In 219 BC the war clouds gather as Hannibal sacks the Spanish city of Saguntum. Rome, egocentric, belligerent and bent on supremacy of the Mediterranean lands, cites provocation and thus war with it‘s old enemy, Carthage in what is known to history as the second Punic war.

As the two superpowers collide; Spain, Gaul and finally Italy itself become battlegrounds as Hannibal spreads slaughter, fire and sword.

Into this war of giants steps Baldor Targa of Carthage. Falsely accused and In fear of retribution, pursued and finally trapped in Numidia, Baldor fights for his life against the brother of the man he has slain. Realising he will always be a hunted man he enlists in Hannibal’s army as a mercenary warrior.

Suffering a baptism of fire in Spain, he then marches through Gaul and across the Alps, fighting Gallic tribes as well as snow and ice; emerging onto the northern plains of Italy to confront the legions of Consul Publius Scipio and his son Cornelius and where fate will take a twist that affects all their lives.

Ancient War Elephants – The ‘battle tanks’ of antiquity

Since early times man has used animals as an aid to war, the elephant being no exception. The Indians, Macedonians, Seleucids, Carthaginians, Romans, Nubians et al, all deployed war elephants at some time and to varying degrees of both success and failure.

Both Asian and African elephants were drafted into service depending on the county seeking them and availability of the animal. Elephants, like horses generally shy away from loud noise so are not naturally battle ready and need to be trained to accept the uproar, mayhem and carnage that goes along with combat. Each elephant comes with a handler or mahout, who was supplied with an ankus or goad to help steer and control the animal and a mallet and a metal spike that was to be driven into the elephants head/neck to kill it should it run amok. How successful this was in practice is not clear but judging by the sometime chaos, when an animal turned back on its own side, for example at the battle of Zama in 202 BC when some of the Carthaginian elephants turned back on their own left wing, the idea doesn’t seem to have worked too well.

There is evidence of armour for elephants with metal tusk tips, protective headgear of leather and chain mail, quilted body coverings and even leg protection. There are also hints in ancient writings that elephants were dosed with palm wine or beer before combat to embolden them and make them less inhibited to anger and fighting (not unlike drunken humans!) However, categorical proof is harder to find and thus historians remained divided on the question.

Just like modern tanks today that need fuel and maintenance to operate effectively, elephants require a huge amount of food and water in order to survive. Depending upon size, they can consume approximately 150 Kg of food and 60 – 90 liters of water per animal on a daily basis. Multiply this by the number of animals in your army and you are adding considerably to your baggage train.

As far as fame or notoriety for the use of war elephants goes, Hannibal Barca of Carthage and his crossing of the Alps, along with thirty-seven elephants is what springs to mind for most people when mentioning elephants. With the possible exception of one elephant, ‘Surus’ (The Syrian? Possibly, imported from Syria and from ancient Seleucid stock and most likely an Asian elephant by breed) Hannibal used North African Forest elephants, a sub species of the much larger African Bush or Savanna elephant. This North African or Forest elephant is much smaller than its southern cousin at around eight feet to the shoulder, where the Savanna elephant can reach eleven feet to the shoulder. Thus, with Hannibal using this smaller elephant and despite many paintings to the contrary, it remains highly unlikely that a turret/fighting platform/howdah was placed on its back for men to fight from. It is possible that one or two archers or javelin men could ride behind the mahout though they would just sit splay legged across the elephant’s back. This higher platform making it ideal for missile troops to shoot from.

There is proof of turrets being placed on elephant’s backs by the much later Persian Sassanid empire but whether this was just for use when laying siege to a fortress, military parades or open battle is unclear, these animals would also be most likely Asian elephants.

The elephant itself is the actual weapon, both physically and psychologically and both soldiers and horses required training to deal with them. The unfamiliar spoor of elephants panics horses that have not been exposed to the beasts and any soldiers untrained against an elephant charge, would in most cases also panic and break formation. However, the Romans and others soon learned how to best deal with a charging elephant. Lots of noise from trumpet blasts is one way to turn the animal away or—and probably safer—by opening avenues in their ranks, into which the, more than likely frightened beast would run down to escape. Thus saving the soldiers and their formations and allowing the beast to be disposed of or captured later. Again, the battle of Zama in 202 BC is a good example of such tactics, here Hannibal’s poorly trained elephants that hadn’t ran amok amongst his own men were shepherded between the Roman maniples and away from the battle.

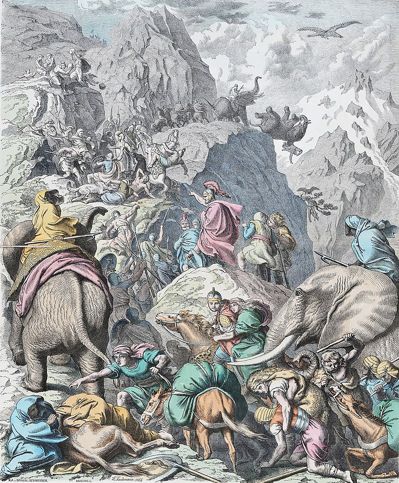

Hannibal’s war elephants and crossing of the Rhone 218 BC.

River crossings for any army be it modern or ancient pose difficulties. Even when you have control of both river banks you still need to move men, baggage and in the case of the ancients, animals across as well. Today’s military have options of mechanical amphibious vehicles, pontoon bridges or even bridge laying machines for the smaller rivers, for ancient armies life was not so simple.

Pontoons such as that built across the Hellespont by Xerxes 1st in 480 BC take time and require many ships or boats plus timber for the roadway. When Hannibal had to cross the wide Rhone on his way to the Alps and Italy in 218 BC, he had neither the time nor the ready materials for such a solid bridge. Thus, boats of any type, rafts and even tree trunks were secured and used to ferry his men and horses across the river, the elephants however were not so easy.

Elephants are natural swimmers and can swim well for long periods and long distances; the problem comes however, when trying to cross a very wide, deep and swift flowing river like the Rhone. Swimming them across is possible but not without them becoming separated and this can cause problems as Hannibal found out.

Initially, attempts were made to load the elephants onto large rafts built of oak logs secured at the river’s edge, the leading matriarch however, refused to step onto the raft and the other elephants seeing her reluctance followed in the same vein. Instead, Hannibal’s troops and no doubt supported by his engineers then built larger rafts some 50 feet in length complete with corral rails then joined four of them together, securing them and taking them out a third to halfway across the river. The timber was then covered in earth and rushes to give the appearance of solid ground and the matriarch was led out with the troop in her lee. This time she went as bidden to the raft at the end of the would-be road; once filled to capacity with the matriarch and the first few elephants it was separated from the other three rafts and towed across the river by small row boats. Loading the remainder of the elephants on the next rafts went quickly and well, the animals keen to follow the matriarch and others. However, as the first raft with the matriarch on board moved further away on the swift current, the separated troops began trumpeting to each other in panic and chaos ensued.

Being a highly social and family orientated animal, elephants are loath to be separated, thus they panicked, trumpeting, rearing and crashing into one another smashing the raft fencing, while trampling and killing mahouts and raft crews before tipping or falling from the rafts into the river.

All the elephants made it safely across the Rhone either still on the rafts or by swimming, many of the mahouts, handlers and raft crews not being so lucky.

Amazon.com: https://amazon.com/gp/product/B07D12921T

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Lions-Wolf-Orphan-Cub-ebook/dp/B07D12921T

Meet Garrett Pearson

Garrett Pearson was born and raised in the northeast of England; he is married with two grown sons. Captivated by the long and turbulent history of his homeland he became a dedicated student of English history and ancient military history. He is an author of Historical Fiction, a member of the Historical Novel Society and guest blogger to English Historical Fiction Authors (EHFA) and Mercedes Rochelle (Author). This is his first book on Dark Age England and the Saxon/Viking wars, he has also written three books on the Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome.

Connect with Garrett

Email: garrettpearsonauthor@gmail.com

Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/Garrett13853937

Facebook: http://www.GarrettPearson.net