsters.

The headmaster at the time, John Pulleyn, was tasked with running a strictly Protestant establishment. In 1571, the Archbishop of York, Edmund Grindal, indicated schoolmasters should be “of good and sincere religion, use no vain books and not teach anything contrary to the order of religion set forth” by the public authorities. Deviation from this course could land a schoolmaster in serious trouble, as John Pulleyn’s predecessor found out, languishing in prison for twenty years due to his Catholic leanings. Little wonder then that Headmaster Pulleyn attempted to keep his own Catholicism hidden.

Religious instruction and scripture were important parts of the curriculum, along with many other subjects, including Latin, Greek, the English language, arithmetic and history. The boys were also taught physical education and choral singing. A paper by York Archaeological Trust (YAT) notes in 1584 the city of York paid 40 shillings to reward John Pulleyn’s scholars for singing in York Corporation’s Common Hall, the main civic building in York. This was also the scene in real life (and in my book) of the Lord Mayor’s inauguration and Margaret Clitherow’s trial at the York Lent Assizes.

Corporal punishment was a harsh fact of school life. The YAT paper notes several boys were caught playing football within the grounds of the cathedral church of York, i.e. the Minster. They were placed in the stocks and given six strokes of the birch.

Some of the friendships Guy made at the school lasted a lifetime, although these came to an abrupt end, as did he, two decades later. His fellow pupils included two brothers from the East Riding, Kit and Jack Wright, Catholics both and future Gunpowder Plotters. Sitting alongside them was Robert Middleton. Robert left England to be trained in the Catholic priesthood. When he returned to England, he was arrested and executed.

In contrast, one fellow pupil, Thomas Cheke, prospered. The son of a Member of Parliament, Thomas was no Catholic and was knighted by King James. He became an MP like his father and lived well into his eighties.

Each of these boys has a key role in my novel, which explores the fascinating story of Margaret Clitherow’s arrest and trial, and the influence it may have had made on Guy Fawkes’s future life. I hope you enjoy it!

The Pearl of York, Treason and Plot is available now on Amazon in Kindle and paperback formats. Signed copies can also be purchased locally in Yorkshire, for example at one of Tony’s history talks.

Amazon UK link – https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0852P7RPV

Amazon US link – https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0852P7RPV

About the author:

Tony Morgan is a Welsh author and university academic. He lives in North Yorkshire, near to the birthplace of Guy Fawkes and Margaret Clitherow. In addition to writing historical novels, Tony gives history talks covering the events of the Gunpowder Plot and the life and death of Margaret Clitherow.

To date, all profits from his novels and talks have been donated to good causes. In 2020, Tony is supporting St Leonard’s Hospice in York.

For more details, visit Tony’s website – https://tonymorganauthor.wordpress.com/