As a historical novelist, I’m fascinated by the gaps in history, the silenced stories, the holes that riddle our past. For my first historical mystery trilogy, The Miramonde Series, I chose to look at this topic through the lens of art. My subjects? Women artists in Europe who lived and worked 500 years ago, during the Renaissance era. I’ve spent several years delving into their stories, and what I’ve found is astonishing.

The bad old days

First, many people are surprised to learn that there actually were women artists back then. Most of them worked under the radar. They were usually the wives, sisters, or daughters of artists. Sometimes they were nuns. If they sold their work, it was often unsigned, or attributed to the male artists in their lives—because women’s work was not valued. Women at the time were seen as inferior to men both in mind and body, incapable of achieving the same level of greatness as their male counterparts.

The greatness gap

Good thing those days are over, right? Well, not quite. The greatness gap persists. Women artists are underrepresented in galleries and museums (it’s about 70 percent men vs. 30 percent women, according to this research), and their work still doesn’t fetch the prices that the art of men commands. In academic circles, debates have still raged in the not-too-distant past over whether women artists truly are capable of greatness.

When I read H.W. Janson’s History of Art for a college art history class in the 1980s, there were zero women artists in the book. Today, out of the 318 artists featured in the book, just 27 are women. This book is mandatory reading for many college students of the arts. It tells us that throughout history, important art has been the realm of male artists. After learning this “truth” in my college days, imagine how astonished I was to learn while researching my first novel The Girl from Oto that, in fact, history is rich with many talented women artists who mostly worked anonymously and whose stories were simply never told.

(public domain)

Hmm, could greatness be linked to opportunity?

There have been lots of obstacles standing in the way of women artists’ greatness. For example, Da Vinci was celebrated for his anatomically precise work. His expertise stemmed from prolonged observation of naked bodies. His female contemporaries, on the other hand, were barred from observing nude models. One of the critiques of women artists of the past was that they weren’t very good at figurative work. Gosh, I wonder why? Until the 19th century, women weren’t allowed to draw from live models. That’s why so many of them focused on—and excelled at—the still life. It was simply an issue of what subject matter was available to them, not a question of their inherent ability to draw a human body.

One of the other challenges facing women artists of the past is that they’ve been stuffed into basements and attics, relegated to the dusty archives of Europe’s great museums. Even if museums own work by women, they rarely show it. That’s why the Prado’s show featuring Clara Peeters in 2016 was so groundbreaking. The Prado (in Madrid) had never showcased a female artist before, despite its 200-year-old history. It was only after a curator’s wife asked him if there were any paintings in the place by female artists that Flemish artist Clara Peeters’ work was retrieved from the basement and dusted off. Here’s a link to the post I wrote about Golden-age artist Peeters on my blog. I’m happy to report that the Prado has since hosted another show featuring two female old masters: Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana.

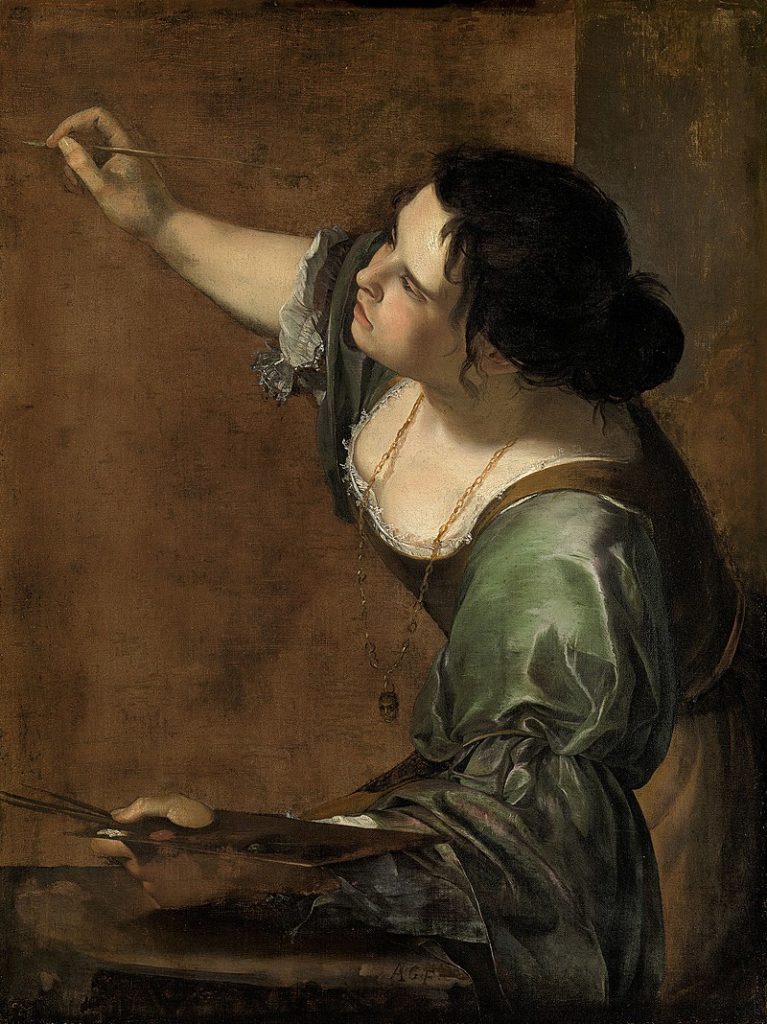

Source, Wikipedia

Another exciting development is the increasing value of women’s art at auction. Superstar Italian old master Artemisia Gentileschi is the shining star in this trend, with her work now commanding millions of dollars.

Chipping away at the problem of the woman artist—for the next generation

In the United States, we have a museum dedicated to women artists in Washington, D.C.: The National Museum of Women in the Arts. The museum showcases women’s art and educates the public about female artists of the past and present. Hopefully this will inspire more girls to take heart from examples of female greatness and become artists themselves. Here’s an eye-opening fact sheet published by the museum about gender disparity in the arts.

Amy Maroney lives in the Pacific Northwest with her family. She spent many years as a writer and editor of nonfiction before turning her hand to historical fiction. She’s currently obsessed with pursuing forgotten women artists through the shadows of history. When she’s not diving down research rabbit holes, she enjoys hiking, drawing, dancing, traveling, and reading. She’s the author of the Miramonde Series: The Girl from Oto, Mira’s Way, and A Place in the World. To receive a free prequel novella to the series, join her readers’ group at www.amymaroney.com. Follow her on BookBub at https://www.bookbub.com/profile/amy-maroney, or find her on Twitter @wilaroney, Instagram @amymaroneywrites, and Facebook.