Genonn’s tired and dreams of a remote roundhouse in the Cuala Mountains.

However, sudden rebellion in Roman Britain destroys that dream because the Elder Council task him with delivering Lorg Mór, the hammer of the Gods, to the tribes across the straits of Pwll Ceris. Despite being torn between a waning sense of duty and his desire to become a hermit, Genonn finally agrees to help.

When his daughter follows him into danger, it tests his resolve. He wants to do everything he can to see her back to Druid Island and her mother. This new test of will means he is once again conflicted between duty and desire. Ultimately, his sense of duty wins; is it the right decision? Has he done the right thing by relegating his daughter’s safety below his commitment to the clans?

Druids – who and what were they?

Druids are a contentious subject. Who were they? What was their role? How much of the sixteenth-century romanticists’ interpretation (take Merlin) is conjecture, and how much can be considered realistic? Aside from Archaeological evidence, all we know comes from Classical commentaries, specifically of Julius Caesar and Tacitus, but also of Strabo and Diodorus. The writing of Strabo and Diodorus so closely resemble those of Caesar it is likely there was some cross contamination between them. Caesar was the earliest to provide detail, so it is likely the others used him as a source.

Even the origin of the word itself is subject to disagreement. The modern term derives from the Latin druidae. However, ancient Classical writers said it came from a Gaulish word but were not specific. Some say it comes from the old Irish druí (sorcerer) or the old Welsh dryw (seer; wren). It could also derive from a proto-Celtic construct (hypothetical), druwides, meaning “oak-knower”.

We know little about their origins. Many believed druids existed throughout proto-Celtic Europe, from Ireland to Turkey (Anatolia), but modern archaeologists think it unlikely. Archaeological evidence points to them being native to Ireland, Britain, and Western France. Unlike popular belief that their religion revolved around stone circles, the Classical writers placed them in caves and sacred glades. That would tally with old ideas that the druids arrived with the Celts and were not associated with stone circles. However, there is evidence in the Paviland caves near Swansea that the druids were in Britain as many as twenty-six thousand years ago. Evidence in France (Lascaux) shows that druids might have existed seventeen thousand years ago.

None of these theories can be corroborated because very little has been written about druids. Although Caesar tells us of their literacy, they kept no written records of their practices because it would have contradicted their religious geis or taboos. Greeks referenced druids as early as the 4th century BCE. Still, the first detailed writings were from Caesar in the middle of the first century BCE.

What Caesar tells us in the Comentarii de Bello Gallico, his Gallic war history, is intriguing.

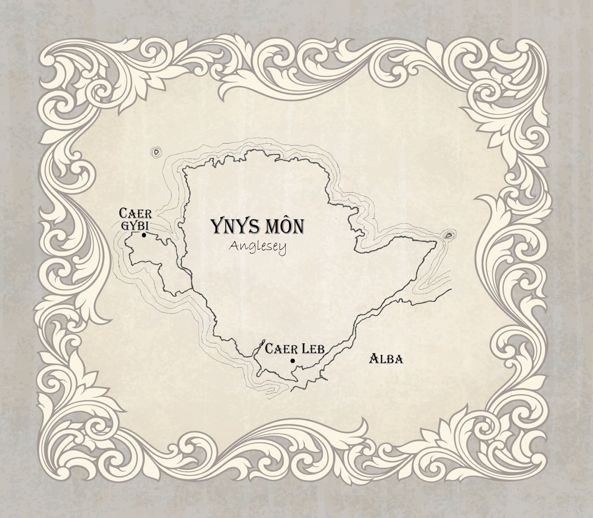

As well as philosophers, the druids were a powerful political force, but they also practised many professions, such as education, medicine, and law, and were advisers to kings and chieftains. Caesar tells us that they originated in Britain and hints that their influence continued to emanate from Britain into Gaul. Archaeological evidence suggests they had a power base in Anglesey, which would back Caesar’s theory.

He also touches on druidic centres of learning, telling us that they learnt their lore as a verbal tradition. Many believe the primary learning centre to have been on the island of Anglesey. Becoming a druid took as long as twenty years, so vast was the material they needed to learn.

“Magnum ibi numerum versuum ediscere dicuntur. Itaque annos nonnulli vicenos in disciplina permanent.”

– Comentarii De Bello Gallico by Julius Caesar

“They are said to learn a great number of verses, and therefore some remain under training for twenty years.” (Transliteration)

Caesar states that the primary religious doctrine of the druids was reincarnation. However, Tacitus also refers to the practice of sorcery during the first invasion of Anglesey, around 60 CE. The Fourteenth Legion crossing the Menai Straits were halted by witches and druidic spells.

“…while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair dishevelled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds.”

— The Annals of Imperial Rome by Cornelius Tacitus

As did others after him, Caesar claimed the druids performed human sacrifices, burning their victims while tied to wicker men. The victims were usually criminals, but when none were available, they would sacrifice ordinary citizens. He writes that because of their reincarnation beliefs, sacrifice would often be offering one soul in place of another at risk because of illness or battle. Modern historians think references to human sacrifice were nothing more than Roman propaganda. The reason is Romans often painted the conquered as savages. Romans thought themselves more civilised, considering sacrificing criminals to be barbaric but feeding them to lions, nothing more than entertainment for the masses. However, archaeological evidence shows that the druids did sacrifice humans, so it is difficult to know the truth.

Other Romans wrote about druids. For example, Pliny the Elder noted, “To murder a man was to do the act of highest devoutness and to eat his flesh was to secure the highest blessings of health.” These words, however, were obvious just embellishing what Caesar had already written.

That druids had a considerable influence over the Celtic clans is apparent. It was part of Roman imperialism to tolerate local laws and religions whenever possible. Not so the druids. After Romans suppressed them in Gaul under Tiberius, Claudius declared them outlaws in 54 CE, and Gaius Suetonius Paulinus invaded Anglesey to eradicate them. There can be only one reason why this persecution was considered necessary. Fear. The Boudiccan uprising meant that Suetonius failed. Agricola finally succeeded almost twenty years later, signalling the end of classical druidism.

Shortly after the advent of Christianity, the druids faded into obscurity, losing their priestly duties and becoming bards (filí). It is unclear if this obscurity is due to Roman persecution or Christianity’s spread. What is clear is that Christians assimilated many of the druid’s pagan rituals into Christian rites and festivals, such as moving Christ’s birth from spring to coincide with the Winter Solstice.

Modern desires have created much of druidism’s mythos, such as freemasonry is a direct descendant and that stone circles were central to druidic beliefs and making Myrddin (Merlin) a wizard with magical powers. There was a druidic revival in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries based more on that romantic conjecture than reality. Although we know little, Neo-Druidism takes inspiration from Classical accounts and romantic writers since the revival and archaeology and symbolism of proto-Druidic or pre-Druidic stone circles.

Hammer is available to read on #KindleUnlimited.

Universal Link: https://books2read.com/u/bzKZWz

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0BMLQML9J

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BMLQML9J

Amazon CA: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B0BMLQML9J

Amazon AU: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B0BMLQML9J

Meet Micheál Cladáin

Micheál has been an author for many years. He studied Classics and developed a love of Greek and Roman culture through those studies. In particular, he loved their mythologies. As well as a classical education, bedtime stories consisted of tales read from a great tome of Greek Mythology, and Micheál was destined to become a storyteller from those times.

Connect with Micheál

Website: www.philhughespublishing.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/cladain_m

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PerchedCrowPress

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/mickcladain/

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Miche%C3%A1l-Clad%C3%A1in/author/B07BGWK6BD

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/17189173.Miche_l_Clad_in

Thank you so much for hosting Micheál Cladáin today, with such a fascinating guest post. xx