London, 1578

William Constable is a scholar of mathematics, astrology and practices as a physician. He receives an unexpected summons to the Queen’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham in the middle of the night. He fears for his life when he spies the tortured body of an old friend in the palace precincts.

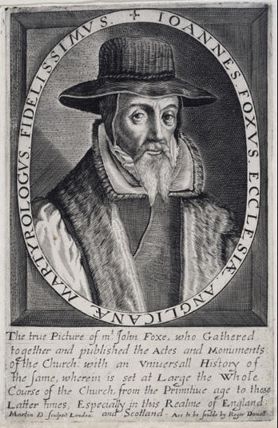

His meeting with Walsingham takes an unexpected turn when he is charged to assist a renowned Puritan, John Foxe, in uncovering the secrets of a mysterious cabinet containing an astrological chart and coded message. Together, these claim Elizabeth has a hidden, illegitimate child (an “unknowing maid”) who will be declared to the masses and serve as the focus for an invasion.

Constable is swept up in the chase to uncover the identity of the plotters, unaware that he is also under suspicion. He schemes to gain the confidence of the adventurer John Hawkins and a rich merchant. Pressured into taking a role as court physician to pick up unguarded comments from nobles and others, he has become a reluctant intelligencer for Walsingham.

Do the stars and cipher speak true, or is there some other malign intent in the complex web of scheming?

Constable must race to unravel the threads of political manoeuvring for power before a new-found love and perhaps his own life are forfeit.

Elizabethan Adventurers and Ship Navigation

State of Treason was half written when my writing veered away from its planned structure and took off in an unexpected direction. More than a minor diversion, I had to halt writing and research the background to this new sub-plot. I shouldn’t have been surprised. The book was an Elizabethan thriller set in 1578; a time when English privateers and merchants were planning and undertaking great adventures to the New Lands and raiding Spanish treasure ships. For reasons that I won’t divulge here, my protagonist, scholar and physician William Constable, is caught up in the preparation for one such venture.

The financier for the venture was a fictitious merchant, while the leaders were real historical figures, John Hawkins and Humphrey Gilbert. Hawkins was an adventurer, ship’s captain and ultimately an Admiral who was second in command in the battle against the Spanish Armada. He is known as one of the first slave traders and a pioneer of ‘triangular trade’. This involved capturing or buying slaves in West Africa, sailing across the Atlantic to Spanish settlements and trading slaves for sugar and molasses, which were then sold back in Europe at great profit. Hawkins was also inventive as a ship builder and it was largely down to him that the English navy built fast, efficient galleons. The overall impression I gathered of Hawkins was of a brave and intelligent man, but not an endearing one.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert was an adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier. He was noted for his cruelty during a military career in Ireland and courage as a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America. The historian A L Rowse described him as having, ‘… a questing and original mind, with the personal magnetism that went with it. People were apt to be both attracted and repelled by him, to follow his leadership and yet be mistrustful of him.’

Elizabethan adventurers were certainly brave. The ships they sailed were small, navigation was uncertain, but potential rewards were enormous. In 1578 Francis Drake was in the Pacific, mid-way into his circumnavigation, returning to Plymouth in 1580. The Queen’s half share of Drake’s treasure was more than enough to pay off the entire national debt. No wonder Drake got a knighthood.

A major part of my new research entailed a crash course on celestial navigation. I created William Constable as a mathematician and surveyor of the movement of the stars. In the past, he had worked with his mentor, Doctor Dee, on ways to improve navigation. The adventure, led by Hawkins and Gilbert, rekindles his interest and he sets to work developing an improved instrument of navigation.

The art of navigation developed rapidly in the sixteenth century in response to explorers who needed to find their positions without landmarks. Instruments were used to determine latitude, but longitude required accurate timepieces and these were not yet available. Instead, navigators used educated guesswork or ‘dead reckoning’ by measuring the heading and speed of the ship, the speeds of the ocean currents and drift of the ship, and the time spent on each heading.

A cross staff was in common use in the mid sixteenth century as an instrument to calculate latitude. This device resembled a Christian cross. The vertical piece, the transom or limb, slides along the staff so that the sun or star can be sighted over the upper edge of the transom while the horizon is aligned with the bottom edge. The major problem with the cross-staff was that the observer had to look in two directions at once – along the bottom of the transom to the horizon and along the top of the transom to the sun or the star. No mean feat on a rolling deck.

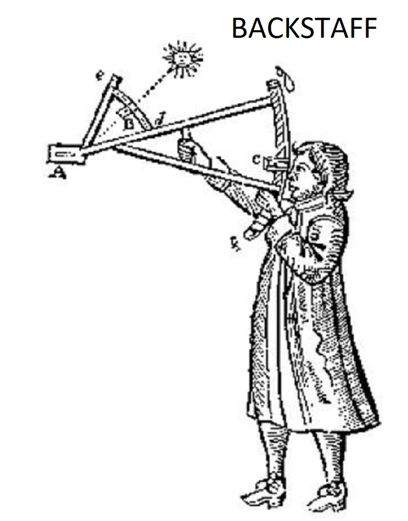

A more advanced instrument was the Davis Quadrant or backstaff. The observer determined the altitude of the sun by observing its shadow while simultaneously sighting the horizon. Captain John Davis conceived this instrument during his voyage to search for the Northwest Passage and is described in his book Seaman’s Secrets, 1594. One of the major advantages of the backstaff over the cross-staff was that the navigator had to look in only one direction to take the sight – through the slit in the horizon vane to the horizon while simultaneously aligning the shadow of the shadow vane with the slit in the horizon vane.

The shadow staff in the book, invented by William Constable, is an imagined forerunner of the backstaff.

Meet Paul Walker

Paul is married and lives in a village 30 miles north of London. Having worked in universities and run his own business, he is now a full-time writer of fiction and part-time director of an education trust. His writing in a garden shed is regularly disrupted by children and a growing number of grandchildren and dogs.

Paul writes historical fiction. He inherited his love of British history and historical fiction from his mother, who was an avid member of Richard III Society. The William Constable series of historical thrillers is based around real characters and events in the late sixteenth century. The first three books in the series are State of Treason; A Necessary Killing; and The Queen’s Devil. He promises more will follow.

Connect with Paul

Website: https://paulwalkerauthor.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PWalkerauthor

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Paul-Walker-Author-113027670552556

My thanks also, Mercedes. Having read the post again, I think it could benefit from a couple of diagrams. Sorry, should have thought of that.

Such an interesting post.

Thank you so much for hosting today’s tour stop.