A young entrepreneur from a youthful Philadelphia, chances upon a French aristocrat and his family living on the edge of the frontier. Born to an unwed mother and raised by a disapproving and judgmental grandfather, he is drawn to the close-knit family. As part of his courtship of one of the patriarch’s daughters, he builds a château for her, setting in motion a sequence of events he could not have anticipated.

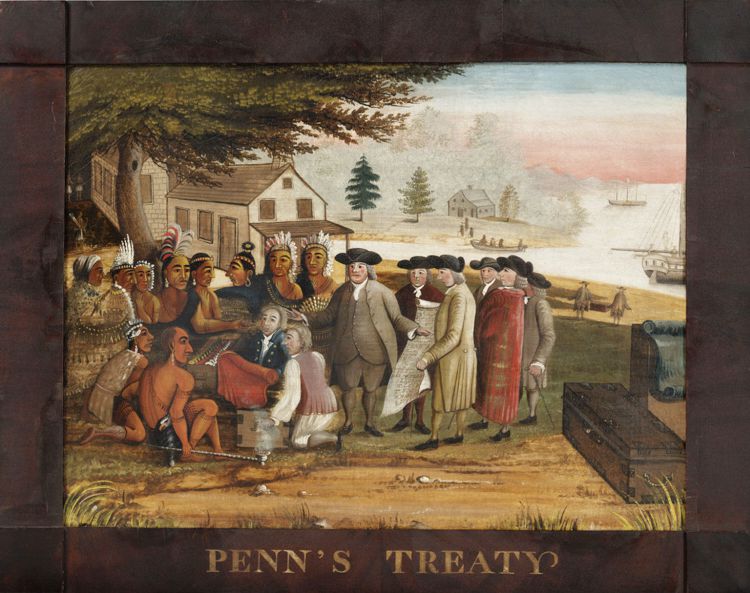

Native Americans of Southeastern Pennsylvania

I have always been fascinated by the Native Americans of southeastern Pennsylvania. An impoundment near where I lived was named after the Lenape that were indigenous to the area, and other Native American names were commonplace. Even the farm where I grew up held clues to a pre-European past. It had a wood that once held a native encampment and artifacts such arrowheads turned up from time to time, whispering of a past that could only be imagined.

The Lenape of the area were welcoming to the early Europeans and played a role in the newcomers’ survival, sharing their native crops of maize and beans in addition to venison, waterfowl, and other game. They found in William Penn an honorable man, who traded fairly with them and kept his promises (albeit when it came to land the natives didn’t really know what they were trading). That said, Penn could not have known the devastation that would follow first contact. He couldn’t have known that the diseases the Europeans carried would wipe out ninety percent of the native population. And he couldn’t have known that the few who survived would have little defense against the vigilantism of the lesser lights of his own growing community.

With the foregoing in mind, a little known fact is the role adoption played in the native population. Colonial mythos has it that the Europeans met fierce native resistance, and that European technology and moral character seized the day. European technology was definitely a factor, but the imagined superiority of character has to be ascribed to cultural bias. Let us not forget that the colonial experience was initially based on the pursuit of corporate profits, and included the active capture of natives to bolster the numbers of Africans already enslaved. Slave trading was especially a factor in the West Indies and the southern colonies around Charleston. But it was a factor in the Puritan north and, to a lesser extent, in the Pennsylvania middle colony as well. Once the natives realized they were being overrun, there were indeed skirmishes with the colonists. But people die in battle, and even if the natives won a conflict, any losses represented a serious attrition that compounded the precipitous decline they had already experienced.

Adoption, then, became a hot pursuit. This was true of the Lenape and the nearby Susquehannock, and especially true of the Haudenosaunee to the north, whom the French called the Iroquois. In some cases, intertribal wars were fought with the express intent of capturing so-called enemies who could then be adopted. Women and children were readily adopted, but also men, once they were socialized into the new tribal group.

In Chateau Laux, Lawrence Kraymer was adopted into a Susquehannock tribe. One could say that he was accepted because he had saved one of the native children from a cruel fate at the hands of white renegades, but such adoption would not have been unusual under most circumstances. Lawrence’s native family nursed him through the fugue state he was in following some of the recent events in his life. They gave him sustenance and the time he needed to heal, and then gave him the gift of choice as to where he wanted to live.

The sad story of the Susquehannock involves a staggering level of ill-treatment by the colonials. Except for a few who traveled north and assimilated with the Haudenosaunee, very few survived and their culture faded. In many ways, language is culture, and the only remnant of their language that I am aware of is the book A Description of the province of New Sweden, now called, by the English, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: M’Carty and Davis, 1834), which is acknowledged at the end of Chateau Laux. Vocabulary is a foundational building block in any culture, and when I read through this dictionary, I could almost feel the presence of a lost people. Granted, the book was based on a Swedish interpretation of another culture’s spoken language, and is fragmentary at best. Moreover, the words were recorded by a colonial missionary, who, while he may have had the best intentions, would have represented yet another aspect of the European invasion. But as one of the few remnants we have left of a generous and noble people, it is a gift from the past.

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Chateau-Laux-Novel-David-Loux/dp/1954065019

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Chateau-Laux-David-Loux/dp/1954065019

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/Chateau-Laux-David-Loux/dp/1954065019

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/Chateau-Laux-Novel-David-Loux/dp/1954065019

Barnes and Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/chateau-laux-david-loux/1138853964

Kobo: https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/chateau-laux

Meet David Loux

David Loux is a short story writer who has published under pseudonym and served as past board member of California Poets in the Schools. Chateau Laux is his first novel. He lives in the Eastern Sierra with his wife, Lynn.

Connect with David

Website: https://wiregatepress.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ChateauLaux

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/56342730-chateau-laux

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/David-Loux/e/B08WZ8MVT5

Thank you for this post!

David Loux