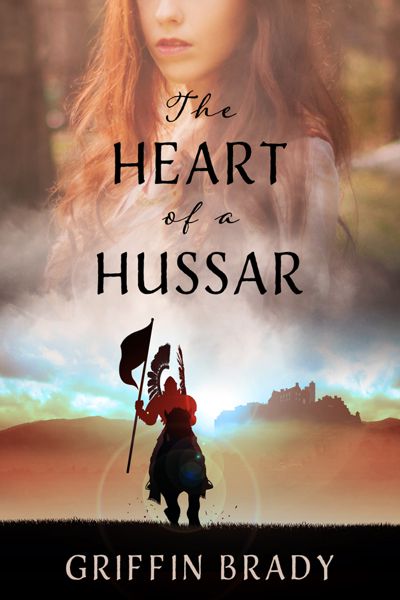

Poland is at war. He must choose between his lifelong ambition and his heart.

Exploiting Muscovy’s Time of Troubles, Poland has invaded the chaotic country. Twenty-two-year-old Jacek Dąbrowski is an honorable, ferocious warrior in a company of winged hussars—an unrivaled, lethal cavalry. When his lieutenant dies in battle, Jacek is promoted to replace him, against the wishes of his superior, Mateusz, who now has more reason to eliminate him.

Jacek dedicates his life to gaining the king’s recognition and manor lands of his own. Consequently, he closely guards his heart, avoiding lasting romantic entanglements. Unscathed on the battlefield, undefeated in tournaments, and adored by women eager to share his bed, Jacek has never lost at anything he sets out to conquer. So when he charges toward his goals, he believes nothing stands in his way.

Upon his return from battle, Jacek deviates from his ordinarily unemotional mindset and rescues enemy siblings, fifteen-year-old Oliwia and her younger brother, Filip, from their devastated Muscovite village. His act of mercy sets into motion unstoppable consequences that ripple through his well-ordered life for years to come—and causes him to irretrievably lose his heart.

Oliwia has her own single-minded drive: to protect her young brother. Her determination and self-sacrifice lead her to adopt a new country, a new religion, and a new way of life. But it’s not the first time the resilient beauty has had to remake herself, for she is not what she appears to be.

As Jacek battles the Muscovites and Tatars threatening Poland’s borders for months at a time, Oliwia is groomed for a purpose concealed from her. All the while, Mateusz’s treachery and a mysterious enemy looming on the horizon threaten to destroy everything Jacek holds dear.

The Polish Winged Hussars

Europe’s 16th century was a time of transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, and in the Kingdom of Poland, it was an era marked by cultural enlightenment, democracy, and religious freedom—a golden time. But it was not a peaceful one, nor would it be. It was during this age that an elite group of armored cavalrymen known as the “Polish winged hussars” evolved and were recast as a jaw-dropping fighting force that would impact warfare for centuries to come. Exceptionally trained noblemen, the hussars were highly skilled shock troops. They were the Polish Renaissance version of modern day special forces, and they were formidable.

They are referred to by varying labels, including (but not limited to) husaria, towarzysze husarska, heavy hussars, heavy lancers, and winged lancers.

In 1569, the Kingdom of Poland formally united with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (the “Commonwealth”). With an area spanning over 400,000 square miles and a population of eleven million, it was one of the largest countries in Europe.

The Commonwealth shared a king and their parliaments—the Sejm—and though their armies were similarly structured, they were fielded separately. Soon after the formation of the Commonwealth, the Polish winged hussar became a fundamental component of its fighting force.

The hussar was a complex amalgam of eastern and western influences. While Polish armies had been based on western Europe’s medieval knight—complete with cumbersome armor and heavy lance—Lithuania’s military borrowed from Byzantine, Russian and Mongol traditions. The first hussars to appear were unarmored Serbian light cavalry with shields, and their force soon grew to include Polish, Lithuanian and Hungarian recruits. In the 1550s, companies were a mishmash—a mix of heavily-armored, western style lancers and the lighter hussar cavalrymen who sometimes sported western armor as they fought alongside the heavy lancers.

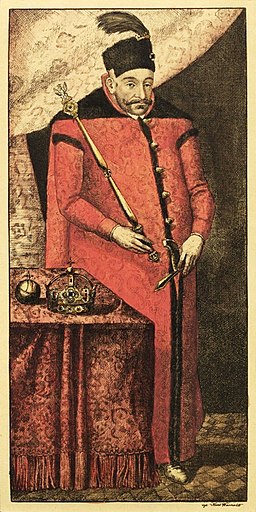

Not until the election of King Stefan Batory in 1576 did these two forces blend together in one consistent “heavy” cavalry, abandoning the shield and taking up armor in its stead. King Stefan’s newly created heavy hussars were soon battle-tested and proved themselves a dominant force, and by the 1590s, the prototype was consistent throughout the Polish army.

The Commonwealth was perpetually scuffling with its neighbors. Land grabs see-sawed back and forth, and borders shifted and changed as one country seized the territory of another only to give it up again. The Commonwealth’s holdings from the 15th to the 18th centuries were vast, and it exercised its right to protect its borders and its people through a strong military presence. Cossacks and Russians threatened its eastern border; Sweden swept in from the north; Crimean Tatars raided across the southeastern edge while the Ottoman Empire was expanding its territory northward in a bid to conquer all of Christian Europe.

Unlike many of our modern-day armies, Poland fielded a small standing army. This permanent force, the “kwarciani,” was three to five-thousand strong, of which a thousand were hussars. The kwarciani were garrisoned mainly along the Commonwealth’s southeastern border to deter constant threats of invasion. When the need for a large force mounted in the face of war, a lêvée en masse was issued, and the King sent letters of recruitment to amass companies. A company was typically raised by a wealthy, landed nobleman, and he acted as their commander, their “rotamistrz.” His was a private company, and he fought alongside the warriors he recruited—also noblemen. Because the rotamistrz and the hussars he called forward had the wherewithal to cover the cost associated with such an endeavor, the Sejm did not have to scramble for funds at the outset. While the men did earn wages, their expenses often outstripped their pay. These noblemen willingly answered the call because they were motivated by duty, love of country, and honor. They were said to have had one of the highest morales among Commonwealth troops.

This choice cavalry was defined by several distinct features. First was their mightiest weapon, a decorated wooden lance known as the kopia, which ranged from thirteen to twenty feet in length. Second was a set of “wings,” curved frames to which eagle and various feathers were attached. These were first worn on the backs of their saddles and later migrated to the backplates of their armor so the cavaliers appeared to have sprouted wings. Third was the charge used to destroy enemy lines. The winged hussars came in waves at their foes, the front row riding knee-to-knee while leveling their steel-tipped kopie at their enemies’ navels. They rode into their opponents with such speed and force that more than one adversary could wind up impaled on a single lance. Once a hussar broke his lance—usually on the first impact—he fell back to seize a fresh one and charge again, or he took up his saber and continued the attack.

Polish husaria banners were formed in the traditional chivalric manner of the medieval knights. These lancers came from the nobility class—the “szlachta”—because the expense of raising such a soldier was enormous. Hussars began training as young boys on family estates, with fathers placing sons on horseback early to teach them the fine art of horsemanship that would be so vital to their success. They were taught to wield sabers from an early age, followed by training with broadswords, lances, tucks, war hammers, bows, pistols, and daggers. Their most crucial skill was handling the unwieldy kopia while controlling their mighty war horses, and they were coached by masters who were often retired hussars hired by the noblemen.

Instruction wasn’t limited to the practice field. Amid drills and combat maneuvers, the young men learned subjects like mathematics and Latin, the language of the Polish noble class. They were educated, came from wealth, and were highly skilled warriors revered for their prowess, their bravery, and their ferocity. Their presence often made the difference between triumph and defeat, and history has marked battle after battle where victory was achieved in spite of vastly lopsided odds against their forces.

Each hussar provided his own horses, weapons and armor. In addition, he brought with him his camp servants, squires, and his retainers (known as “pacholiks”). This group of support staff, the retinue—or “poczet”—numbered from two to seven men in addition to the hussar they served. Provisions for men, horses and camp were brought in wagons, which were also paid for by each hussar. These units, the poczets, were the small building blocks of companies, which then united into regiments. The winged hussar’s defining weapon, his kopia, was furnished by the King. It was the only article the hussar did not pay for himself.

In preparation for battle, the cavaliers outfitted themselves in dazzling fashion. The more lavish, the better. They typically wore short coats, known as żupans, in brilliant crimson beneath brass or gold-embellished steel armor. Leather boots in yellow or red were common, as were a variety of silk-lined animal pelts worn like capes. Helmets were often adorned with feathers and gems. The hussars’ war horses, specially bred Polish-Arabians, were their greatest—and most costly—asset, and were bedecked in sumptuous trappings that mirrored their owners’ raiment. The richness of the hussars’ accoutrements bespoke their wealth, and they took great pride in their appearance as they met the enemy on the battlefield.

Their tactics were highly effective on open ground, as documented in reports that still survive today. Narratives recount the decimation of an enemy’s front line after sustaining only one or two of the hussars’ impressive charges. The sight of a wall of armored cavalrymen clad in animal pelts riding at an enemy full out with leveled lances was terrifying and spectacular. Whether the wings added to the adverse psychological effect has been greatly debated, but certainly they did not lessen the intimidating visual impact wrought by such a charge, and they no doubt enhanced its magnificence. They are now the stuff of legends.

The history of this time and these valiant men is rich and worthy of telling, and will hopefully spur readers to investigate further. The Polish winged hussars flexed their formidable muscle for over a hundred years, garnering respect and dread from those familiar with their feats. But they were by no means superheroes, but they were larger than life: courageous, ferocious, skilled, proud warriors with a fierce love of country. They were also chivalrous, religious, and prided themselves on a high code of moral conduct. They were the modern knights of their time.

The Heart of a Hussar opens at the conclusion of one of their most extraordinary victories, the Battle of Kłuszyn, Russia, on July 4, 1610. A force of roughly 2,700 took on—and defeated—40,000* combined Russian and foreign troops in a conflict that lasted five hours. The Commonwealth forces had marched throughout the night, and took up the campaign when they arrived at first light. Of the 2,700, some 2,500 were Polish winged hussars, and the rest were infantry.

The astonishing fact about this battle is that it was not just one aberrant phenomenon. During the winged hussars’ “golden age,” from the late 16th century to the late 17th century, they engaged in similarly skewed battles where they emerged the victors. The difference in troop sizes was eye-popping, and yet they prevailed.

Polish winged hussars were truly exceptional warriors, and they played a vital in the Commonwealth’s success.

________________________

*As recounted in Radisław Sikora, Ph.D.’s writings. Dr. Sikora is one of the world’s leading experts on the history of the Polish winged hussars.

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B08HJQBHP2

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08HJQBHP2

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B08HJQBHP2

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B08HJQBHP2

This novel is available on #KindleUnlimited

Meet Griffin Brady

Griffin Brady is a historical fiction author with a keen interest in the Polish Winged Hussars of the 16th and 17th centuries. She is a member of the Historical Novel Society and Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. The Heart of a Hussar took third place in the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ 2018 Colorado Gold Contest and was a finalist in the Northern Colorado Writers’ 2017 Top of the Mountain Award.

The proud mother three grown sons, she lives in Colorado with her husband. She is also an award-winning, Amazon bestselling romance author who writes under the pen name G.K. Brady.

Connect with Griffin

Website: https://www.griffin-brady.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/griffbrady1588

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AuthorGriffinBrady

BookBub: https://www.bookbub.com/profile/griffin-brady

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/author/griffinbrady

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/20675881.Griffin_Brady

Thank you so much for featuring the book!

Such an interesting post.

Thank you so much for hosting today’s tour stop for The Heart of a Hussar.

All the best,

Mary Anne

The Coffee Pot Book Club