Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, the man who would come to be known as El Cid, the Campeador, started out from modest origins. To look at him in his youth was perhaps to see a boy of no extraordinary quality. It was events later in his life that shaped him; his mastery of battle, his countless victories and loyalty to those who would so easily cast him aside then grovel for his return which attracted warriors to his side. But who was he, and where did he come from? Sifting through the limited sources we have, and sorting solid fact from fictitious legend, is a tricky task.

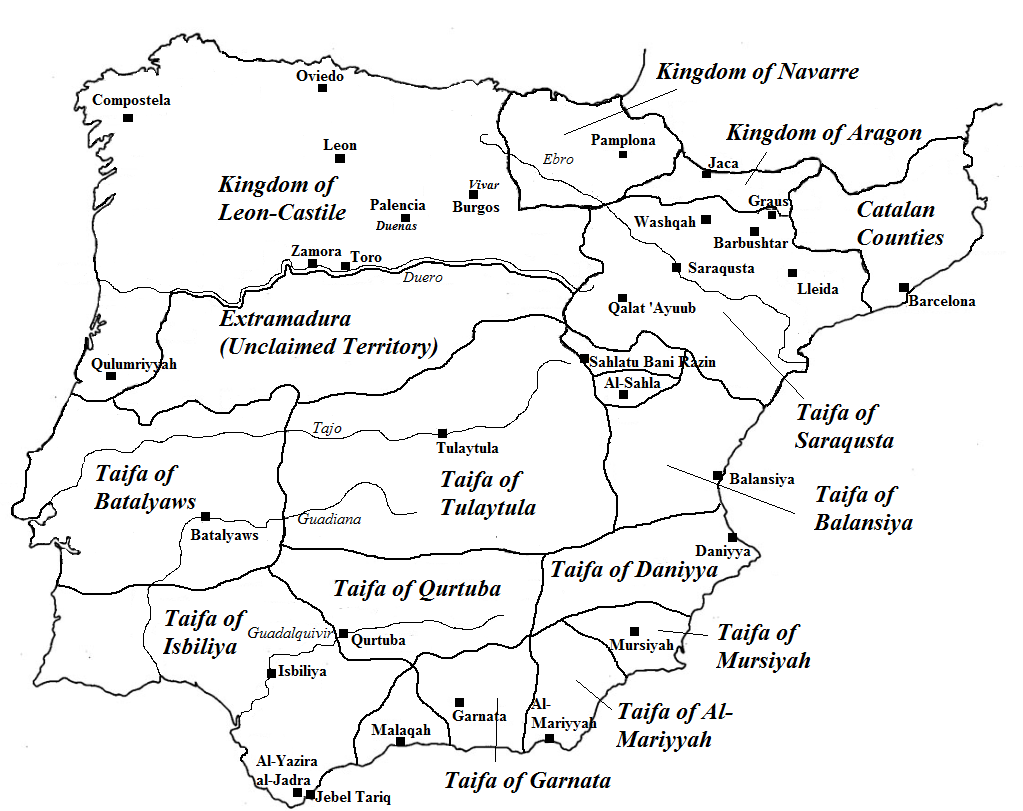

The generally accepted year of Rodrigo’s birth is 1043, though some scholars date it as early as 1041 and as late as 1050. His father was Diego Flaínez, who was perhaps one of the sons of a count of Leon, Flaín Muñoz, who ruled around the year 1000. Diego may have left his father’s estates to forge a name for himself as a caballero, or member of the lesser nobility who fought as knights in the employ of a lord. Evidence suggests he fought for King Fernando of Leon-Castile in a war against the Navarrese, perhaps in the battle of Atapuerca where Fernando slew the king of Navarre, his brother Garcia. For his service in liberating lands around Ubierna and Urgel, Diego was rewarded with estates at Vivar. But Diego never found the fame or fortune he desired, and he never frequented the court of the king. As for Rodrigo’s mother, scant is known. All we have is her lineage; she was the daughter of a lord Rodrigo Alvarez, who was a supporter of Fernando and was important enough to be present at his coronation, and her uncle was Muno Alvarez and held the castle of Amaya, to the north of Burgos.

The Song of the Campeador claims Rodrigo “is sprung from a more noble family, there is none older than it in Castile”. Whilst this is a clear exaggeration, his family did seem to have had some significant connections, and upon his ascendance in to adolescence Rodrigo found himself in Burgos, at the court of the infante Sancho. In what capacity is unknown, but it is possible Rodrigo may have squired for the infante himself, and that is where their close relationship could have originated; being a squire for a knight in Sancho’s employ is at the very least plausible. Rodrigo would have had a basic education before he went, with knowledge of history, a grasp of Latin and would have been taught to write by a member of the clergy acting as a tutor. In Burgos, he would have learned of the complex politics of the Iberian peninsula of the time; his body would have suffered the gruelling training regime of a squire, and would have been given lessons in the laws that governed the land.

As Spanish warfare at the time was primarily conducted from the saddle, confidence in horsemanship was a requirement for any sort of successful military career. By the age of seven Rodrigo would have learned to ride a mule, then advanced to a pony and finally a horse when he had matured and grown. Spanish horses were arguably the best in Europe, certainly the most sought after. At some point in his life Rodrigo came to possess a magnificent horse named Babieca. One of the legends states that it was a coming of age gift from his god father who was a Carthusian monk; the monk told the young Rodrigo he could choose any horse he desired, but when the young knight chose a horse his godfather deemed weak, he proclaimed “Babieca!” meaning “stupid”. Yet this seems highly unlikely, as the Carthusian order was not founded until 1084 in Germany, and did not spread to Spain until at least the twelfth century. It is likely a horse of Babieca’s stock came from the royal stables of a taifa, such as Seville, but there is no definitive date to the origin of the horse, nor Rodrigo’s acquisition of him.

The exact date of Rodrigo’s ascendency in to knighthood is also obscure, but it is believed he fought with Sancho at the battle of Graus in 1063; if we accept the date of birth from 1043, he would have been around the age of twenty. He would have received a belt from Sancho or even Fernando, the prime symbol that a man was worthy to serve as a member of the caballeros. The panoply of a knight of Leon and Castile at the time was a mix of Frankish influence from the north combined with the old Visigothic style: a long spear was the primary weapon on horseback, followed by long swords and even hand axes. For protection, chainmail hauberks with mail coifs or conical helms with long nose guards were used, though some knights preferred scale armour or hardened leather jerkins with iron rings sewn in to them. Whilst the Moors rode with shorter stirrups, so their knees were bent and allowed greater mobility on their swift steeds, Christian knights wore longer stirrups so they were almost standing as they rode, to give better control of spear and shield in the charge. Shields could be kite shaped or large and round for horsemen, yet small round bucklers were common when fighting on foot. The knights, at around forty strong per division, would ride side by side, so close their knees would almost touch, to form a wall of horseflesh and steel tipped spears coming for the enemy.

And it was this style of warfare El Cid would become accustomed to when he took to the field at Graus, and began his journey on the path to becoming a legend. The Historia Rodrici, one of our main sources for the Cid, claims “when Sancho went to Zaragoza and fought the Aragonese king Ramiro at Graus, whom he defeated and killed there, he took Rodrigo Diaz with him”. Trow suggests it was for his service at Graus that he was knighted by Sancho, but it is entirely plausible it could have occurred a little earlier, before the battle, for some other unnamed feat. The Historia could have been written in Catalonia, around the time El Cid was winning fame in his exile and carving a fiefdom of his own in the 1090s, and the specific reference to Graus in the same breath as Sancho’s victory highlights Rodrigo was responsible for some great deed during battle, and won great renown in the eyes of his peers. The Historia lists others great achievements, such as victory in single combat against Jimeno Garces, a champion of Navarre, and an unnamed champion of the Moors from Medinaceli, though there are not definitive dates for these conflicts.

If true, it shows that even from a young age, Rodrigo was a man unafraid to test himself against the very best warriors in the land. Soon the warriors of Castile would crown the young knight from Vivar with the moniker, Campeador: the champion.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Primary

The Historia Rodrici

Carmen Campidoctoris (Song of the Campeador)

Secondary

Fletcher, R (1989) The Quest for El Cid, Hutchinson: London

Reilly, B.F (1999) The Kingdom of León-Castilla under King Alfonso VI, 1065-1109, Princeton University Press: Library of Iberian Resources Online

Trow, M.J (2007) El Cid: The Making of a Legend, Sutton Publishing: Gloucestershire

Rise of a Champion: Legend of the Cid, Book 1

Antonio Perez is the son of a knight and a returning war hero, yet he loathes the idea of following in his father’s footsteps. But when his father is executed for alleged treason against Fernando, King of Leon-Castile, he launches a desperate bid to save his life and clear his name. Antonio soon learns that the world is much crueler and darker than he ever could have imagined.

Bereft of hope and condemned to slavery for his sins, he finds himself in the household of a young knight named Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, a man destined for greatness. Together, they must face their demons and put an end to the man responsible for the downfall of the fathers; known as Azarola, renowned for his fox like cunning and malice, and one of the most powerful lords of Leon.

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Rise-Champion-Legend-Cid-Book-ebook/dp/B08742YDMZ

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B08742YDMZ/

MEET STUART RIDGE

Stuart Rudge was born and raised in Middlesbrough, where he still lives. His love of history came from his father and uncle, both avid readers of history, and his love of table top war gaming and strategy video games. He studied Ancient History and Archaeology at Newcastle University, and has spent his fair share of time in muddy trenches, digging up treasure at Bamburgh Castle.

He has worked in the retail sector and volunteered in museums, before working in York Minster, which he considered the perfect office. His love of writing blossomed within the historic walls, and he knew there were stories within which had to be told. Despite a move in to the shipping and logistics sector (a far cry to what he hoped to ever do), his love of writing has only grown stronger.

Rise of a Champion is the first piece of work he has dared to share with the world. Before that came a novel about the Roman Republic and a Viking-themed fantasy series (which will likely never see the light of day, but served as good practise). He hopes to establish himself as a household name in the mound of Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, Ben Kane and Matthew Harffy, amongst a host of his favourite writers.

Website: www.stuartrudge.wordpress.com

Twitter: http://www.Twitter.com/stu_rudge

Facebook: http://www.Facebook.com/stuartrudgeauthor/

1 thought on “The Early Life of El Cid, Guest Post by Stuart Rudge”