Step back in time to the exhilarating days of the 1863 Gold Rush in Melbourne and the bustling northern gold towns like Ballarat and Bendigo in “The Case of the Wandering Corpse.” Get ready for a gripping journey into the heart of this historical mystery, where the past meets intrigue, and two compelling characters, Findo Gask and Erroll Rait, are your guides.

The year is 1863, and Melbourne is a hotbed of opportunity and danger. The promise of gold lures prospectors from far and wide, turning the city into a melting pot of ambition and a breeding ground for crime. In this intoxicating backdrop, “The Case of the Wandering Corpse” unfolds.

Findo Gask and Erroll Rait, our intriguing duo of protagonists, are drawn into a web of intrigue when they stumble upon a man wrongly accused of murder. Fueled by their unyielding sense of justice, they embark on a journey to set things right, but little do they know that their quest will lead them into the treacherous heart of an unscrupulous secret criminal society.

As they race against time to exonerate the innocent man, Findo and Erroll find themselves entangled with a shadowy and malevolent secret society that is spreading its sinister tentacles throughout Melbourne. This society, known for its ruthlessness, will stop at nothing, even murder, to achieve its dark goals. And at the heart of those goals lies an obsession: the location of a hidden hoard of gold stolen from a daring robbery years earlier.

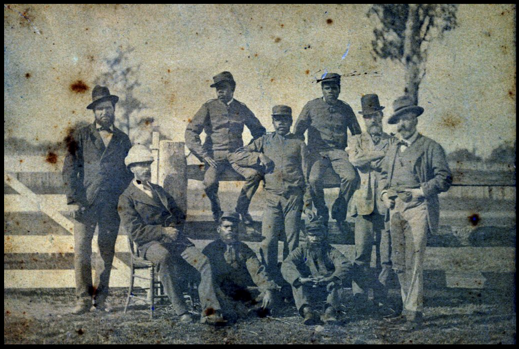

Antipodean Justice: The evolution of law and order in the colonies

(Queensland Police Service) 2018

My research into the development of Australia for my stories, partly set in 1800s Melbourne, unveiled a colonial police force that had many flaws; the paradox of the drive for order and justice contrasted with the flawed implementation of this policy as the nation grew. The event that began the infamous Ned Kelly saga stands out as one example (although, full disclosure; there are many conflicting stories about the incident).

The trigger was the actions of one Constable Fitzpatrick who, on his own initiative sought to arrest Ned’s brother, Dan, for horse theft. Dan demands to see an arrest warrant, which Fitzpatrick did not have and then Fitzpatrick, probably drunk having visited a bar for some brandy beforehand[1], crosses the line, attempting to force himself on Ned’s 15-year-old sister, Kate[2].

There is a scuffle but Ellen Kelly, the family matriarch, manages to calm things down. However, upon returning to his station, Fitzpatrick falsely claims that Ned fired at him three times and that Ellen struck him with a shovel. Consequently, Ellen was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison, with her newborn child in tow (Fitzpatrick would eventually be dismissed from the force)[3].

Unsurprisingly, the evolution of the Australian police force shared similarities with its British counterpart. In 1829, Sir Robert Peel’s principles for officer recruitment in England emphasized young, working-class, literate men at least 5’ 7” tall with no criminal history (although this ideal fell short with 80% of the inaugural recruits resigning or being dismissed within their first year for various misconduct, mostly drunkenness)[4]. In Australia, with a significant population of freed, transported convicts forming the core of the police force, Peel’s idealistic standards also proved unachievable[5].

In 1825, efforts began to centralize the police forces in New South Wales, aiming to make them more professional[6]. However, this faced resistance, mirroring sentiments in England that such centralization would infringe on traditional British freedoms. Francis Rossi, the new Police Commissioner, also faced allegations of corruption as a magistrate in 1826[7] and opposition to centralization in rural communities came from the rural gentry and local magistrates who guarded their powers jealously[8]. That is until 1851, when Victoria also became an independent colony, leading to the birth of the Melbourne police force, bolstered by officers imported from London’s Metropolitan Police.

By the mid-19th century, the colonial constabulary in Australia had a less-than-stellar reputation, viewed with suspicion by the very people they were meant to protect and govern[9]. Policing the convict and criminal population was considered a low-status, poorly compensated profession. Coupled with a colonial government that levied taxes without providing adequate services, and allegations of nepotism and corruption[10], it’s no surprise that the police were both feared and disrespected.

This tumultuous relationship between miners and the police in the gold-rich Victoria region ignited a significant moment in Australian history. The oppressive policing methods, coupled with excessive taxation on miners, led to the Eureka Stockade rebellion on December 3, 1854. This was ruthlessly crushed but public anger led to several changes and is related in my novel “The Helots’ Tale, Redemption”.

With my fictional detectives set in Melbourne, I looked particularly at this city. In its quest to combat crime, an autonomous detective force was formed, but its effectiveness was questionable. A magistrate, for example, concerned with bribery, expressed concerns about a “most suspicious suddenness in getting rich”[11] among the detective force. By the 1880s, corruption within the Melbourne Detective Force had become a public scandal. Detectives faced harsh criticism for their questionable information-gathering methods and lack of accountability, leading to the eventual disbandment of the unit.

This unsettling climate provided a backdrop for my amateur detectives in the Major Findo Gask and Errol Rait Mysteries series. These characters, while working in concert with the police, are acutely aware of the potential for misconduct and frequently follow their instincts down alternative paths. They also encounter Captain Frederick Standish, the third chief commissioner of police in Melbourne from 1858 to 1880, a man whose notorious gambling habits and corrupt practices stained the police force’s reputation[12]. Yet, he somehow managed to still become a prominent figure in society.

And so we find ourselves circling back to the infamous Ned Kelly gang. Captain Standish was at the helm during the extended pursuit of these notorious bushrangers but his handling of the chase and the violent conclusion saw him resign shortly thereafter.

In retracing the tumultuous history of Australian policing, one thing is abundantly clear: it was a world rife with contradictions, where the line between law and lawlessness was often blurred. While Ned Kelly’s legend looms large, the equally compelling saga of those who worked to deliver justice in the roaring Antipodean gold fields remains an enthralling narrative in its own right.

As I continue to write and excavate the hidden layers of history, I am reminded that the past, with all its characters, complexities, and controversies, provides the richest material for storytelling.

[1] Kieza, Grantlee (2017). Mrs Kelly.

[2] In 1929 journalist J.J. Kenneally gave this version of the incident based on interviews with the remaining Kelly brother, Jim, and Kelly cousin Tom Lloyd.

[3] https://www.ironoutlaw.com/keep-ya-powder-dry/the-fitzpatrick-conspiracy/

[4] Of the first 2,800 new policemen only 600 managed to keep their jobs. https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/the-metropolitan-police-its-creation-and-records-of-service/

[5] In 1828, only 13 per cent of the population were free immigrants. https://rune.une.edu.au/web/bitstream/1959.11/3155/5/open/SOURCE04.pdf

[6] Rossi reorganised the Sydney police on a system somewhat similar to that of the Bow Street office in London, although continuously hampered by inadequate funds and recruits of poor quality. https://www.australianpolice.com.au/francis-nicholas-rossi/

[7] Rossi was involved in a local scandal when allegations of malpractice were brought against him in the Supreme Court in 1826. The chief justice absolved Rossi from corrupt motives, but because his conduct had been irregular he was not allowed costs. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rossi-francis-nicholas-2610

[8] https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rossi-francis-nicholas-2610

[9] Report from the First Police Magistrate of Sydney in Appendix to Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Select Committee on Police and Gaols, 1 May 1835, (New South Wales Legislative Council, Votes and Proceedings), p. 361. 9 LOC

[10] See ‘The History of Corruption within Victoria, Australia’ by Samantha Perussich

[11] https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01154b.htm

[12] His conduct of the police operations was, according to the 1881 royal commission on the police, ‘not characterized either by good judgment, or by that zeal for the interests of the public service which should have distinguished an officer in his position’. Australian Dictionary of Biography

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Case-Wandering-Corpse-Erroll-Mysteries/dp/0645340693/

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Case-Wandering-Corpse-Erroll-Mysteries/dp/0645340693/

Meet David Cairns of Finavon

David Cairns of Finavon was, until recently, a technology entrepreneur. He has lived and worked on four continents and, after many years making his home in the Perthshire highlands, these days makes he stays on the Gold Coast with his Australian wife. He is the author of The Helots’ Tale series – Downfall and Redemption – and the Gask and Rait Mysteries series. His latest novel The Case of the Wandering Corpse (Finavon Press, £9.99, is available from all good book retailers) www.CairnsofFinavon.com

Visit David on Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheDavidCairns