Ireland 1652: In the desperate, final days of the English invasion of Ireland . . .

A fey young woman, Áine Callaghan, is the sole survivor of an attack by English marauders. When Irish soldier Niall O’Coneill discovers his own kin slaughtered in the same massacre, he vows to hunt down the men responsible. He takes Áine under his protection and together they reach the safety of an encampment held by the Irish forces in Tipperary.

Hardly a safe haven, the camp is rife with danger and intrigue. Áine is a stranger with the old stories stirring on her tongue and rumours follow her everywhere. The English cut off support to the brigade, and a traitor undermines the Irish cause, turning Niall from hunter to hunted.

When someone from Áine’s past arrives, her secrets boil to the surface—and she must slay her demons once and for all.

As the web of violence and treachery grows, Áine and Niall find solace in each other’s arms—but can their love survive long-buried secrets and the darkness of vengeance?

The Irish Resistance

One of the final chapters of the War of the Three Kingdoms, also known as the English Civil War, was the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland that started in 1649. England’s Parliament had been at war with King Charles I for the past seven years which ended in his execution on January 29, 1649. But Royalist resistance did not die with the king, and the fledgling Commonwealth of England was rightly concerned about his son and heir, Charles Stuart, raising an army against them. Parliament’s attention then turned to stamping out Royalist support in Scotland and Ireland.

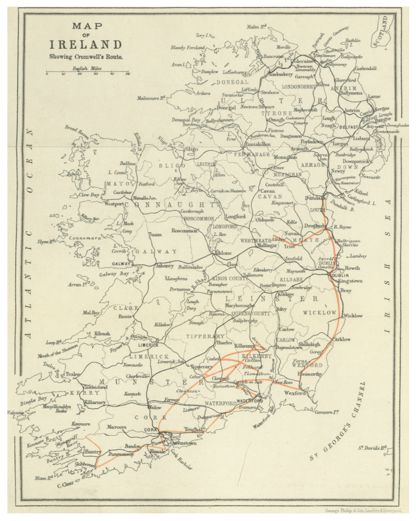

On August 15, 1649, Parliament’s commander-in-chief, Oliver Cromwell, landed in Dublin with a flotilla of approximately one hundred ships. Cromwell very quickly gained a ruthless reputation by how he dealt with Irish resistance, particularly at Drogheda, where the defenders were put to death after rejecting terms for surrender. The horror of this served him well, as many towns opted to accept his terms for surrender rather than face the possibility of massacre.

Initially, the Irish launched a centralized and coordinated defence, directed by the Royalist Marquess of Ormond. After a series of defeats, Ormond withdrew from Ireland and headed for the Continent, abandoning the splintered Irish forces.

One would expect that the Irish resistance would soon crumble, but if anything, it intensified their determination to repel the invaders. Rather than capitulating, the centralized war effort was replaced by localised fighting brigades employing guerrilla tactics. These brigades were called tories, from the Irish Tóraidhe, meaning or pursued men, and were aligned along traditional clan territories. In Munster, the brigades were led by Edmund O’Dwyer in Tipperary and Waterford, the Viscount Muskerry in Kerry and John Fitzpatrick in northern Tipperary.

The Irish brigades employed strike-and-run tactics to wear down the English and were quite successful at evading the enemy. They knew the landscape and used it to their advantage, such as evading their pursuers by slipping into bogs. The local populace also supported these troops with shelter and valuable information. The English took a hardline approach to any civilians caught collaborating with the brigades, and in the final months of the conflict, they passed decrees designed to cut off support to the Irish brigades. On January 13, 1652, they forced all tradespeople who were useful to them (e.g., blacksmiths and farriers) to report to the English garrisons. On February 13, 1652, they extended that to the populace in the contested areas to relocate to occupied territories by the end of February or be treated as the enemy. Markets were only to be held within a fortified town or garrison.

But the biggest threat to the brigades was simply a dwindling of supplies and provisions. Letters were sent to the exiled Charles Stuart for aid, but he was living under the largesse of his cousin, the French king, and France was not eager to make an enemy of the new Commonwealth. Irish leaders were communicating with the Duke of Lorraine, urging him for the twenty ships he promised, loaded with much-needed war supplies.

On January 28, 1652, only four ships arrived. One ship landed at the Aran Islands and three more arrived at Inisbofin. The total supplies included £20,000 (less £6000 for the cost of negotiation), a thousand muskets, thirty barrels of coarse powder, and a thousand barrels of rye, most of which had been spoiled by seawater.

It must have been very clear to the Irish leaders that they would not be in a position to continue their resistance beyond the spring.

The armed conflict came to an end in mid-1652, when the brigades negotiated treaties with the Parliamentary forces. Unfortunately, they Irish commanders negotiated their own treaties with the English, instead of banding together to get the best terms for everyone. The first one to surrender was John Fitzpatrick, whose forces had been destroyed and scattered months earlier, followed by Edmund O’Dwyer who came to terms in March 1652. Muskerry had been one of the last to come to an agreement, and he negotiated hard to keep control of his lands.

After the treaties were signed, the English encouraged the disbanded Irish troops to go to the Continent to fight for Spain. Mercenaries were a valuable commodity, not just for Spain, and provided they did not fight against England, their flight furthered English interests. With Irish troops leaving for the continent, that meant fewer troops could potentially rise up against the occupying forces. Irish commanders also benefited by raising mercenary forces as this represented a source of income from the foreign government. Thousands of trained Irish soldiers, referred to in history as the Wild Geese, flowed across the sea to the Continent, leaving Ireland and their people behind to deal with the occupying English. With their flight, a new heartbreaking chapter of Irish history started with extensive land confiscations and thousands being transported to the West Indies as indentured servants.

Universal Amazon Links: http://mybook.to/RebelsKnot

Universal Link: https://books2read.com/RebelsKnot

Meet Cryssa Bazos

Cryssa Bazos is an award-winning historical fiction author and a seventeenth century enthusiast. Her debut novel, Traitor’s Knot is the Medalist winner of the 2017 New Apple Award for Historical Fiction, a finalist for the 2018 EPIC eBook Awards for Historical Romance. Her second novel, Severed Knot, is a B.R.A.G Medallion Honoree and a finalist for the 2019 Chaucer Award. A forthcoming third book in the standalone series, Rebel’s Knot, was published November 2021.

Connect with Cryssa

Website: https://cryssabazos.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CryssaBazos

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/cbazos/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/cryssabazos/

BookBub: https://www.bookbub.com/profile/cryssa-bazos?list=about

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/-/e/B072871QB3

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/35489304-traitor-s-knot

Thank you for hosting me today