The Case of the Hydegild Sacrifice thrusts readers into the shadowy aftermath of one of America’s darkest moments—the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

Join Major Gask and Erroll Rait as they unite with the Pinkertons to unravel the sinister secrets of the Hydegild Sacrifice—a case that threatens to shake the foundations of a nation still reeling from war.

History holds its breath. Will the truth finally be revealed?

The Policy of Hydegild: Vicarious Punishment

After finishing my latest Major Gask Mysteries novel, I found myself—as I often do—wrestling with a title. The story turns on the dark web surrounding the assassination of Abraham Lincoln: a conspiracy in which the hand that pulled the trigger was punished, but the minds behind the act escaped unscathed. For a time, I considered calling it The Pawn Sacrifice—a nod to the expendability of those who serve power. But then I recalled a haunting custom from Britain’s distant past, a practice that perfectly captured this notion of punishment displaced. It was called Hydegild.

In the glittering yet treacherous world of Tudor and early Stuart England, even princes were not beyond reproach—though they were, by divine decree, beyond the rod. The royal body, anointed with holy oil, was considered sacred, an earthly vessel of divine will. To strike it was to strike the order of heaven itself. And yet princes, being boys, were mischievous, disobedient, sometimes cruel. How, then, to correct one who could not be touched? The answer lay in a chilling compromise: a substitute child, of noble birth, who would be whipped whenever the prince transgressed. This was Hydegild—from hyde, meaning skin, and gild, meaning payment or recompense—the “payment of the skin.”

The Sacred Skin

The origins of the practice reach back to the Anglo-Saxon world, where every wound and injury carried a wergild—a “man-price”—that translated violence into value. Each finger, each eye, each tooth had its cost. The principle of Hydegild extended that logic into the realm of morality. Since the prince’s sacred flesh was untouchable, another’s must pay in its place. What the treasury settled with coin, Hydegild settled with pain.

To understand the belief, one must remember that medieval kingship was a sacred calling. The monarch’s body was not merely mortal; it was divine property. Even the heir apparent was to be protected from the contaminating touch of punishment. Yet mischief demanded correction, and thus another’s back became the ledger upon which royal guilt was written.

The Whipping-Boy

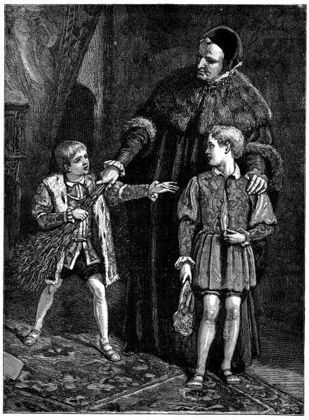

In the courts of the Tudors and early Stuarts, the system was formalised. Royal children were surrounded by companions of noble families—playmates, scholars, and confidants. Among them, one boy bore a peculiar burden: when the prince erred, this companion would be flogged in his stead.

The theory was simple and cruel. The prince, it was believed, might feel no fear of punishment himself, but he might feel compassion. Watching a beloved friend suffer for his disobedience would stir his conscience, planting the seed of moral responsibility. It was pain by proxy, empathy as education.

History gives us a few glimpses of these strange friendships. Prince Edward, later Edward VI, had Barnaby Fitzpatrick. Prince Charles, later Charles I, had William Murray, who was beaten for Charles’s youthful lapses, and later rewarded with a title and lifelong favour. Their bond, forged in those peculiar lessons, endured into adulthood—proof that pain, even misplaced, can create unbreakable ties. Yet one suspects that, facing his accusers in 1649, Charles may have wished the old arrangement still applied.

The Theology of Substitution

Beneath this odd ritual lay a deep vein of theology. Christianity, after all, is built upon the idea of substitution—the innocent suffering for the guilty, Christ’s scourged flesh redeeming mankind. The whipping-boy embodied that doctrine in miniature: the prince, God’s anointed on earth, could not be scourged, so his failings were transferred to a surrogate.

The act reaffirmed a world where the king’s person represented something beyond human jurisdiction. To punish him would be to rupture the divine order. And so Hydegild became a sacred performance of power—an echo of the “two bodies of the king,” one mortal and fallible, the other political and perfect. The whipping-boy absorbed the pain that the royal body could not endure, preserving the illusion of sanctity.

A World of Unequal Flesh

For the child who bore the lash, the role was both suffering and opportunity. He endured humiliation, but he lived at the heart of power. Parents of noble families sometimes sought the position for their sons, gambling pain for the promise of influence. The system thus perpetuated itself: cruelty rationalised by ambition, pain transformed into currency.

Within the schoolroom, a strange triangle of authority emerged. The tutor represented law and divine order; the prince embodied privilege; the whipping-boy symbolised the suffering subject. The lesson, at least in theory, was moral awakening—that one’s actions, however exalted one’s birth, could inflict pain on others. But whether it truly bred compassion or merely hardened young rulers to the suffering of others is harder to say.

The Waning of Hydegild

By the late seventeenth century, the world that sustained Hydegild was fading. The Enlightenment brought new ideas of childhood, discipline, and kingship. The divine right of monarchs was giving way to the constitutional principle that even a king was accountable. The royal body, once untouchable, was reimagined as simply human. With this shift, the old practice seemed both barbaric and absurd. Education began to value reason over fear, conscience over spectacle. The last whipping-boys faded into history, their strange service consigned to anecdote. Yet the logic of Hydegild—the transference of guilt and the shielding of the powerful—was far from gone.

The Modern Echo

The term “whipping-boy” survived, becoming a metaphor for anyone made to suffer another’s punishment. Its ghost lingers in every era where responsibility is displaced: the scapegoated minister, the expendable soldier, the corporate subordinate sacrificed to save a superior’s reputation. Power still seeks its surrogates; authority still demands its offerings of pain.

When I think of the Lincoln conspiracy—of Booth and his accomplices executed while others escaped behind influence and privilege—I see the same moral pattern. The players change, the costumes modernise, but the principle endures: someone must pay, even if not the true guilty.

The Price of Privilege

The story of Hydegild reminds us that power’s immunity comes at a cost. In sparing the prince’s skin, it demanded another’s. It was, in miniature, a portrait of monarchy itself—a structure built on substitution, sanctity, and sacrifice. The whipping-boy was not just a punished child; he was a symbol of a world where pain flowed downward, where innocence could not protect one from suffering, and where privilege was maintained through the suffering of others.

Today, Hydegild exists only in metaphor, but its moral shadow stretches long. Whenever the powerful escape consequence and others bear the weight of their misdeeds, we are witnessing the old payment of the skin. It is a debt that never seems fully settled, a currency that power still spends freely.

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Case-Hydegild-Sacrifice-Assassination-Conspiracy-ebook/dp/B0FYD9XHKJ

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Case-Hydegild-Sacrifice-Assassination-Conspiracy-ebook/dp/B0FYD9XHKJ/

Meet David Cairns of Finavon

David Cairns of Finavon was, until recently, a technology entrepreneur. He has lived and worked on four continents and, after many years making his home in the Perthshire highlands, these days makes he stays on the Gold Coast with his Australian wife. He is the author of The Helots’ Tale series – Downfall and Redemption – and the Gask and Rait Mysteries series, The Case of the Wandering Corpse, and The Case of the Emigrant Niece , and The Case of the Beth-El Stone

Webpage: www.CairnsofFinavon.com

Visit David on Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheDavidCairns