Northern New England, summer, 1688.

Salem started here.

A suspicious death. A rumor of war. Whispers of witchcraft.

Perched on the brink of disaster, Resolve Hammond and her mother, Deliverance, struggle to survive in their isolated coastal village. They’re known as healers taught by the local tribes – and suspected of witchcraft by the local villagers.

Their precarious existence becomes even more chaotic when summoned to tend to a poisoned woman. As they uncover a web of dark secrets, rumors of war engulf the village, forcing the Hammonds to choose between loyalty to their native friends or the increasingly terrified settler community.

As Resolve is plagued by strange dreams, she questions everything she thought she knew – about her family, her closest friend, and even herself. If the truth comes to light, the repercussions will be felt far beyond the confines of this small settlement.

Based on meticulous research and inspired by the true story of the fear and suspicion that led to the Salem Witchcraft Trials, THE DEVIL’S GLOVE is a tale of betrayal, loyalty, and the power of secrets. Will Resolve be able to uncover the truth before the town tears itself apart, or will she become the next victim of the village’s dark and mysterious past?

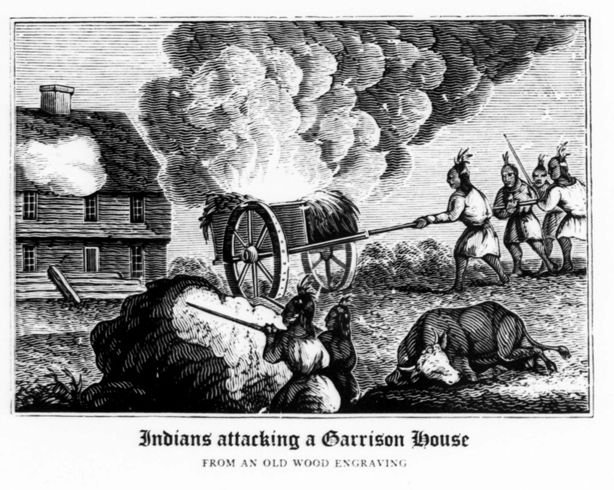

Relationship between Indigenous Native Tribes and Anglo-European Villagers, 1688

By the summer of 1688, relationships between the Anglo-Europeans who were attempting to settle on what is now the Maine coast north of Boston and Indigenous Native tribes were, in a word, terrible.

Not that they had ever been good. The earliest Anglo explorers, arriving almost two centuries earlier, had usually reacted to overtures from local tribes by either killing them or snatching them and taking them back to London to be displayed as curiosities. Occasionally, as in the case of the notorious Squanto, they were returned. Usually, they died. Huge numbers of those not treated to enforced trips to London and other European capitals died, too. They were felled in part by violence, but mostly by Anglo-European diseases they had no immunity against. It is impossible to be completely accurate, but best estimates suggest that in the one hundred to one hundred and fifty years after first contact in 1492, 85 – 90% of North American Indigenous populations were wiped out by smallpox, influenza, measles and other pathogens passed to them by Anglo-Europeans.

Reading the early annals of New England, I am often overcome by the optimism and generosity of Indigenous tribes who, in the face of such unpromising history, tried again, and yet again to cooperate, trade, and live in some semblance of negotiated peace with these weird, pale interlopers who came to settle among them. Because, as the 16th century ended and the 17th began, that was the problem: the word ‘settle’.

As Wendy Warren has pointed out in her brilliant New England Bound (Norton 2016), many if not most incipient empires are founded on the desire to extract – gold, minerals, furs, fish, lumber, whatever. The Anglo-Europeans who began to arrive in New England in earnest in what became known as the Great Migration of 1630 -40 were, however, not after what they could grab and take away, although there was certainly some of that. Instead, what they were after was land. And they wanted not only to own it, but to occupy it.

The fact that what is now New England was already occupied, and had been for generations, was seen as little more than an inconvenience. Or as a complete chimera. Because the Anglo-European’s who arrived with very set ideas – not only about God, civilization, and families – but also about land use. They knew how ‘civilized’ people cultivated land, and they knew that what they saw wasn’t it. Unable to recognize, and largely uninterested in learning about Indigenous land use, they perceived at best, empty ‘virgin’ territory. At worst, an ungodly wilderness crying out to be saved by divine mandate, namely theirs. Either way, it was obvious to them that the land was there for the taking. So, they took it.

‘Treaties’ were made. ‘Sales’ were negotiated. But as Bruce Trigger has pointed out in his classic Natives and Newcomers (McGill 1985) it is hard to talk about, much less enforce the legitimacy of agreements when one side, in this case the Indigenous, had no concept of what a ‘treaty’ was, certainly not in the legalistic sense that British officials with their bits of paper relied on. And that was before you even got to the legions of scam artists insisting they had ‘bought’ vast tracts of lands that Indigenous peoples had no sense of ‘ownership’ over, at least in the European sense, for handfuls of beads.

To make matters worse, a majority of the 20,000 or more immigrants who arrived in New England in the space of a decade between approximately 1630 and 1640 were essentially middle class. Some of these people chose to leave England and, to a lesser extent, Scotland and Ireland, out of religious conviction – they were Puritans, or Protestant Separatists of some kind. But by no means all of them were. A lot of them were families and individuals who saw no room for advancement, no way they could own anything they could build on. So they embarked for The New World, and their slice of what was perceived and promoted as virgin territory – an empty land where they could claim their plot.

This was a problem. Not only because, inevitably, sooner or later deciding to ‘claim your plot’ on what is already somebody else’s plot is going to cause considerable tension; but also because they had no idea how to do what they wanted to do with the plots once they got them. On the whole, these were shop keepers, mildly educated younger sons, school teachers, the odd minister. Traders with ambitions. Men and women who may have had convictions, but mostly had no idea how to build a shed, much less a barn or a road. And so, they drowned. They fell in to bogs. They froze to death in snow banks, and got hopelessly lost in the woods. And by the time they did finally clear land, they found they needed labor to work it.

The first war between Anglo-Europeans and Indigenous tribes broke out in 1637 in Southern New England. In her groundbreaking Bretheren by Nature (Cornell, 2015), Mary Ellen Newell makes a convincing case that the Pequod War, as it became known, was fought largely to procure Indigenous slave labor for settlers and settlements. This bloody conflict was followed by the even bloodier King Philip’s War, 1675-76, which, as Jill Lepore argues in In The Name of War (Random House 1999) essentially set the stage for American racial conflict. More immediately, although the war ended officially when King Philip, as Anglo Europeans called the Indigenous leader, was killed and had his head carried on a pike across Massachusetts, the conflict really just slid north. More or less continuous raids, burnings, and random killings finally escalated into what would become known first as King William’s war, then as Queen Anne’s war. The fighting would continue for seven decades before finally running out of steam in 1749.

This is background to The Devil’s Glove, and it colored every interaction, and every contingency of day to day life, especially in the villages and outlying settlements where villagers lived closest to Native tribes.

By the summer of 1688, when the story begins, the coast of Maine, home of Resolve and Deliverance Hammond, was a tinder box set to explode. Trust was at an all time low, on both sides. The local Abenaki, backed by the French, had finally found a gifted and charismatic leader in the sachem, Madockawando. Determined to halt northward settlement, he and his sons – and his son in law, the French Baron de Castin – formed a powerful anti-Anglo confederacy based at the head of Penobscot Bay. Bringing the war to the enemy, Madockawando raided as far south as Dover, New Hampshire. His men were formidable warriors, and they meant business. Those who were not killed were often taken captive – sometimes to be held for ransom, sometimes to replace Indigenous family members killed in earlier conflicts.

Terrified, the local settlers responded by forming militias. These were made up of, and led by, all stripes of available men. Some were experienced. Most were not. Some were patient and sensible. Most weren’t. Unfortunately, they made blunder after blunder, often attacking native factions that would otherwise have stayed, if not neutral, at least not completely hostile. Cycles of escalating and often unprovoked violence turned those who might once have been friends into enemies.

And yet, there were Europeans and Anglo-Europeans who managed to build bridges. Or at least approach their Indigenous neighbors with open enough minds to allow mutual misunderstanding to create a ‘middle ground’ where some form of communication was possible. These instances were not frequent – on the whole, Anglo Europeans of all sorts and classes were convinced of their superiority over Indigenous people whom they saw as ‘savages’ – but they did happen. The story of Resolve and Deliverance Hammond being sheltered by a local tribe during King Philip’s War is based on a true example. And men like John Alden and Philip English, who were essentially privateers and traders, and who saw Indigenous peoples as trading partners, did exist – and understood that war, never mind killing the goose that brought you the golden egg, usually in the form of furs, was bad for business.

The French, on the whole, fared better, in part because, at least in the beginning, New France was seen as a trading enterprise that depended on Native cooperation. The fact that New France was Catholic, and simply that it was French, never mind that it got on fairly well with Indigenous populations – only made settlers and villagers in Massachusetts and The Eastward, as Maine was called at the time, more suspicious. Language, faith, world views and ambitions were basically completely at odds. The fact that each side perceived the struggle as ‘cosmic’ – perceived their own survival as dependent on the annihilation of the other – made communication difficult, and cooperation unlikely. Too often, those who tried, paid a price. That is, essentially, the story of The Devil’s Glove.

This title is available to read on #KindleUnlimited.

Universal Link: https://books2read.com/u/4EN58l

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0BWSD5SVL/

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BWSD5SVL/

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B0BWSD5SVL/

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B0BWSD5SVL/

Meet Lucretia Grindle

Lucretia Grindle grew up and went to school and university in England and the United States. After a brief career in journalism, she worked for The United States Equestrian Team organizing ‘kids and ponies,’ and for the Canadian Equestrian Team. For ten years, she produced and owned Three Day Event horses that competed at The World Games, The European Games and the Atlanta Olympics. In 1997, she packed a five mule train across 250 miles of what is now Grasslands National Park on the Saskatchewan/Montana border tracing the history of her mother’s family who descend from both the Sitting Bull Sioux and the first officers of the Canadian Mounties.

Returning to graduate school as a ‘mature student’, Lucretia completed an MA in Biography and Non-Fiction at The University of East Anglia where her work, FIREFLIES, won the Lorna Sage Prize. Specializing in the 19th century Canadian West, the Plains Tribes, and American Indigenous and Women’s History, she is currently finishing her PhD dissertation at The University of Maine.

Lucretia is the author of the psychological thrillers, THE NIGHTSPINNERS, shortlisted for the Steel Dagger Award, and THE FACES of ANGELS, one of BBC FrontRow’s six best books of the year, shortlisted for the Edgar Award. Her historical fiction includes, THE VILLA TRISTE, a novel of the Italian Partisans in World War II, a finalist for the Gold Dagger Award, and THE LOST DAUGHTER, a fictionalized account of the Aldo Moro kidnapping. She has been fortunate enough to be awarded fellowships at The Hedgebrook Foundation, The Hawthornden Foundation, The Hambidge Foundation, The American Academy in Paris, and to be the Writer in Residence at The Wallace Stegner Foundation. A television drama based on her research and journey across Grasslands is currently in development. THE DEVIL’S GLOVE and the concluding books of THE SALEM TRILOGY are drawn from her research at The University of Maine where Lucretia is grateful to have been a fellow at the Canadian American Foundation.

She and her husband, David Lutyens, live in Shropshire.

Connect with Lucretia

Website: http://LucretiaGrindle.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BookWhisperer.ink

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/bookwhisperer/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bookwhispererink/

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/author/lucretiagrindle

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/827521.Lucretia_Grindle