Gold Camps of California—1850s

When Joaquin Murrieta’s older brother and cousin head for the riches of the California gold fields, he cannot resist the restless desire to follow. In a bold move, he convinces Rosita, the young woman he loves, to run away with him under cover of darkness. They follow the irresistible lure of the future they might grasp for their own in America, the land of dreams.

Instead, they face deep prejudice and explosive violence that leads to unspeakable tragedy, and forces Joaquin to set his sights on being a leader of men—becoming a legend, in the process. To make a place for himself and his people, he strikes back at the whites and the devastating, perpetual hatred they feel toward the Mexicans. Determined not to fail, to carve out a place in this vast land for himself and his followers, Joaquin Murrieta fights back with a stubborn will that is sure to win all…

But can he succeed? With his band of outlaws—and then, an army of patriots—he is determined to drive the Americans from the land that had so recently belonged to his beloved Mexico. It seems an almost unattainable achievement to some, but Joaquin cannot consider failure in this obsession.

With Joaquin’s brother murdered, and his band of renegades on the run, they must make their final stand and face Murrieta’s evil nemesis—cruel California Ranger Harry Love—who has been given carte blanche to do whatever it takes to kill Murrieta and drive his followers out of California for good. As the battle rages in a final showdown between Love and Murrieta, it’s kill or be killed.

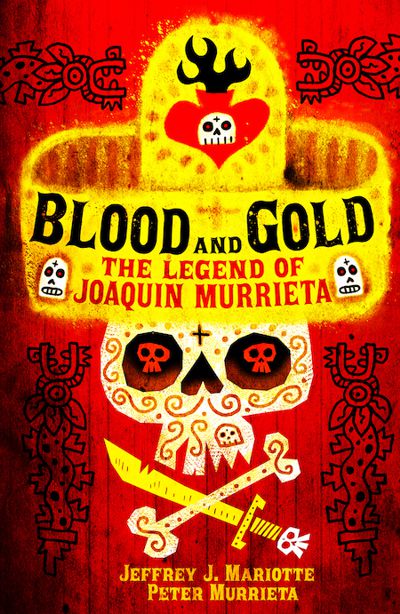

Only one of them can walk away from BLOOD AND GOLD…

California Gold Rush became an American phenomenon instead of a Mexican one

At the end of the war called by Americans “the Mexican War,” by Mexicans “the American War,” and by most historians today “the Mexican-American War,” Mexico ceded to the United States vast tracts of its land holdings in what was, until then, northern Mexico. President James Knox Polk had—perhaps inadvertently, hoping Mexico would simply fold at the sight of American forces marshaled at the border and Navy ships off its coastline—provoked the war in the interest of furthering the concept known as Manifest Destiny. When hostilities ceased, Mexico signed away land, from Texas west to the Pacific Ocean and north to Oregon. American Nicholas Trist and a delegation from Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, ending the conflict and handing the U.S. all or part of what would become ten states.

The U.S. Senate made some changes to the treaty and ratified it on March 10. With the changes, it went back to Mexico, which accepted the changes. Polk found out on June 7, and he declared the treaty in effect as of July 4.

What Mexico didn’t know—what even Polk didn’t know at the time—was that nine days before the initial signing, back on January 24, an American carpenter named James Marshall was inspecting the deepening of a millrace not far from Sutter’s Fort in California. Looking into the water, he spotted gleaming objects that turned out to be gold.

It took time for the news to spread, obviously. Had Mexico known what the result of Marshall’s discovery would be, it might have fought harder or held out longer, or both. Instead, the California Gold Rush became an American phenomenon instead of a Mexican one.

As it happened, once word passed beyond the borders of the brand-new state, Americans and Mexicans alike poured in, hoping they too might find gold. The growing city of San Francisco emptied out. Most of the workers at Sutter’s Fort had already abandoned their posts in favor of scouring the landscape and searching every creek and river for color. Soon, others—mostly men—flowed into California, creating transient communities, tent cities, in which the only thing the newcomers had in common was the desire to get rich quick.

What had been a pastoral economy based largely on the export of hides from vast Californio cattle ranches became one based on the profits of merchants selling goods—picks and shovels, blankets and boots—to the gold seekers for inflated prices, usually paid in gold dust or nuggets.

As more and more gold was pulled from the earth, more and more seekers came from around the world. Chile, France, China, Great Britain, and other nations were well represented. And with them came others, cleverly planning to profit from the miners by providing things they wanted as well as those they needed, including the distractions of women, liquor, and gambling.

With the influx of strangers, and particularly the arrival of dozens, then hundreds, and then thousands of foreigners, chasing after what America believed was its own riches, California’s fledgling government tried to favor the interests of white Americans over those others’. Thus was born the Foreign Miners’ Tax of 1850, among other legislation. And where laws barely existed or were rarely enforced, Americans took “justice” into their own hands. Racial violence was more than tolerated, it was endorsed, however tacitly. Hangings became relatively frequent events. “Foreign” camps were raided or burned out.

Into this fraught situation came a young Mexican named Joaquin Murrieta, traveling with his new wife Rosa (or perhaps Carmen, records aren’t entirely clear) Feliz, Joaquin’s brother Jesús, and their cousin Manuel Duarte, also known as Tres Dedos, or Three-Fingered Jack, to Americans. They left Trincheras in Sonora, Mexico, and traveled north on the El Camino del Diablo—the Devil’s Highway—with others heading for the gold fields. Mining was a common occupation in Sonora, and those who ventured north often fared well because they already had the necessary skills, as opposed to the merchants and soldiers and farmers and tradesmen who streamed westward across the United States.

But doing well, in that country and in that time, brought with it unintended consequences. White Americans who wanted the treasure for themselves objected to the sight of Mexicans growing rich while they struggled. And here, we veer from history into legend, because what happened to Joaquin and his party is poorly documented, and the bare facts have often been retold for dramatic effect.

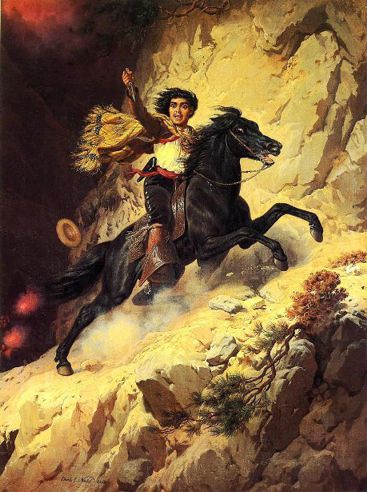

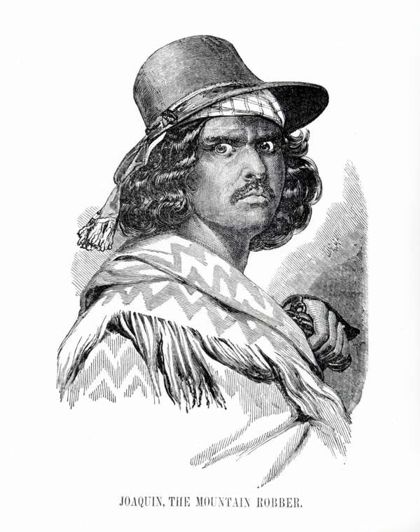

The outline of the story is usually the same. Jesús was hanged on the pretense of his having stolen a horse, a mule, or a burro. Joaquin and Rosa were attacked, Joaquin beaten to within an inch of his life and Rosa raped and murdered. In retaliation—or out of desperation—Joaquin became an outlaw, stealing from Americans and spreading the wealth in Mexican communities. His exploits became legendary in California. Whites feared him and Mexicans idolized him. California’s legislature created an entirely new law-enforcement agency, the California Rangers, specifically to run him to ground, appointing a lawman named Harry Love to lead it and offering a substantial award for Joaquin’s capture or death.

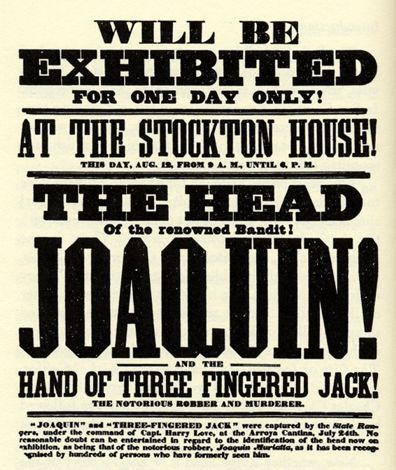

Which Joaquin were they after, though? As Murrieta’a notoriety grew, other bandits started calling themselves Joaquin, either because they wanted to be feared and respected, or because Murrieta told them to, in order to confuse the authorities and create the impression that he was everywhere at once. Finally—or so some stories say—Love and the Rangers found Joaquin’s band, killed him, and cut off his head and the three-fingered hand of Tres Dedos. Preserved in alcohol, Joaquin’s head toured the state, becoming a major attraction until it vanished in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

In writing Blood and Gold: The Legend of Joaquin Murrieta, Peter Murrieta—a fifth generation descendant of Joaquin’s, from a family where the first male child in each generation is still named Joaquin—and I studied dozens of books about the California Gold Rush, and every text we could find about Joaquin’s life and his legend.

We were less concerned with what is historically definitive—largely because little detail exists historically—than with presenting what was and what might have been, inspired by stories passed down through generations of Peter’s family. We wanted to capture the essence of the era, and to tell the definitive version of the tale that inspired, among other things, the creation of Zorro (and through him, nearly every other superhero known today), and that still resonates today, of people fighting back against oppression and racism with every tool at their disposal.

The newsletter of the Montana Library Society said “Blood and Gold: The Legend of Joaquin Murrieta by Jeffrey J. Mariotte and Peter Murrieta is a contemporary epic. Sweeping in scope, full of adventure and thrills and drama, this book is the type of tome you lose yourself in.” And in the Los Angeles Times, Gustavo Arellano wrote that the “600-page novel zips through its action-filled saga with the vigor of Louis L’Amour (and with a hell of a plot twist at the end).”

We’re thrilled by the critical reception to our story—and to Joaquin’s story, one that has survived the ages and continues to inspire today.

Amazon: https://amazon.com/Blood-Gold-Legend-Joaquin-Murrieta-ebook/dp/B09HL81YT9

Meet Jeffrey J. Mariotte

Jeffrey J. Mariotte has written more than fifty books, including supernatural thrillers River Runs Red, Missing White Girl, and Cold Black Hearts, horror epic The Slab, and the teen horror quartet Year of the Wicked. Other works include the acclaimed thrillers Empty Rooms and The Devil’s Bait, and—with his wife and writing partner Marsheila (Marcy) Rockwell—the science fiction thriller 7 SYKOS and Mafia III: Plain of Jars, the authorized prequel to the hit video game, as well as shorter works. He has also written novels set in the worlds of Deadlands, Star Trek, CSI, NCIS, Narcos, 30 Days of Night, Spider-Man, Conan, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, and more. Three of his novels have won Scribe Awards for Best Original Novel, presented by the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers. He’s also won the Inkpot Award from the San Diego Comic-Con, is a co-winner of the Raven Award from the Mystery Writers of America, and he has been a finalist for the Bram Stoker Award from the Horror Writers Association, the International Horror Guild Award, the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America, the Peacemaker Award from the Western Fictioneers, and for his comics writing, the Harvey Award and the Glyph Award.

He is also the author of many comic books and graphic novels, including the original Western series Desperadoes, the horror series Fade to Black, action-adventure series Garrison, and the original graphic novel Zombie Cop. He has worked in virtually every aspect of the book business, as a bookstore manager and owner, VP of Marketing for Image Comics/WildStorm, Senior Editor for DC Comics/WildStorm, and Editor-in-Chief for IDW Publishing, and a publishing consultant for various companies. When he’s not writing, reading, or editing something, he’s probably out enjoying the desert landscape around the Arizona home he shares with his family and pets.

Connect with Jeffrey

Website: http://www.jeffmariotte.com

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JeffMariotte

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/JeffreyJMariotte

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jeff_mariotte/

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Jeff-Mariotte/e/B001IOBHPY