A slave without a past. A master without a future. A journey of discovery that will forever change the lives of both men. The ancient world comes alive in this vivid and engaging trilogy by an expert on Roman social history.

What if you suddenly discovered that you were not who you thought you were—that your true family history had been hidden from you since birth? What if the truth about your origins would cause others to despise you? What if the man who had arranged the deception was seriously ill and needed your help? What if you were a slave and that man held your life in his hands—and you his? These are some of the questions explored in the first two volumes of the new historical trilogy, A Slave’s Story.

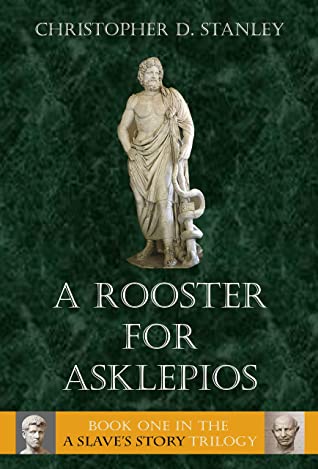

The story centers on a slave named Marcus who manages the business affairs of a wealthy Roman citizen in central Asia Minor in the first century AD. The first volume, A Rooster for Asklepios, narrates his eventful journey to a famous healing center in western Turkey following a dream in which the god Asklepios appears to promise that his master will be cured there of a nagging illness. The second volume, A Bull for Pluto, relates the aftermath of this journey. .

Along the way, both men encounter people and ideas that undermine everything that they have ever believed about themselves, one another, and the world around them. Societal norms are challenged, personal loyalties tested, and identities transformed in this engaging story that brings to life a unique corner of the Roman world that has been neglected by previous storytellers.

A Rooster for Asklepios: A Slave’s Story, Book 1 (A Slave’s Story Trilogy)

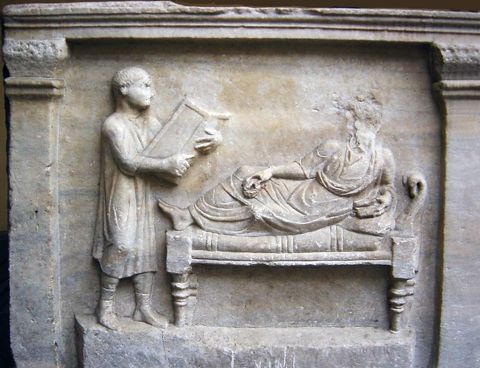

I anticipate that many of my readers will be surprised to see the relatively humane manner in which the institution of slavery is depicted in my novels, A Slave’s Story Trilogy , so I thought that I should begin this commentary with some observations about Roman slavery.

For us today, the word “slavery” conjures up a long, sordid history of native peoples being captured, sold, and abused by white colonizers who regarded them as little better than beasts of burden or intelligent tools. Some expressions of Roman slavery were every bit as bad as their modern counterparts, as with the slaves who labored in the mines and galleys that kept the Empire running. Slaves who belonged to poorer households often had trouble getting their basic needs met. Slaves at all levels of society could be beaten and abused at any time and for any reason by both their owners and anyone else to whom their owners granted permission.

Not all slaves, however, had it so bad. Those who worked in wealthy urban households could be assured of a place to sleep at night and enough food to eat, which was more than many poor free people could say. Those who were able to gain the favor of their master or mistress, as Marcus and Melita do in these stories, could enjoy freedoms and opportunities that were denied to other slaves.

At the top of the Roman slave pyramid were a small number of individuals like Marcus who assisted their master or mistress in managing their social, economic, and political lives. Slaves at this level frequently found opportunities to earn money of their own through tips and paid work, money that they could use to buy property, start a business, or even purchase their own freedom. Some succeeded in amassing enough money to arouse the jealousy of members of old-line Roman families after they were freed. The boorish freedman was a stock character in Roman social satire.

Household slaves who served their owners well had a good chance of being liberated by the time they reached their 30s. Freed slaves were granted the rights of citizenship, though they still owed certain duties to their former masters as long as they lived. Their children, on the other hand, bore no such responsibilities, and those who used their resources to cultivate productive relationships could gain positions of prominence in the life of their city, though they still had difficulty finding acceptance among the elites.

Even the most privileged of slaves, however, remained the property of another person from birth to death, a status that left them subject to the whims and fortunes of their owners. Some were willing to accept this limitation in exchange for the comforts that they enjoyed as trusted members of a wealthy household, but the number of freedman that are known from ancient literature suggests that most slaves, like Marcus, were eager to be free and readily accepted liberation when it was offered.

EXCERPT: PROLOGUE

Before the first rooster had finished crowing, Marcus was awake and rousing himself from his bedroll on the floor of the small, dark storeroom. He was sorry to see that Selena was no longer with him. Whether she had left him in the middle of the night or risen early to begin her daily chores was impossible to say. But it was no matter. She, like Marcus, was a slave in the household of Lucius Coelius Felix, and slaves had work to do before the master appeared for the morning ritual. He would see her later.

Marcus pulled his tunic over his head, then looked around for the piece of rope that he used as a belt. It was nowhere to be found. It was hard to imagine where he could have lost it—the room was bare except for a few tall pottery jars that held grain and other dried foods. Perhaps Selena had picked it up by mistake or was playing some sort of game with him. But he had no time to look for it; he had to go and prepare the family shrine for the greeting of the household gods. His master insisted that the ritual begin at the first light of dawn, before he had taken any food or drink, and it was Marcus’s job to ensure that everything was ready on time.

Marcus left his room and paced hurriedly through the darkened hallways where other slaves were beginning to stir. He passed by the kitchen, where several women were already at work in the flickering light of the hearth-fire organizing the day’s meals. Besides the family, there were fifteen adult slaves and several children who had to eat, not to mention the group of friends whom the master had invited to dine with him that evening. The guest list was small but selective, as was typical for Lucius, and it would take three women all day to prepare the delicacies that such an event demanded.

Unlike the cooks, Marcus knew exactly who would be attending. As the personal assistant to a wealthy aristocrat, it was his business to know such things. There was nothing special about the dinner—just a few of the master’s favored clients whom he wished to reward for performing various services for him in the last few months. Marcus knew that his master was not particularly fond of such dinners, but they were the grease that kept the wheels of an elite Roman household running smoothly.

The family shrine stood on the south wall of the cavernous atrium of the house, flanked on either side by small fluted columns and overshadowed by a triangular pediment that gave it the appearance of a small temple. In the recessed area between the columns, a mural depicted two Lares—household deities who guarded the family’s prosperity—dancing joyfully on either side of a mature man tending a flaming altar who represented the genius, or male ancestral spirit, of the Coelius family. Immediately below these figures curved the slithering figure of a snake, the visible image of the invisible divine spirit that watched over the household.

A narrow platform protruded from the wall beneath the snake. On this shelf stood a set of silver and bronze statuettes depicting the Penates—the gods of the food pantry—and a handful of other deities to whom the master paid daily tribute: Jupiter, the father of the gods; Cybele, the earth mother; Fortuna, the goddess of prosperity; and Mercury, the patron deity of trade and commerce. The latter god was routinely invoked in houses such as this one where the family’s wealth had been gained by shrewd business dealings rather than being inherited from a long line of ancestors.

Stepping up to the shrine, Marcus gathered up the remains of the previous day’s offerings and the vessels that had been used in the ceremony and carried them to the kitchen. There he lit an oil lamp at the fire that had been kept burning all night in honor of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, and returned with it to the shrine. More trips were required to convey the honey cakes, offering dish, wine bowl, and other items that would be needed for the morning’s ceremony. Each item had its proper place on the small table that stood directly below the altar.

When all was ready, Marcus turned his attention to the shrine itself. The process of preparing it for the impending ritual was so routine that he could have done it in his sleep: wiping the crumbs from the offering shelf, removing the leftover ashes from the miniature altar, dusting the statues, and lighting the incense burner from the sacred lamp. He worked quickly; his master could arrive at any moment, and he insisted that everything be in order when he appeared.

While Marcus was busy with these tasks, the other slaves filtered slowly into the atrium and gathered in front of the shrine. The master would enter the room alone, as he had done every morning since the death of his wife nearly a year ago from a painful wasting disease. Whether his only son, Gaius, would join them for the ritual was impossible to say; it depended on how late he had been out carousing the previous night and who was sharing his bed this morning.

His labors finished, Marcus slipped into his usual position beside the steward Trophimus in the front rank of the waiting slaves, directly behind the spot where his master always stood. As head of the Coelius household, it was Lucius’s duty to preside as priest over the rituals and ensure that they were performed in precisely the same manner every day, as Roman custom dictated. Marcus bowed his head in a show of respect to the gods and the other slaves followed suit.

Soon the clatter of approaching sandals caught his ear. Marcus looked up to see Lucius entering the atrium accompanied by the slave girl Selena, who had been asleep in his own bed the last time he saw her. His rope belt was tied around her waist. She gave Marcus a fleeting glance, then lowered her eyes. Now he knew why she had disappeared before the morning—her services had been needed elsewhere.

Marcus could not complain, of course, since everyone knew that the bodies of household slaves were at their master’s disposal. But this was something new; never before had Lucius permitted a slave girl to accompany him to the morning ritual. Whatever the reason for the change, Marcus knew that he would have to keep his distance from Selena for the time being, at least until his master tired of her. But it mattered little; there were other women in the household who would be happy to share his bed, not to mention the ones at the local bordello.

AMAZON Link: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08B2J4XJ2

Meet Christopher Stanley

CHRISTOPHER D. STANLEY is a professor at St. Bonaventure University who studies the social and religious history of the Greco-Roman world, with special attention to early Christianity and Judaism. He has written or edited six books and dozens of professional articles on the subject and presents papers regularly at conferences around the world. The trilogy A Slave’s Story, which grew out of his historical research on first-century Asia Minor, is his first work of fiction. He is currently working on an academic book that explores healing practices in the Greco-Roman world, a subject that plays a vital role in this series.

Website: http://aslavesstory.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/aslavesstory