A multiple murderer on the loose, an inheritance stolen

Injured at the start of the Indian mutiny in 1858, Scotsman Findo Gask finds himself in Melbourne during the fabled Gold Rush where he stumbles across the mystery of a stolen inheritance. Captivated by the pretty heiress, together with his new idiosyncratic friend, Erroll Rait he begins to investigate for her, travelling back to London, Edinburgh, the Scottish highlands and then to Melbourne again, uncovering multiple murders before falling foul of a sinister plot to add himself and his client to the list of victims.

Time Travel to the Western Isles

I’ve always been interested in history because it can be a great teacher and the study of historical events allows you to put modern-day events into context. And Scottish history, in particular, continues to fascinate me because of the underlying David vs Goliath elements of Scotland’s place in the world and the unquenchable spirit that courses through the Scottish character. As a writer, it is a multi-stranded, multi-coloured cloth that never fails to provide a richness underpinning the resulting tapestry.

My latest novel, The Case of the Emigrant Niece, set in the late 1850s/early 1860s, includes scenes in Edinburgh, Dunfermline and the Morvern peninsula (as well as England, Melbourne and the Victorian gold fields). There is one major problems setting a story in the mid-19th century if you are going to have your characters travel extensively. And that problem is twofold: time and setting.

The reality is that it took an awfully long time to get anywhere in 1860 – especially in the Scottish highlands. To create a genuine atmosphere that brings your readers into the story, you need to dig into the history to understand not only the physical nature of things back then but also the social conventions and attitudes of the time. Both take effort and, dare I say it again, more time, and this time, my own. In my personal opinion, researching the past to create a true, realistic backcloth is, however, a sine qua non if you are writing historical fiction.

I faced this problem in my book, The Case of the Emigrant Niece, when my heroes found themselves on the trail of the villain. They were based in Edinburgh, the villain in Dunfermline, and he had absconded to a wee village by the name of Bun a Mhuilinn on the Morvern peninsula across the water from the Isle of Mull.

A few years back I rented a cottage in Drimnin, close by Bun a Mhuilinn with my father, brother and uncle. We arrived late in the day – the journey took longer than we had anticipated – and all we had with us (besides a bottle of Jura single malt) was a bar of chocolate which served as dinner for the four of us that evening. Early the next morning, I drove the 10 miles south on a single-track road to Lochaline and stocked up at the ‘local’ store before returning in triumph with eggs, bacon, lorne sausage, tomatoes, onions, morning rolls and a huge appetite.

The visit must have stuck in my memory (or perhaps it was the sizzling breakfast) for when I was writing about the villain’s escape, it seemed like a great place for him to hide out – especially as in 1860, there were no roads worth the name to the outer reaches of the Morvern peninsula and I recall how even in modern times it seemed really out of the way. I have also sailed on the Hebridean Princess several times visiting the northern isles, the Inner and Outer Hebrides and places in between and cannot speak too highly of the experience, so the thought of having my heroes sail up the Sound of Mull was also appealing….

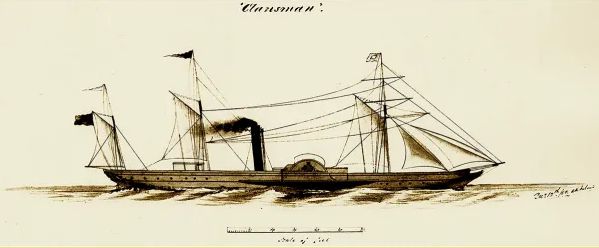

So there we were, my heroes had discovered that their quarry owns a but and ben in Bun a Mhuilinn and, like them, I begin trawling through newspapers of the time to figure out how to get them there. There were two ways to get to Mull and the environs then – via the Crinan canal, which was known as the ‘Swift’ service and the route south of the Mull of Kintyre, known as the ‘all-the-way” route. The canal route was shorter and faster – taking a steamer to Crinan and then continuing on to destinations north. However, Lochaline was not a major destination point which necessitated our trip on the ‘all-the-way’ service. The steamer they booked was the Clansman, a name still borne by a Caledonian McBrayne ferry today that operates out of Oban.

At the time, it was something special, described as, “the magnificent screw-ship Clansman… one of the finest vessels afloat, and having cost upwards of £40,000”. The advertisement in the Greenock Advertiser advised that it would call in at Lochaline (weather permitting), which was about as close as any scheduled service would get to their destination.

Lochaline may ring a bell for any who have read about the sad evacuation from St. Kilda in 1930. It was here, on a barren dock, that the last permanent residents of St. Kilda landed with their few possessions and promises ringing in their heads of a better life. The promises were, however, ephemeral and dreams were quickly dashed. It was a distressing end to a way of life that today could be more viable thanks to internet connections, wind and tide power and improved communications although it is still not unknown for boats to have to stand off the island because of bad weather. The entire archipelago is today owned by the National Trust for Scotland and, a World Heritage Site, is one of the few in the world to hold this status for both its natural and cultural qualities.

The idea of connecting the most remote parts of the western isles by steamboat had taken hold by 1820. The Highland Chieftan had already gone as far as Stornoway from the Clyde through the Crinan canal and Sound of Mull and had covered the distance in ‘the remarkably short space of 35 hours from Glasgow – a distance of 235 miles notwithstanding she had to steam the currents which run so violently in the Sounds of Skye and Mull’[1]

These currents had been well known to locals for centuries and particularly the Gulf of Corryvreckan – a narrow strait between the islands of Jura and Scarba where one of the largest permanent whirlpools in the world (at the north end of Jura) makes this place a very dangerous stretch of water for the unwary. The currents here can reach over 10 knots which can produce waves over 9m high and a fiercesome whirlpool some 100m wide and 30m deep. The whirlpool is caused by a giant rock that soars to within 30m of the surface which forces the sea upwards, causing huge waves.

The Corryvreckan whirlpool is something that has fascinated people for centuries. There is a legend that a king promised his daughter to a Viking prince if he could spend 3 nights out on a boat in the whirlpool. Up for the challenge, the prince obtained three cables, one made of hemp, one made of wool and one woven from the hair of maidens. The first night he was able to withstand the whirlpool, and the second, too. But on the third night the cable made from maidens’ hair was not equal to the power of the waters and he was sucked into the deadly vortex and perished. A warning indeed to those who seek to challenge nature.

It was the arrival of powerful steamships that opened up this route to previously inaccessible locations and 40 years later, as Rait was checking things out, the paddle-steamer Clansman and the single-screw steamer Clydesdale were both operating on the Stornoway route.

[1] From the Herald of December 22, 1820

Amazon.com: https://amazon.com/Case-Emigrant-Niece-Erroll-Mysteries-ebook/dp/B0BD1N83CQ

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Case-Emigrant-Niece-Erroll-Mysteries-ebook/dp/B0BD1N83CQ

Meet David Cairns

David Cairns, the Baron of Finavon (an ancient Scottish title), has always been a student of history and has the ability to create an atmosphere and three–dimensional experiences with his writing style. Until recently, he was a technology entrepreneur. He has lived and worked on four continents and as a result has experienced the history of London and Boston, the buzz of Chicago, Nashville and Silicon Valley, the pioneering atmosphere of the South African bush, the lazy lifestyle of the Bahamas, the cultural diversities of Europe and the laid-back lifestyle of Australia, which is where he makes his home these days.

Website: https://cairnsoffinavon.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheDavidCairns