“Hard work is the only way in this life,” the old man said. “Sweat and time. That is what you need to make it here. Sweat and time. There are no short cuts. No parading in front of strangers, so that they can laugh at you and call you names. That is not work. That is embarrassing!”

Jack Lemm was a household name in Wales between the Wars, famed as a Boxer and the Strongest Man in Wales, a Music Hall act and a Fairground sensation. But behind the scenes, he fought a different fight – against the disapproval of his father.

THE WELSH HERCULES tells the story of Jack, from his humble beginnings on Swansea Docks through to becoming a renowned Boxing coach and fairground star. It takes him through two World Wars, as a survivor of the Battle of Jutland and the Swansea Blitz, and introduces a whole new world of Showmen, acrobats and colourful characters.

But at its heart, Jack’s story is one of family – of the challenges met, the hearts won and the enduring romance of a Showman and his wife.

Music Halls

If you were a Music Hall act, you had to be of hardy stock.

The Music Hall was a very specific type of British entertainment. Although slightly analogous to Vaudeville in America, it’s safe to say it was its own beast.

The Music Hall tradition started in the taverns and coffee houses of the 18th Century. Especially in the big cities, these were places where people (specifically men) could share, food, drink and stories. A song might be sung, jokes told – everyone could join in. The atmosphere was friendly and anarchic, far different from the more Upper Class dominated theatres of the day.

By the 1850’s, the early Victorian era, such entertainment had moved out of the public houses and into purpose-built Music Halls (although they still drew a lot of their acts from local entertainers – Jack, for example, was first spotted performing feats of strength to workmates and spectators on Swansea sands). That anarchic spirit stayed with it, however.

The audience were encouraged to eat and drink and smoke whilst the show took place, and it was not unusual for acts to have to strain to be heard against the noise coming from the stalls. It was common for the audience to throw objects at the ‘turns’ if they were not popular – food, of course, but also bottles, old boots, iron rivets and even dead cats!

The bigger Music Halls in the cities, especially London where the rivalry between the neighbouring Alhambra and the Empire was intense, sought to calm down the gentlemen in the audience by allowing ladies in (Middle class women had often been kept out of taverns and Supper Clubs, although Working Class women had long been frequenters of the public house). This backfired, however, when it became obvious that the men didn’t want their wives there and instead Music Halls became a venue for prostitutes to walk up and down the aisles, touting for customers.

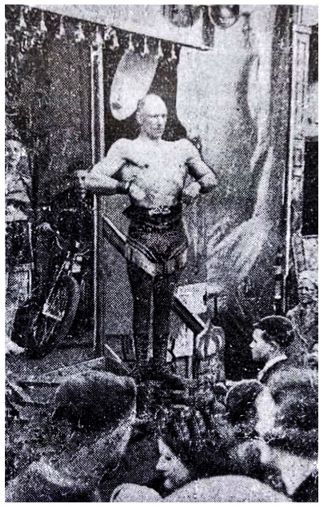

Jack Lemm’s career in Music Hall centred on the smaller venues in Swansea, Wales, such as the Palace Theatre, run by Billy Coutts. As a strongman, he was one of the ‘novelty acts’ that filled out the bill and brought people in.

A typical performance could feature up to 20 acts, each performing a signature turn. They could be on for 5 minutes or 20 minutes, depending upon their skill and the audience’s tolerance of it, but it was not unknown for a complete programme for the evening to last up to 4 hours. Singing was the backbone of the evening – bawdy songs, comedic songs, patriotic songs and sentimental songs were all heard and lustily accompanied by the audience. Interspersed with this there were comedians, mime artists (who you’d imagine would be a particularly hard sell to this crowd), ventriloquists, acrobats (including strongmen like Jack), impressionists and female and male impersonators, the precursor to today’s drag Queens and Kings.

The artists were contracted to a manager usually, and managers could run more than one venue, so it was not unknown for the same artist to appear on one stage early in the evening before having to hotfoot it across town to another for a later slot. Those who became famous through it – Marie Lloyd, who started at The Eagle in London aged 14, Dan Leno, Harry Relph or Little Tich as he was better known – could earn the princely sum of upto £80 a week, but most of the acts worked for a pittance and survived with a day job alongside their theatrical work (Jack remained a dock worker throughout his Music Hall years).

But the heady days of Music Hall did not last long. In 1875, there were 375 Music Halls in Greater London, and hundreds more around the country, but several things were conspiring against them.

Most obviously, the acts couldn’t take the pace for too long. Things came to a head when venues decided to create two separate bills on the same night – one show starting at 6:45pm and the other at 9pm. Both shows were identical but the performers were only paid once, for the evening, as they always had been. This extra work, and the loss of other work by no longer being able to get between venues in time, led to a strike in 1907. The managers were forced to capitulate, but the writing was on the wall. A lot of the acts went into the more sedate world of Variety and still others, like Jack, transferred their talents to the touring fairground where they were more in charge of their own fates.

The Great War also had an effect on Music Hall – although many still turned out reduced shows in aid of the war effort, they could not hide the fact that a lot of the acts had gone off to fight and never returned.

The final blow, however, came from within. From early in the 20th Century, Music Hall bills included a brief interlude for the Electric Bioscope projection. It may have only been grainy black and white images projected onto a screen suspended over the front of the stage, but it was popular and people flocked to see images from around the country and the world. It was the start of cinema and by the time the First World War was over there were picture houses everywhere – and quite a few were reconfigured Music Halls.

Jack Lemm learnt his trade as an entertainer treading the boards of Music Hall and it was important to us as authors that we showed as much of this rich world as we could before taking him on to his later adventures in the Wars and as a showman in fairgrounds. There will probably never be another form of entertainment like Music Hall and it was a pleasure to try and convey some of its many charms and challenges.

Available on Kindle Unlimited

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Welsh-Hercules-Snapshots-Strongmans-Life-ebook/dp/B09XML71XR

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Welsh-Hercules-Snapshots-Strongmans-Life/dp/B09XLNWHTS/

Meet David & Steven

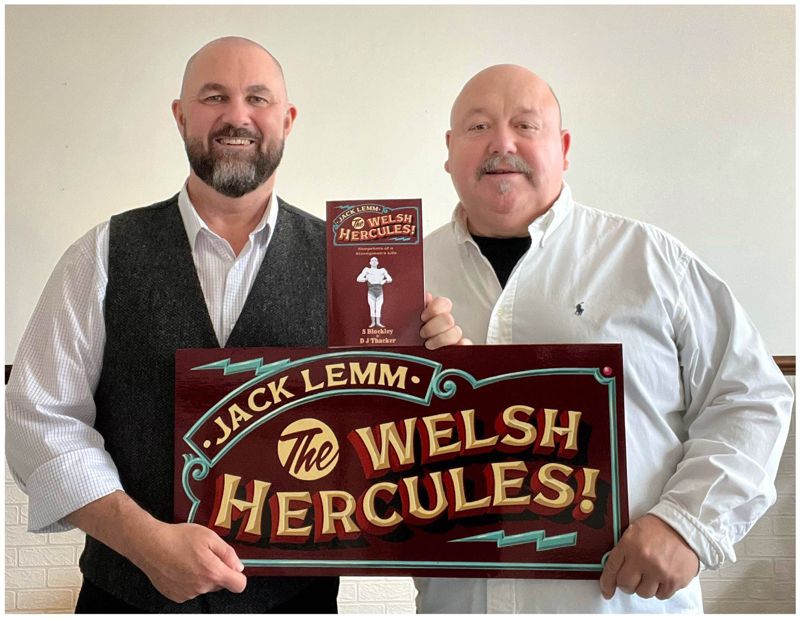

David J Thacker has spent most of his working life in the Theatre and has loved it for even longer. In 2001, he wrote and took ‘Save Our Theatre – A Play for Young People’ to the Edinburgh Festival, and he has also written the libretto for a modern oratorio that has been performed around the world.

Prior to THE WELSH HERCULES, he had written mainly in the horror / dark fantasy genre, with titles such as ‘The Red House’ (longlisted for a British Fantasy Award), ‘Once: A Belmouth Tale’ and ‘The Last Rat Child’.

Steven Blockley, his co-author, is the great grandson of Jack Lemm and comes from a showman family. THE WELSH HERCULES was his first novel.

Connect with David & Steven

The Welsh Hercules (@welsh_hercules) • Instagram photos and videos

David J Thacker (@davidjthacker) • Instagram photos and videos

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JohnBro38909291