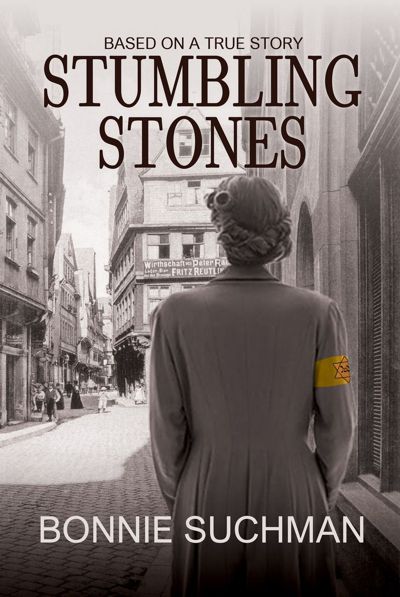

Shortlisted for the Hawthorn Prize 2024

“Alice knew that Selma sometimes felt judged by their mother and didn’t always like it when Alice was praised and Selma was not. Alice glanced over at her sister, but Selma was smiling at Alice. In what Alice understood might be Selma’s last act of generosity towards her sister, Selma was going to let Alice bask in the glow of Emma’s pride toward her elder daughter. Then the three shared a hug, a hug that seemed to last forever.”

Alice Heppenheimer, born into a prosperous German Jewish family around the turn of the twentieth century, comes of age at a time of growing opportunities for women.

So, when she turns 21 years old, she convinces her strict family to allow her to attend art school, and then pursues a career in women’s fashion. Alice prospers in her career and settles into married life, but she could not anticipate a Nazi Germany, where simply being Jewish has become an existential threat. Stumbling Stones is a novel based on the true story of a woman driven to achieve at a time of persecution and hatred, and who is reluctant to leave the only home she has ever known.

But as strong and resilient as Alice is, she now faces the ultimate challenge – will she and her husband be able to escape Nazi Germany or have they waited too long to leave?

Why Didn’t They Leave?

Understanding the Challenges for Jews Fleeing Nazi Germany

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Jews represented less than one percent of the German population. Yet, the Nazis made anti-Semitism a core component of their ideology and encouraged Jews to leave Germany. With all that we know about how the Jews were treated by the Nazis, one must wonder why German Jews didn’t leave in 1933. The answer to this question is complicated, which is one of the reasons why I wrote Stumbling Stones.

When they first took power, the Nazis understood that any actions taken against the German Jewish population to encourage emigration would raise an immediate problem – Jews held great wealth in Germany and the sudden loss of capital could negatively impact an economy still reeling from the depression. In addition, early in his tenure, Adolf Hitler made the decision to rearm Germany, and Germany needed capital to pay for such armament.

To prevent Jewish capital flight, the Nazi government lowered the threshold for application of the Reich Flight Tax, which taxed all assets leaving Germany at a rate of 25 percent. Prospective emigrants were also required to move all of their money into a blocked account in a subsidiary of the Reichbank, to purchase foreign currency at a very unfavorable exchange rate, and then to have a 20% fee applied. These measures would have resulted in a loss of about half of the value of assets, so that German Jews of means tended to remain in Germany, at least in the early years of the Nazi regime. Instead, mostly young people or those with few assets chose to leave Germany.

For those who made the decision to leave, their options were limited. Most of those leaving Germany fled to a neighboring European country or to Palestine (which was Israel before independence in 1948). The US had in place restrictions on immigration, the most challenging of which was the “likely public charge” clause, which required that a financial sponsor be found for the potential immigrant. Mostly because of this clause, only 10% of the US quota for German immigration in 1933 was filled.

When Hitler first came to power in 1933, there were a number of anti-Semitic actions taken, but fearing that too many actions could jeopardize German foreign trade or damage the economic revival at home, there was a reduction in such actions in 1934. Moreover, there was concern that actions towards Jews could also jeopardize the Olympic Games that were to take place in Berlin in 1936. Because of this inconsistency in approach towards German Jews, many Jews opted to remain in Germany, hoping that 1933 was an anomaly and that conditions would improve.

A shift in approach to Germany’s Jew began in 1935 with the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws. These laws became the cornerstone for legalized persecution against German Jews. The Nuremberg Laws defined who was a Jew and then stripped all Jews of German citizenship, as well as prohibited marriages and extramarital sexual intercourse between Jews and non-Jews. These laws fueled the removal of Jews from German society. Many Jewish-owned businesses were pressured to close, and Jews were restricted in what employment they could hold. Many Jews lost their jobs as a result.

Moreover, Germany increased the pace of plunder. The fee assessed after the Reich Flight Tax was paid was increased to 68% in 1935 and 81% in 1936. And the Gestapo also became involved with Jewish emigration, working with the tax office to monitor emigration activity. Because of this collaboration, Jews who had announced that they were leaving found themselves subject to phony taxes and sometimes even arrest. By the time of Kristallnacht at the end of 1938, it was essentially impossible for Jews to leave Germany with any of their assets. Any German Jew leaving at that time could leave with just 10 Reichmarks, the equivalent of approximately fifty dollars.

For those German Jews who had opted to emigrate before Kristallnacht, finding a place to emigrate still remained a challenge. By 1937, 129,000 had left Germany, but 371,000 still remained. In 1936, just 25% of the US quota for Germans was reached, likely because of the “likely public charge” clause. And emigration to Palestine was curtailed beginning in 1936, so that, by 1939, virtually no German Jews were able to emigrate. The US government started to ease sponsorship requirements beginning in 1937, so that about half of the quota was reached that year. Only in 1939 was the quota fully reached, but, by this point, Jews on the waiting list would be waiting years for a spot.

Until 1938, measures taken by the Nazi were intended to limit the assets Jews could take with them, but measures after Kristallnacht actually inhibited Jewish emigration. In order to leave, Jews still needed the tax clearance certificate, but for many Jews, obtaining that certificate became increasingly difficult. The Nazi government assessed a new 25% levy on all Jews assets after Kristallnacht to cover the damage and cleanup costs of the pogrom. Not only was this an additional cost, but the levy was based on the value of the assets as of April of 1938. The plummeting value of Jewish assets after Kristallnacht made it impossible for many Jews to pay the levy, particularly for those who could not sell their property because it carried a Jewish stigma. And the appearance of phony taxes owed were preventing German Jews from receiving their tax clearance certificates. And complaining about those fake taxes made it even harder to clear their tax obligations. Some were even arrested after complaining about the phony taxes.

Those who could not clear their tax obligations were stuck in Germany, and the waiting list for US visas grew longer and longer, as those German Jews who were reluctant to leave finally saw the writing on the wall and decided to try to leave. But, by the middle of 1941, it was almost impossible to leave. When the German borders were finally closed in October 1941, 170,000 German Jews were still left in Germany. The Nazi government was then able to finally achieve its goal of total plunder of Jewish assets. The assets in all the blocked accounts were seized and the other assets left behind were confiscated, both from Jews who had successfully emigrated and from Jews who were ultimately deported.For a more in-depth analysis of the challenges faced by German Jews in escaping Nazi Germany, go to my website bonniesuchman.com.

Universal Buy Link: https://books2read.com/u/4ND1x8

Meet Bonnie Suchman

Bonnie Suchman is an attorney who has been practicing law for forty years. Using her legal skills, she researched her husband’s family’s 250-year history in Germany, and published a non-fiction book about the family, Broken Promises: The Story of a Jewish Family in Germany. Bonnie found one member of the family, Alice Heppenheimer, particularly compelling. Stumbling Stones tells Alice’s story. Bonnie has two adult children and lives in Maryland with her husband, Bruce.

Connect with Bonnie

Website: www.bonniesuchman.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BonnieSuchman

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61556457672565

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bonniesuchmanauthor/

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/bonniesuchman/

Book Bub: https://www.bookbub.com/authors/bonnie-suchman

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Bonnie-Suchman/author/B09L3BDVRQ

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/21796158.Bonnie_Suchman