Two men, two dreams, two new towns on the plains, and a railroad that will determine whether the towns—one black, one white—live or die.

Will Crump has survived the Civil War, Red Cloud’s War, and the loss of his love, but the search for peace and belonging still eludes him. From Colorado, famed Texas Ranger Charlie Goodnight lures Will to Texas, where he finds new love, but can a Civil War sharpshooter and a Quaker find a compromise to let their love survive? When Will has a chance to join in the founding of a new town, he risks everything—his savings, his family, and his life—but it will all be for nothing if the new railroad passes them by.

Luther has escaped slavery in Kentucky through Albinia, Will’s sister, only to find prejudice rearing its ugly head in Indiana. When the Black Codes are passed, he’s forced to leave and begin a new odyssey. Where can he and his family go to be truly free? Can they start a town owned by blacks, run by blacks, with no one to answer to? But their success will be dependent on the almighty railroad and overcoming bigotry to prove their town deserves the chance to thrive.

Will’s eldest sister, Julia, and her husband, Hiram, are watching the demise of their steamboat business and jump into railroads, but there’s a long black shadow in the form of Jay Gould, the robber baron who ruthlessly swallows any business he considers competition. Can Julia fight the rules against women in business, dodge Gould, and hold her marriage together?

The Founding tells the little-known story of the Exodusters and Nicodemus, the black town on the plains of Kansas, and the parallel story of Will’s founding of Lubbock, Texas, against the background of railroad expansion in America. A family reunited, new love discovered, the quest for freedom, the rise of two towns. In the end, can they reach Across the Great Divide? The Founding is the exciting conclusion to the series.

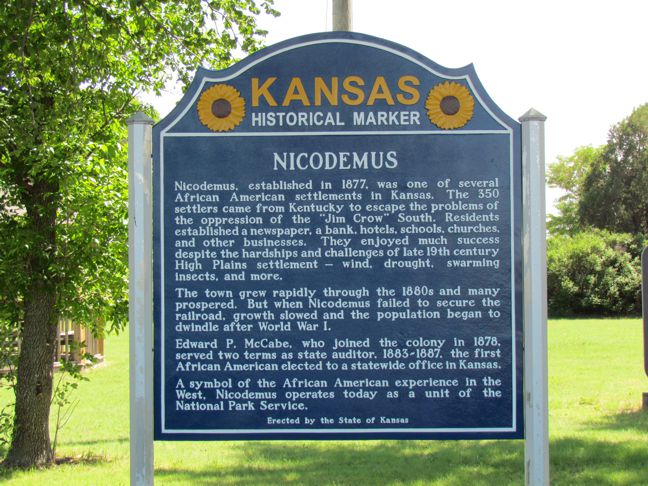

Nicodemus, the all-black town

The process of research for the Founding was lengthy and detailed. One of the most interesting aspects was researching Nicodemus, the all-black town founded on the Kansas prairie. After I moved to Kansas in 2017, I heard about Nicodemus from people at church and decided it was a must-visit. I was already well into writing the first book of the Across the Great Divide series, The Clouds of War. When I discovered the phenomenon of black towns, and that many of the original founding families had come from Lexington, Kentucky, like my character Luther, it simply fit right into the story.

Nicodemus is now a National Park Service historical site, largely due to the efforts of Angela Bates, director of the Nicodemus Historical Society, and a sixth-generation descendant of a founding family.

Many people assume that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery, or that slavery in the US was ended at Appomattox with the Confederate surrender at the end of the Civil War. Neither is completely accurate. Lincoln’s proclamation did not affect the border states, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and West Virginia, where he feared that erasing slavery might cause them to secede.

“I hope to have God on my side,” Abraham Lincoln is reported to have said early in the war, “but I must have Kentucky.” Unlike most of his contemporaries, Lincoln hesitated to invoke divine sanction of human causes, but his wry comment unerringly acknowledged the critical importance of the border states to the Union cause.” – Lincoln on Kentucky

The border states were slave-holding, but did not secede, and were not held to be in rebellion. “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free;” – the Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation advanced the cause of freedom but left many people in chains.

Likewise, the surrender on April 9, 1865, ended most active fighting (the last battle was in Texas, on May 13), but until the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, slavery and the fugitive slave laws were still legal in the United States. Though widely ignored, the Fugitive Slave Law technically permitted a formerly enslaved person in a free state to be returned to their “owner”. The 13th Amendment passed in January, 1865, but was not ratified until the end of that year, on December 6.

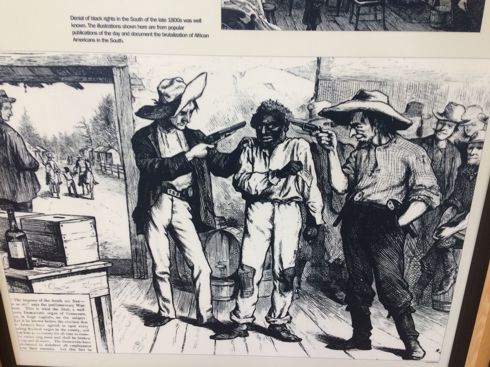

Even once slavery formally ended, many states passed laws to perpetuate unfair treatment of black people, known as the Black Code or Jim Crow laws. “Black Codes restricted black people’s right to own property, conduct business, buy and lease land, and move freely through public spaces. A central element of the Black Codes were vagrancy laws. States criminalized men who were out of work, or who were not working at a job whites recognized.” (Wormser, The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow (2003), p. 8.) An example is the Oregon exclusion clause in its state constitution which prohibited blacks from residing there. Similarly, Connecticut, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and New York enacted laws to discourage free blacks from residing in those states. Moreover, freedom did not mean citizenship – free black people were not considered U. S. citizens until the 1866 Civil Rights act, and ratification of the 14th Amendment, on July 9, 1868. This meant that black people could not, in many states, enter into contracts or have their marriages recognized.

The inability to enter contracts excluded most black people from the Homestead Act. Despite the supposed guarantee of “forty acres and a mule”, most blacks were excluded by legal means or chicanery from owning land.

Segregation often became violent. “Despite all their efforts at self-protection, Blacks fell prey to nightriders, who picked them off one by one if they appeared concerned with the political well-being of their people. Leaders of Republican clubs stood out as especial targets of these terrorists, who also silenced or drove away white Republicans. (Painter, Nell Irvin. Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction (p. 10). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.)

The KKK rode several times a week around Lexington, burning, lynching, raping, and terrorizing blacks and whites that supported them.

With this background, it becomes easy to see why black people, especially in the deep South, longed to find a place of peace and freedom. Once the Homestead Act applied to black males, a trickle that became a flood started to flow out of the South, to the western states, forming a movement known as the Exodusters. In response to the persecution of free black people, they began to seek places not controlled by whites. One such movement, inspired by Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin DeLaney (black) was the “Back to Africa” movement – but it was not overly popular. Most blacks in America had never seen Africa, and had no desire to strike out for a land so foreign and unfamiliar. Many instead set their sites on land to the west, like Kansas. It was unfamiliar, but still America.

“In mid-1879 a Black Texan groped toward a description of this mood of alarm among the freed people: There are no words which can fully express or explain the real condition of my people throughout the south, nor how deeply and keenly they feel the necessity of fleeing from the wrath and long pent-up hatred of their old masters which they feel assured will ere long burst loose like the pent-up fires of a volcano and crush them if they remain here many years longer.” (Painter, Nell Irvin. Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction (p. 184). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.)

At first, the black migration was welcomed, and hailed as a boon to the state of Kansas, with the Governor lauding the benefits – but it was short-lived. As boat and train loads of poor blacks came, the meager social services of Atchison, Leavenworth, and other towns on the Missouri river were stretched to the limit. Towns began shipping the migrants to other towns to handle the influx, reminiscent of the recent handling of Latin American immigrants in modern times.

“Insult was added to injury when Mayor Fortescue of Leavenworth telegraphed Mayor John C. Tomlinson asking if Atchison could care for more migrants, for his city had an ample supply and two boatloads were expected there momentarily. [62] The answer was emphatic and to the point: No. We have all the city can provide for. I hereby respectfully notify you and the city of Leavenworth that the city of Atchison will hold you and your city responsible for the paupers you caused to be sent here yesterday.” Kansas Exodusters

Some groups came with a plan. “By 1881 African Americans emigrants had established twelve agricultural colonies in Kansas: Nicodemus, Hodgeman, Morton City, Dunlap, Kansas City–area Colony, Parsons, Wabaunsee, Summit Township, Topeka-area Colony, Burlington, Little Coney, and the Daniel Votaw Colony.” Black Towns

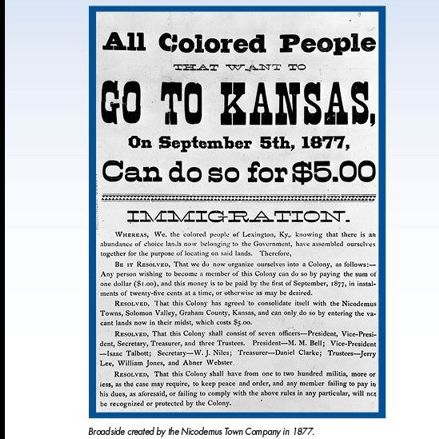

Nicodemus was founded by the combination of Reverend Simon Roundtree, black minister from Lexington, Ky. and white land speculator William R Hill. Hill was mainly looking to get rich, and it was easier for a white man to get land than a black man. Roundtree, formerly enslaved, was looking for a way out for himself and his congregation, a church near Lexington, Kentucky. He recruited families to go to Kansas, based on Hill’s advertisement. Each family paid $5 (about $140 today) and received their own plot of land. What Hill didn’t tell the prospective emigrants is that there was literally nothing there.

They walked from Dry Lick, Kentucky to the train at Sadieville, about thirty miles. Most had never been on a train before. They took the train west to Ellis, Kansas, and walked another thirty miles to the townsite for Nicodemus. Women, children, and grandparents, were all on a quest for freedom. The first group had hundreds of people. Angela Bates has just made a documentary film reenacting this journey. When they arrived, there was a bare prairie, with no trees, and only the Solomon River for water. With no lumber to build, they dug holes in the ground. They arrived in the autumn, with no crops harvested, and a Kansas winter coming. The little colony would have starved, but for the generosity of the Pottawatomie Indian tribe bringing food.

More groups came on the train, from Kentucky and eastern Kansas. There was a Buffalo Soldier family. One group arrived with measles and had to be quarantined. Each year, the colony grew, and prospered more. They freighted in lumber for buildings. There was a school, a church, a blacksmith shop, a general store, a hotel, and a baseball team. All that was missing was the railroad.

The Founding records the struggle of black people searching for freedom and a new home. The series traces a black family, Luther’s family, from plantation life in Kentucky through the Underground Railroad escape, Canada, the Colorado gold rush, to Nicodemus. Join them for the ride of your life.

Michael Ross’s YouTube channel HistoricalNovelsRUS Nicodemus 1 has re-enactments and stories from Nicodemus descendants. Travel back in time with us.

Universal Link: https://books2read.com/u/3yVJVn

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0BL9438XP/

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BL9438XP/

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B0BL9438XP/

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B0BL9438XP/

Meet Michael Ross

Michael Ross is a lover of history and great stories.

He’s a retired software engineer turned author, with three children, and five grandchildren, living in Newton, Kansas with his wife of 39 years. Michael graduated from Rice University and Portland State University with degrees in German and software engineering. He was part of an MBA program at Boston University.

Michael was born in Lubbock, Texas, and still loves Texas. He’s written short stories and technical articles in the past, as well as articles for the Texas Historical Society.

Across the Great Divide now has three novels in the series, “The Clouds of War”, and “The Search”, and the conclusion, “The Founding”. “The Clouds of War” was an honorable mention for Coffee Pot Book of the Year in 2019, and an Amazon #1 best seller in three categories, along with making the Amazon top 100 paid, reviewed in Publisher’s Weekly. “The Search” won Coffee Pot Cover of the Year in 2020, and Coffee Pot Silver Medal for Book of the Year in 2020, as well as short listed for the Chanticleer International Book Laramie Award.

Connect with Michael

Website: HistoricalNovelsRUS.com

Twitter: https://mobile.twitter.com/michaellross7

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/historicalnovelsrus

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-ross-87505026/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/HistoricalNovelsRUs

Book Bub: https://www.bookbub.com/profile/michael-l-ross

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/Michael-Ross/e/B07PTB7WMK/ Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/19005014.Michael_L_Ross

Thank you for hosting Michael L. Ross with such a fascinating guest post.