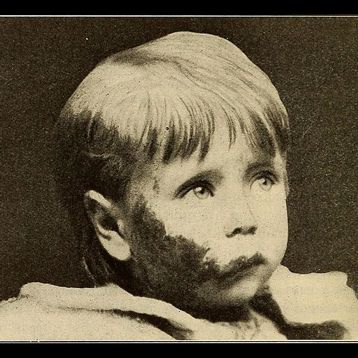

A boy with his head in the clouds. A man with a head full of dreams.1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child. Cut off from each other, there is no opportunity for husband and wife to teach each other the language of their loss. By the time they meet again, the subject is taboo. But unspoken grief is a dangerous enemy. It bides its time. A decade later and now a successful businessman, Robert decides to create a pleasure garden in memory of his sons, in the very same place he found refuge as a boy–a disused chalk quarry in Surrey’s Carshalton. But instead of sharing his vision with his wife, he widens the gulf between them by keeping her in the dark. It is another woman who translates his dreams. An obscure yet talented artist called Florence Hoddy, who lives alone with her unmarried brother, painting only what she sees from her window..

Scarlet Fever’s Terrible Toll

Addressing the British Association at Liverpool, Professor Huxley stated that during the years 1863, 1864, and 1869, scarlet fever (also known as Scarletina) claimed the lives of no fewer than 90,000 persons. When in 2016, scarlet fever was seen to be making ‘a come-back’, newspaper headlines referred to ‘The Victorian Disease’ – and with good reason.

The major outbreak in England and Wales took place during the years 1825–1885, with high levels of mortality. Germ theory was still in its infancy. Prior to its development, it was commonly held that disease was caused by miasma or ‘bad air’. Now the suggestion put forward was that poisonous matter passing from the diseased body ‘was capable of retaining vitality for a very long time, and of producing in another body a similar disease to that existing in the body from which it was derived.’ The first use of word ‘bacteria’ was by the German naturalist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, taken from the Greek baktḗria, meaning ‘little stick’, but to the majority bacteria and poison were one and the same.

In 1870, a correspondent identified only as ‘T F, Blencowe’ wrote a long letter to the Penrith Observer, certain in his conviction that poor quality housing was to blame for the prevalence of scarlet fever throughout England and Wales and describing the state of affairs as ‘a disgrace to the enlightenment of the 19th century…’ Certainly, epidemics were seen to be the direct result of city dwelling, and this was a time of rapid urbanisation. In Victorian Liverpool, one child in every four did not live to see its first birthday.

That germs were invisible was problematic. And for many, living in cramped quarters, the idea that the child affected should be ‘kept in a large room, and separated from the rest of the family’ was as laughable as Blencowe’s advice to pay attention to ventilation and cleanliness.

‘There are antidotes as invisible in their effects as they are themselves. These are what are usually called disinfectants, of which the most common are carbolic acid and Coady’s Fluid.’

Even those higher up the social ladder were not immune. In 1856, Archibald Tait (later to become the first Scottish Archbishop of Canterbury) lost five children to scarlet fever in as many weeks. In the same decade, Charles Darwin lost two of his children to the disease, first, his beloved ten-year-old daughter Annie in 1851, and in July 1858, his 18-month-old son, Charles Waring.

The first visible sign of the disease is a rash of tiny red bumps, sandpapery in texture, often on the chest and stomach – but bear in mind that this will be day two of the disease. Perhaps the child’s cheeks will be flushed. They may complaint or a sore throat, and there may be fever – symptoms so similar to those of teething that parents can be forgiven for mistaking one for the other. And this is exactly what Robert Cooke does:

***

When Robert passes the open door of the children’s nursery, he sees his wife’s face captured in a small halo of candlelight. The flame flickers and the halo shifts, revealing that she is bent over the boys’ cot-bed, a hand laid over Thomas’s brow. “I know,” she’s saying. “I know.”

He stands in the doorway, unseen, and watches her. Freya is a natural in the role of mother while, as head of the house, Robert often feels like an actor miscast, knowing that his understudy would be more suited to the part. But as natural a mother as his wife is, Robert worries that the children will grow accustomed to her sitting with them until they fall asleep, and will not remember how to do it without her soft lowing and her lullabies. “Come down to supper,” he says in a low voice.

Freya looks up. He sees now that she is anxious. “Thomas has a fever. I think we ought to send for Dr Stanbury.”

The doctor won’t thank them for disturbing his evening for the sake of milk teeth. Besides, they’ve been here before. When their daughter Estelle was teething she would get herself all hot and bothered. “Let’s take a look at you, little man.” (Here is a line Robert can say with authority.) He collects the second candlestick from the mantel. The flame dances as he crosses the room to inspect his son. Thomas is grizzling, his skin pale with red blotches on his cheeks. His thumb is anchored in his mouth, splayed fingers glistening with drool. Robert crouches down to better see, and the shadow of his wife’s head and shoulders rises up the wall, a dark guardian angel.

“Are your teeth troubling you?” At two years old, the boy already has his incisors. Robert prises Thomas’s wet thumb from his mouth and feels along his gum – Freya’s right, the boy’s cheeks are livid. The moment Robert feels the sharp point of a tooth poking through, Thomas pulls away and whimpers. “There it is, right at the back. A molar.”

***

Seen in candlelight, Robert may have overlooked the appearance of his son’s tongue, which may have been ‘covered with a white fur, through which appear little red papillae or points, giving the appearance described as the strawberry tongue. In the years before the discovery of penicillin and the mass production of anti-biotics, what could a doctor do?

The doctor came with his Epsom salts and his razor to shave their poor heads, but no amount of cool rags could soothe them. In the end it just seemed to be something to keep Robert occupied while Freya was instructed to keep her distance. (At least he’d insisted on that.) ‘Change the rags,’ Dr Stanbury said. ‘See if they won’t take a little broth.’

He might also have administered ammonia, carbonate or nitrate silver, all thought to have properties that might counteract the poison from the fever.

A Victorian edition of Domestic Medicine has a recipe for ‘a very good mixture for the first few days of the disease is the following:-

Chlorate of potash… … … 1 drachm.

Spirits of nitre … … … 1 drachm.

Simple syrup … … … 4 drachms.

Water … … … … 4 ounces

Mix one table-spoonful every four hours in as much water. For children below four years, a dessert-spoonful.’

If patients made it past the ninth day, hopes of recovery started to increase. The rash faded and the skin (and sometimes the tongue) will peel as if had suffered sunburn. But, like Cooke’s sons, many young children were not so lucky. Robert Cooke might have been forgiven for his mistake. The question is, would he be able to forgive himself?

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B09X61J6PR

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B09X61J6PR

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B09X61J6PR

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B09X61J6PR

Barnes and Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/small-eden-jane-davis/1141322156

Waterstones: https://www.waterstones.com/book/small-eden/jane-davis/9781838034825 (POD): https://www.waterstones.com/book/small-eden/jane-davis/9781838034818 (Tradepaperback)

Foyles: https://www.foyles.co.uk/witem/fiction-poetry/small-eden-gambles-sometimes-pay-off-a,jane-davis-9781838034818

Kobo: https://www.kobo.com/gb/en/ebook/small-eden

iBooks: https://books.apple.com/gb/book/small-eden/id1617742505

Smashwords: https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/1142088

Meet Jane Davis

Hailed by The Bookseller as ‘One to Watch’, Jane Davis writes thought-provoking literarypage turners.She spent her twenties and the first half of her thirties chasing promotions in the businessworld but,frustrated by the lack of a creative outlet, she turned to writing.

Her first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

Interested in how people behave under pressure, Jane introduces her characters when they are in highly volatile situations and then, in her words, she throws them to the lions. The the mess he explores are diverse, ranging from pioneering female photographers, to relatives seeking justice for the victims of a fictional disaster.

Jane Davis lives in Carshalton, Surrey, in what was originally the ticket office for a Victorian pleasure gardens, known locally as ‘the gingerbread house’. Her house frequently features in her fiction. In fact, she burnt it to the ground in the opening chapter of ‘An Unknown Woman’. In her latest release, Small Eden, she asks the question why one man would choose to open a pleasure gardens at a time when so many others were facing bankruptcy? When she isn’t writing, you may spot Jane disappearing up the side of a mountain with a camera in hand.

Connect with Jane

Website: https://jane-davis.co.uk

Twitter: https://twitter.com/janedavisauthor

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JaneDavisAuthorPage

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jane-davis-b1159563/

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/janeeleanordavi

Book Bub: https://www.bookbub.com/profile/jane-davis

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Jane-Davis/e/B0034P156Q

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/6869939.Jane_Davis