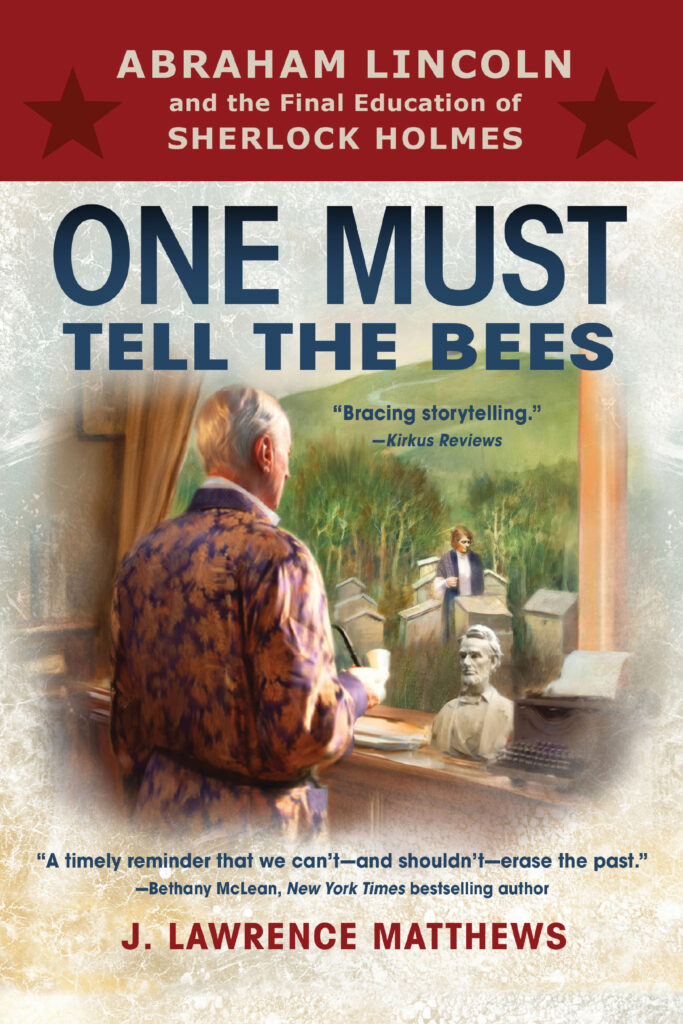

Blurb

“President Lincoln is assassinated in his private box at Ford’s!”

When those harrowing words ring out during a children’s entertainment in Washington on the evening of April 14, 1865, a quick-thinking young chemist from England named Johnnie Holmes grabs the 12-year-old son of the dying President, races the boy to safety, and soon finds himself enlisted in the most infamous manhunt in history.

One Must Tell the Bees is the untold story of Sherlock Holmes’s journey from the streets of London to the White House of Abraham Lincoln and, in company with a freed slave named after the dead President, their breathtaking pursuit and capture of John Wilkes Booth. It is the very first case of the man who would become known to the world as Sherlock Holmes, and as readers will discover, it will haunt him until his very last.

It begins in 1918 in the English countryside where the world’s greatest detective has retired to tend his bees and write his memoirs — memoirs that reveal the full story of his journey to America, first as a junior chemist at the DuPont gunpowder works in Wilmington, then as a companion for young Tad Lincoln on what turns out to be the evening of President Lincoln’s assassination — and finally as an unsung participant in the electrifying manhunt for the assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

At a time when Western history is being reexamined and retold, old heroes cast aside and statues torn down, and even the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, “the Great Emancipator,” is questioned, One Must Tell the Bees is a timely reminder that our history deserves to be understood before it is entirely undone.

An Interview with J. Lawrence Matthews

What is it about Sherlock Holmes that originally captured your attention and inspired years of research?

When I graduated from reading Hardy Boy mysteries as a kid, the flawed genius of Sherlock Holmes came as a complete revelation — the cocaine bottle was something you didn’t see Frank and Joe Hardy messing with! That opened this messy adult world to me, and of course Holmes’s voice came across so distinctly, and the plots moved along so effortlessly, that it was as if Conan Doyle just sat down by the fire with his pipe and started telling a ripping good yarn, and I’ve been reading them ever since. To this day, I’d maintain a handful of the Holmes titles are among the best short stories ever written, Hemingway included. The straw that stirs the drink, in my view, is the pair’s friendship: Watson dulls Holmes’s brilliance and makes him easier to tolerate. Don’t we all want to possess that kind of insightful, rational intelligence — and yet, as adults, don’t we also see the dark side to that kind of focused, monomaniacal lifestyle? It’s good vs evil in a timeless Victorian setting, and it never grows old.

What made you decide to focus on Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation?

I’ve been a student of the Civil War for decades, ever since I read a book on Lincoln and mentioned to my wife that even after four years of college I knew nothing about the Civil War. Couldn’t even say which Jackson — Andrew or Stonewall — was the Confederate general and which the American president! So she bought me a book on the war and I began reading, and I’ve been reading about it, and visiting the battlefields, ever since, trying to grasp what it was all about. And what it was about, at first, for the North anyway, was restoring the Union even if that meant slavery in the South remained intact. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 changed everything, however, because it freed slaves wherever Northern troops won a victory. America could no longer go backwards: with every victory of Northern troops came freedom for slaves in that region of the South. That’s quite a profound thing, and quite underappreciated today. I have long felt its impact should be less misunderstood, and Sherlock was an excellent vehicle to do that.

Walk us through your research and writing process for stories based during a time you didn’t live through.

I’ve been effectively doing “research” for 30 years as a student of the Civil War, so I wrote the story of Holmes in America straight through — from his arrival near the time of Lincoln’s reelection to the manhunt for Booth — with a little help from Wikipedia to get dates right. Then I went deep into many of my old books, plus many new ones, in order to make certain the action matched the history. After all, why should anyone care what Sherlock Holmes learns in America in 1865 if I’ve made up the history of that period? AndCivil War “buffs” in particular are notoriously picky — as am I! Meanwhile, I visited all the key sites, including the old DuPont gunpowder works (now the Hagley Museum in Wilmington), Ford’s Theater, Petersburg and Richmond, the major battlefields and of course Booth’s escape route through Maryland (many times). As the story came together, I triple-checked dates and events, all the while compressing the action, because Booth was on the run for 12 days, with 5 of those days spent hiding in a pine thicket, and I didn’t want to lose the reader by describing every minute of days when nothing happened — while staying true to the timeline.

Can you explain how you keep your writing realistic but also fun and fictitious.

It starts with the voice. Sherlock Holmes has a distinctive voice — very different from Dr. Watson, who narrates half of my book — and Holmes’s is a wonderful voice to write with, because it is didactic and precise, not flowery or Victorian, but with a keen sense of humor. Watson’s voice is fun to write, too — stuffy, more conventional, but with a great sense of story. So long as I kept those voices in my head the action stayed lively and true (something I learned the hard way when, after completing the book for the first time, my inner English student took over and I spent a good three months trying to pare down the number of pages until I realized everything I’d re-written was worse, and quite boring. When I brought back Holmes’s chatty, precise voice, and Watson’s more formal but evocative tone, the story came back.

What are you working on now?

Sherlock Holmes and the Great Game, which answers the question of what Holmes was doing during the three years he was presumed dead following his struggle with Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls in 1891. All we are told in the original stories is that he journeyed incognito to Florence, then Tibet (where he paid a visit to the Dalai Lama), then Mecca and Sudan before making his way to France and finally returning to London. That’s quite an itinerary, don’t you think? It suggests a spiritual journey as well as a physical one, and I’ve always felt it merited unearthing the true story of those travels (what did Sherlock Holmes discuss with the Dalai Lama???) As it happens, they occurred during a period when the Tsar was attempting to extend Russian influence south into Tibet, which of course Great Britain viewed as a direct threat to the Crown’s hold on India — a diplomatic chess match known as “the Great Game.” Hence, Sherlock Holmes and the Great Game.

Meet J. Lawrence Matthews

J. Lawrence Matthews has contributed fiction to the New York Times and NPR and is the author of three non-fiction books as Jeff Matthews. “One Must Tell the Bees” is his first novel. Written at a time when American history is being scrutinized and recast in the light of 21st Century mores, this fast-paced account of Sherlock Holmes’s visit to America during the final year of the Civil War illuminates the profound impact of Abraham Lincoln and his Emancipation Proclamation on slavery, the war and America itself. Matthews is now researching the sequel, which takes place a bit further afield—in Florence, Mecca and Tibet—but readers may contact him at jlawrencematthews@gmail.com. Those interested in the history behind “One Must Tell the Bees” will find it at jlawrencematthews.com.

Connect with Lawence

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jlawrencematthewsauthor

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JLawrenceMatth1